BUILD MANUAL

WARNING:

Manual Outline and Table of Contents is not available for smaller screen sizes.

Consider using your device in landscape mode or switching to a device with a larger screen.

What you need to start

Miscellaneous

(1) Laptop with Ubuntu Xenial 16.04.01 LTS installed. (Other versions of Ubuntu may work as well, but we can’t guarantee this.)

The Hardware Kit

Mechanical

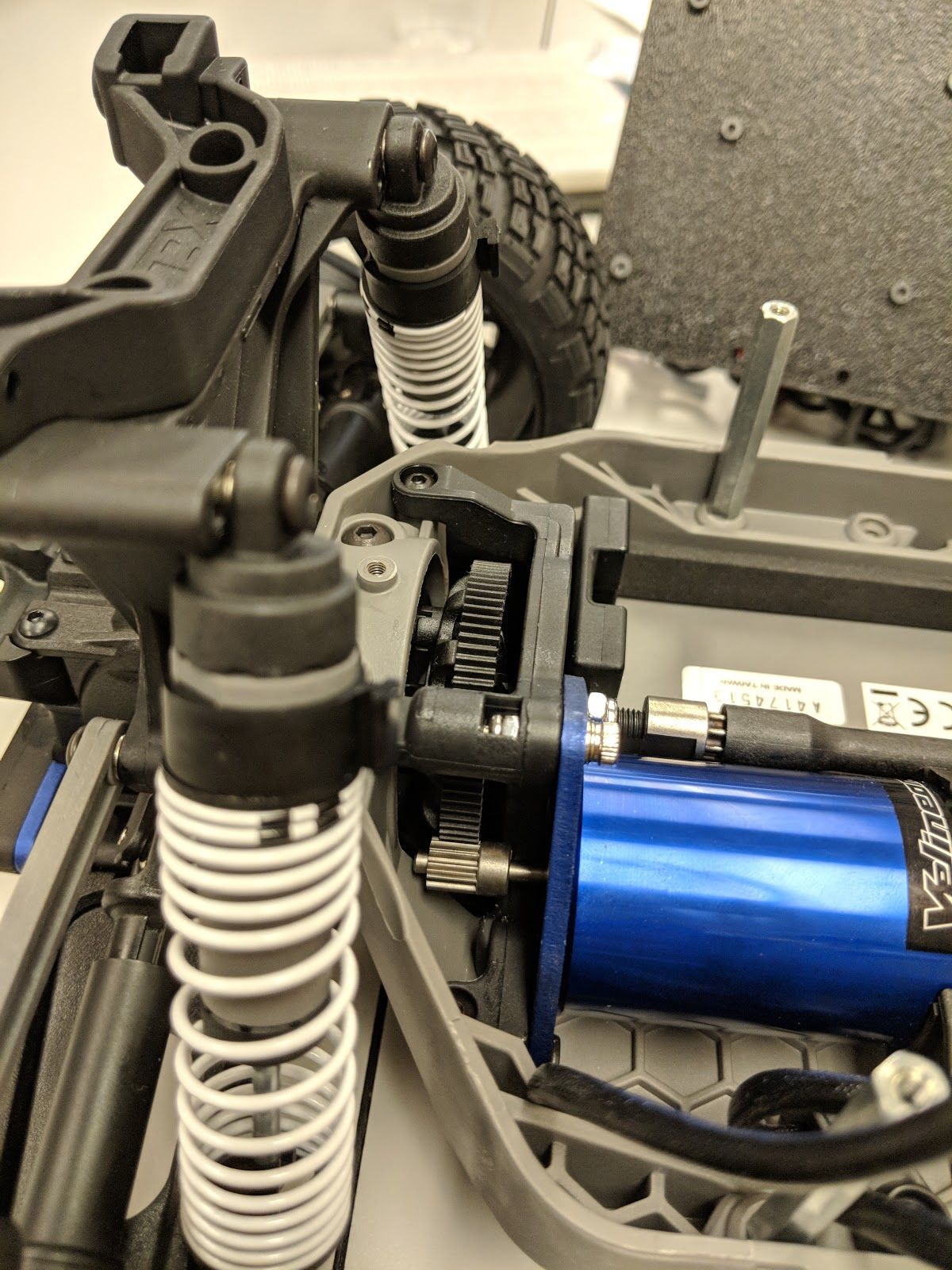

(1) Traxxas RC rally car (recommended model: Ford Fiesta ST)

Note: as of August 2018, this car is sold with a brushed motor by Traxxas. See link below for brushless motor.

(1)

Velineon 3351R/3500 brushless DC motor

(1) laser-cut chassis on which you will mount everything

(1) LIDAR mount with (2) C-shaped brackets

(2) threaded 14mm M3 standoffs

(4) 19mm M3 standoffs

(8) 35mm M3 standoffs

(4) 45mm M3 standoffs

(35) 10mm M3 screws

(4) 20mm M3 screws

(4) 8mm round nylon spacers

(1) Roll of double-sided tape (for mounting USB hubs and optionally FOCbox)

Electrical

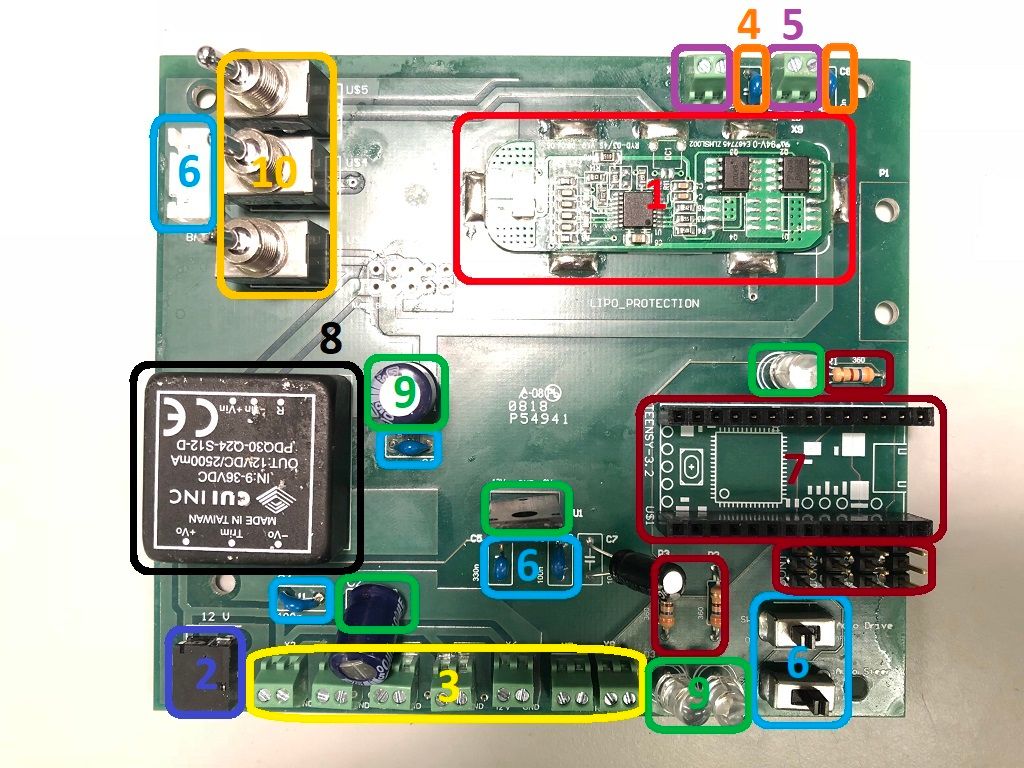

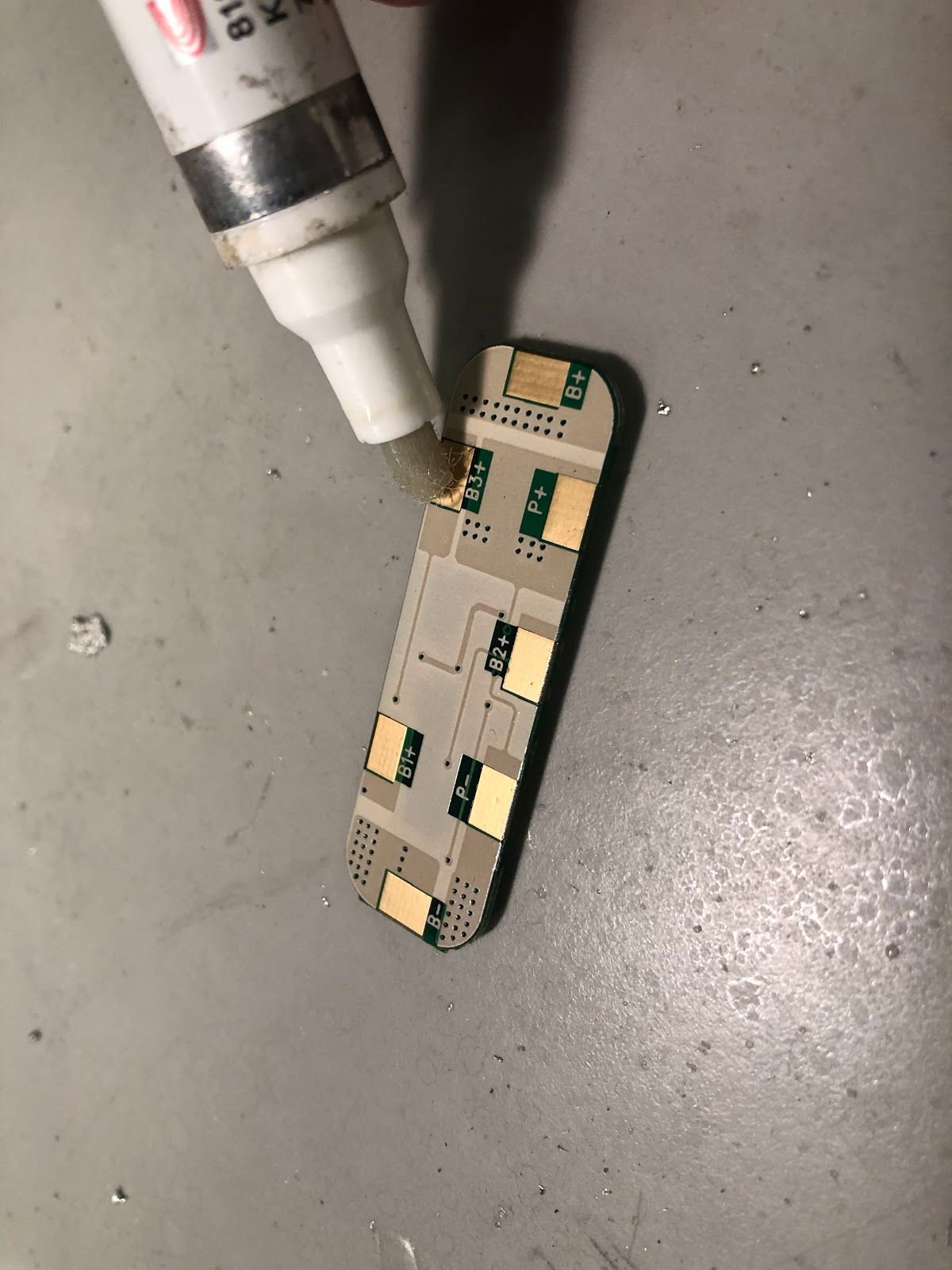

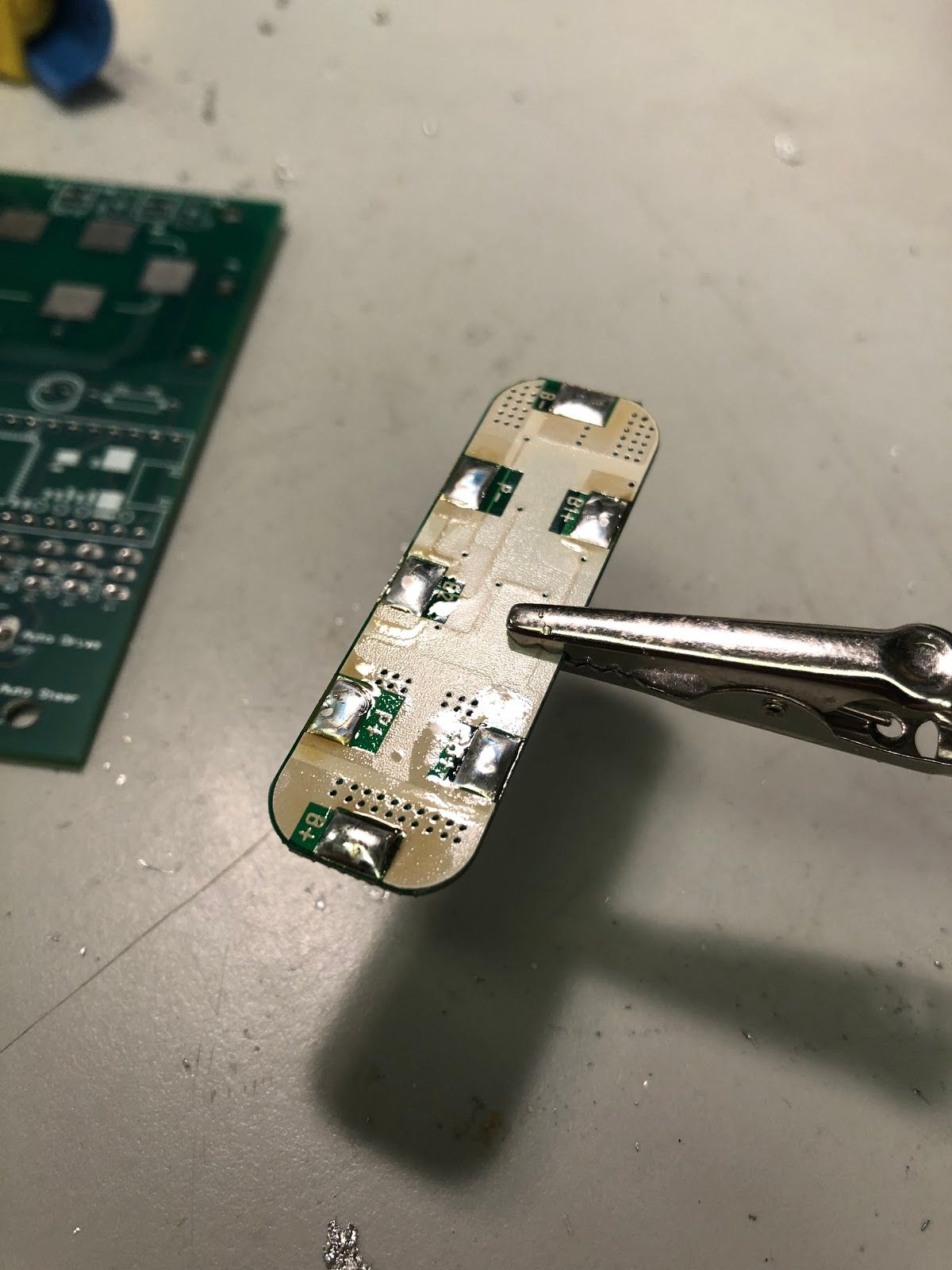

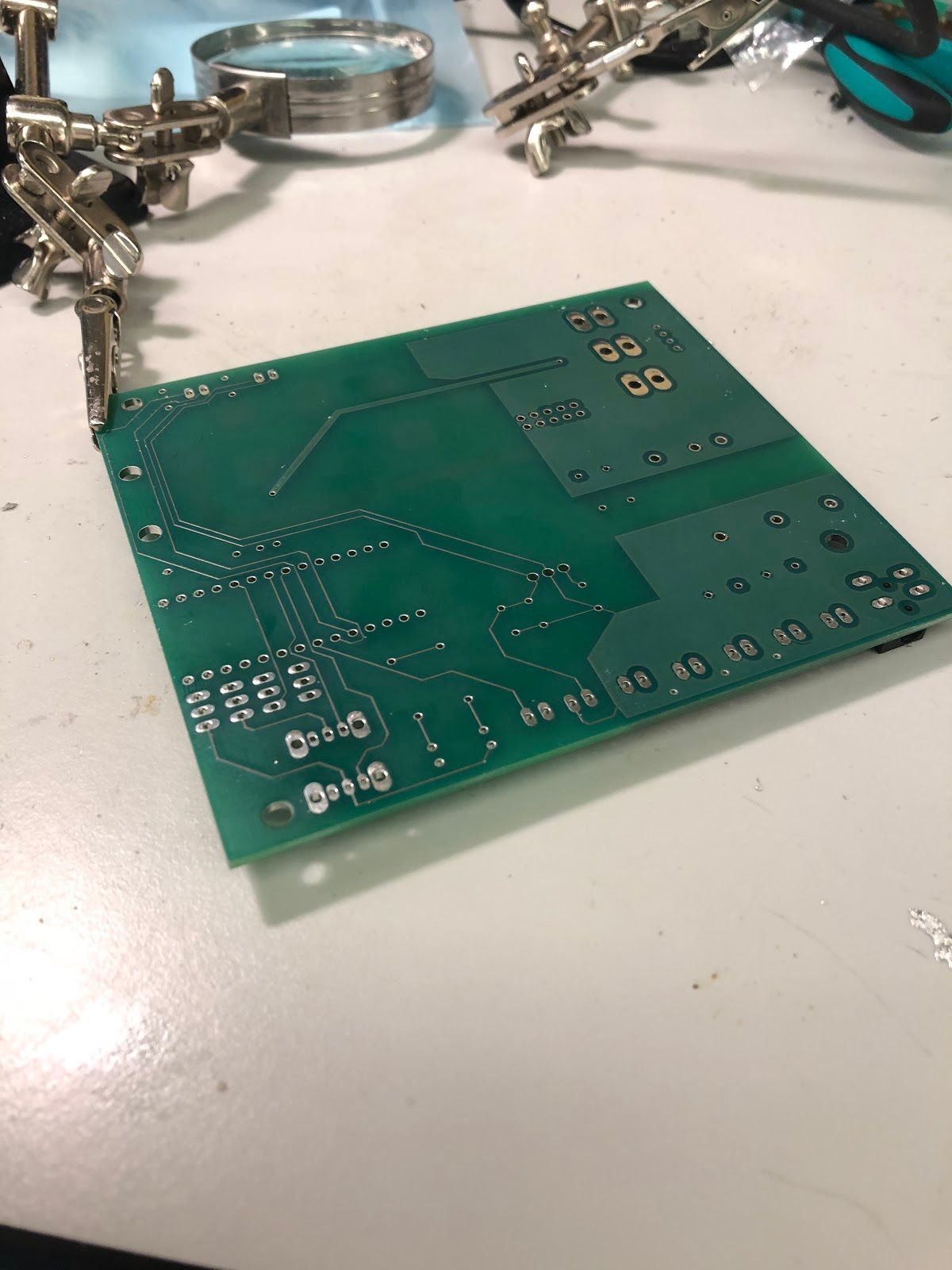

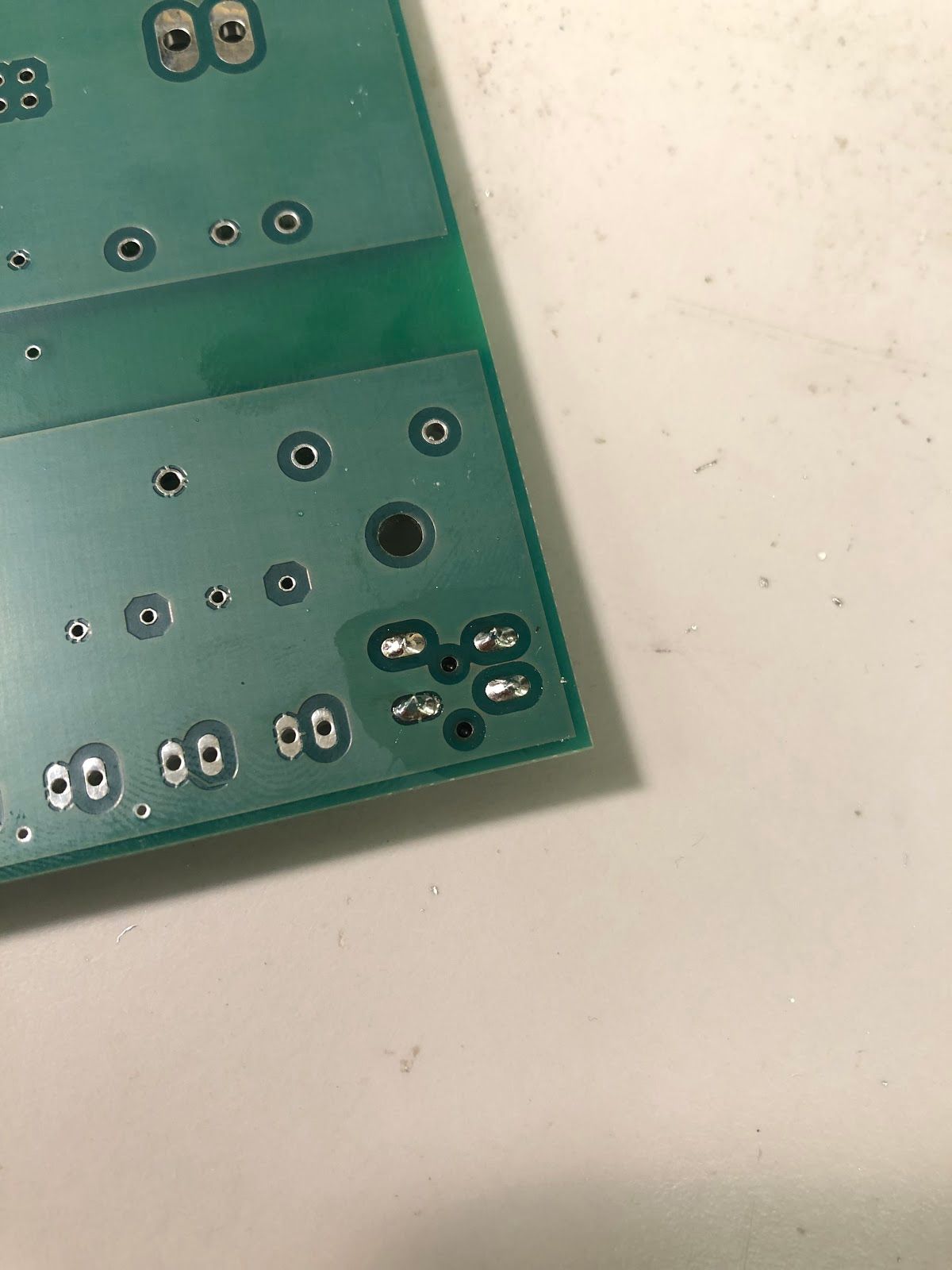

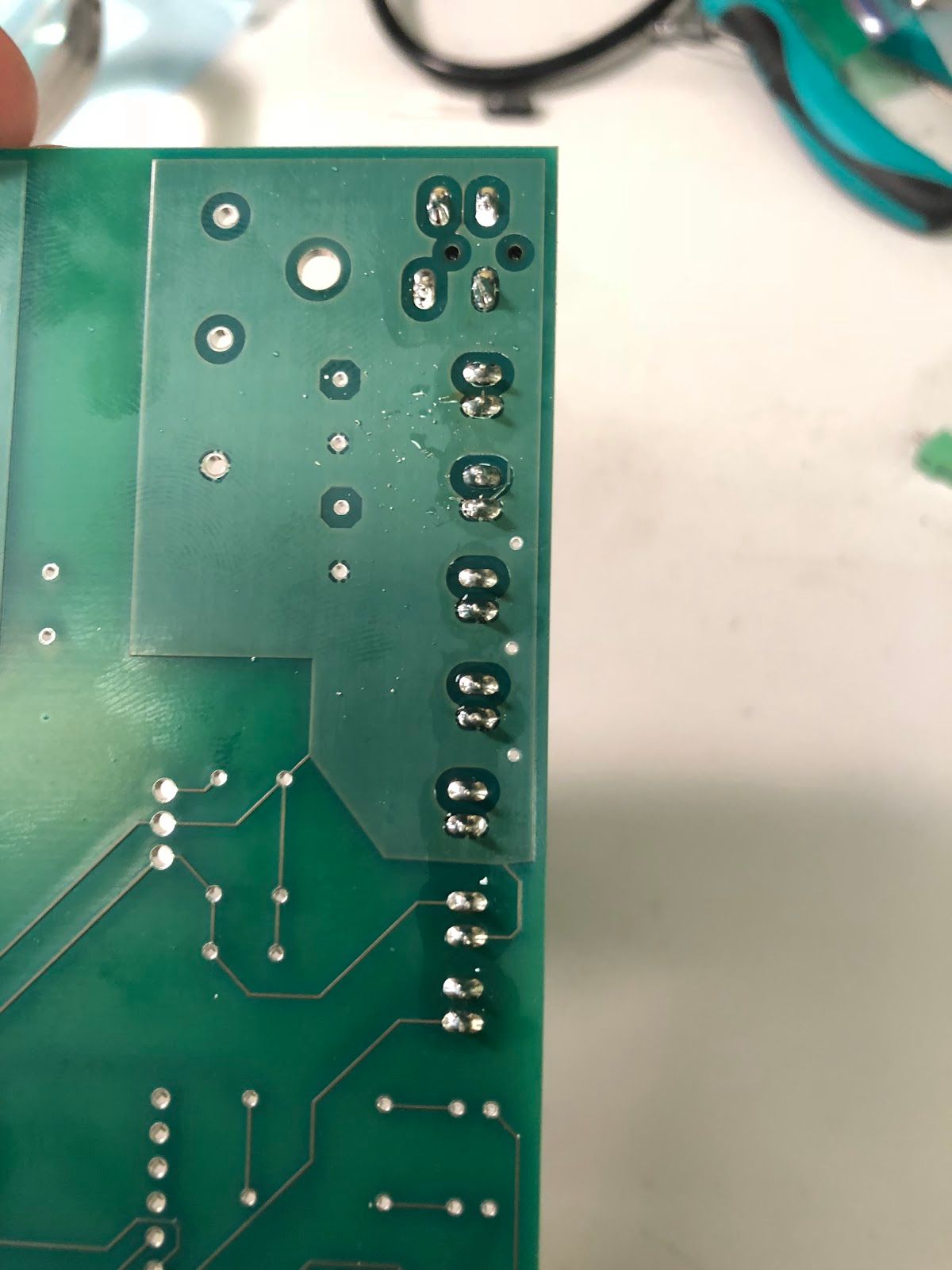

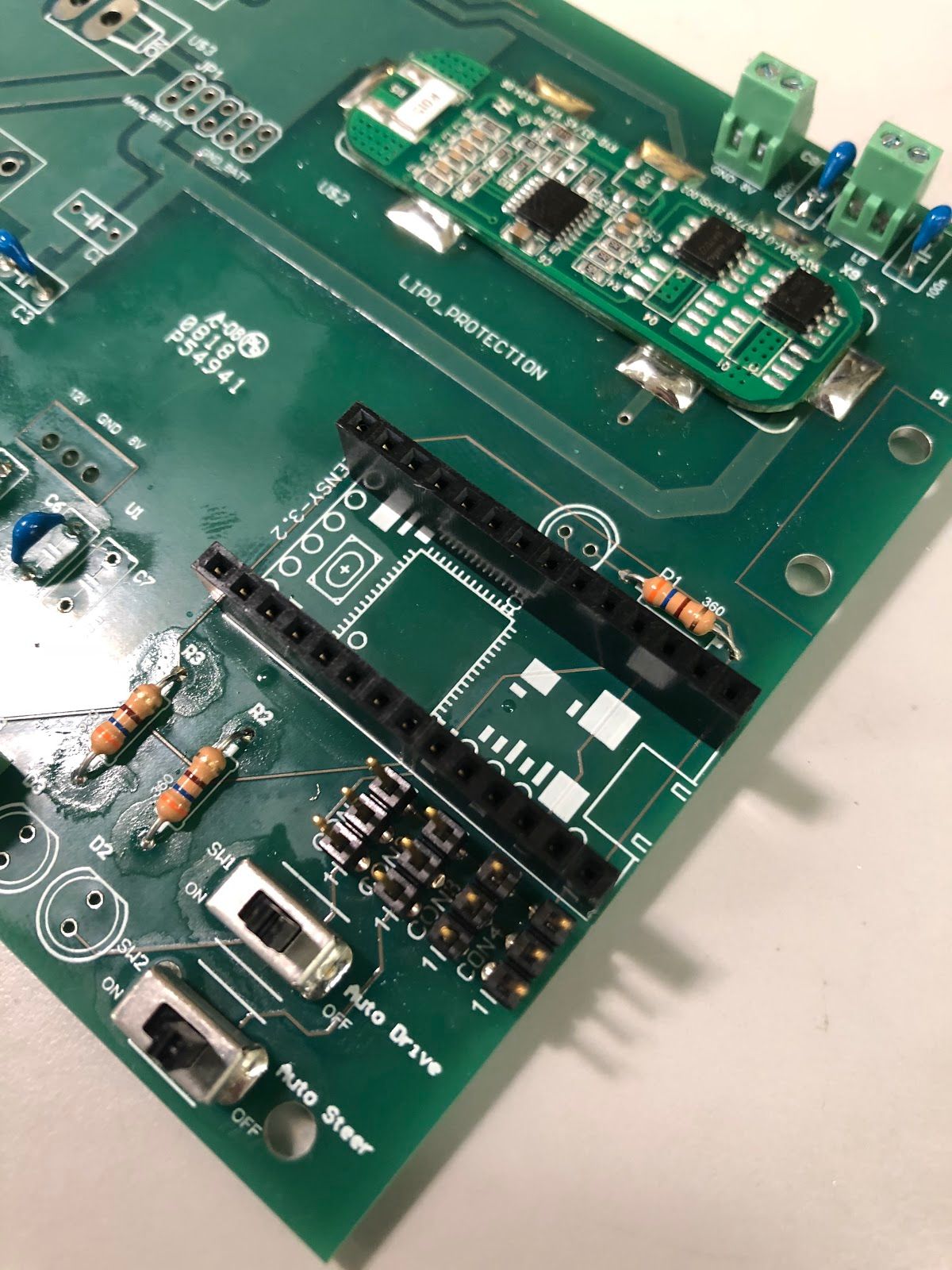

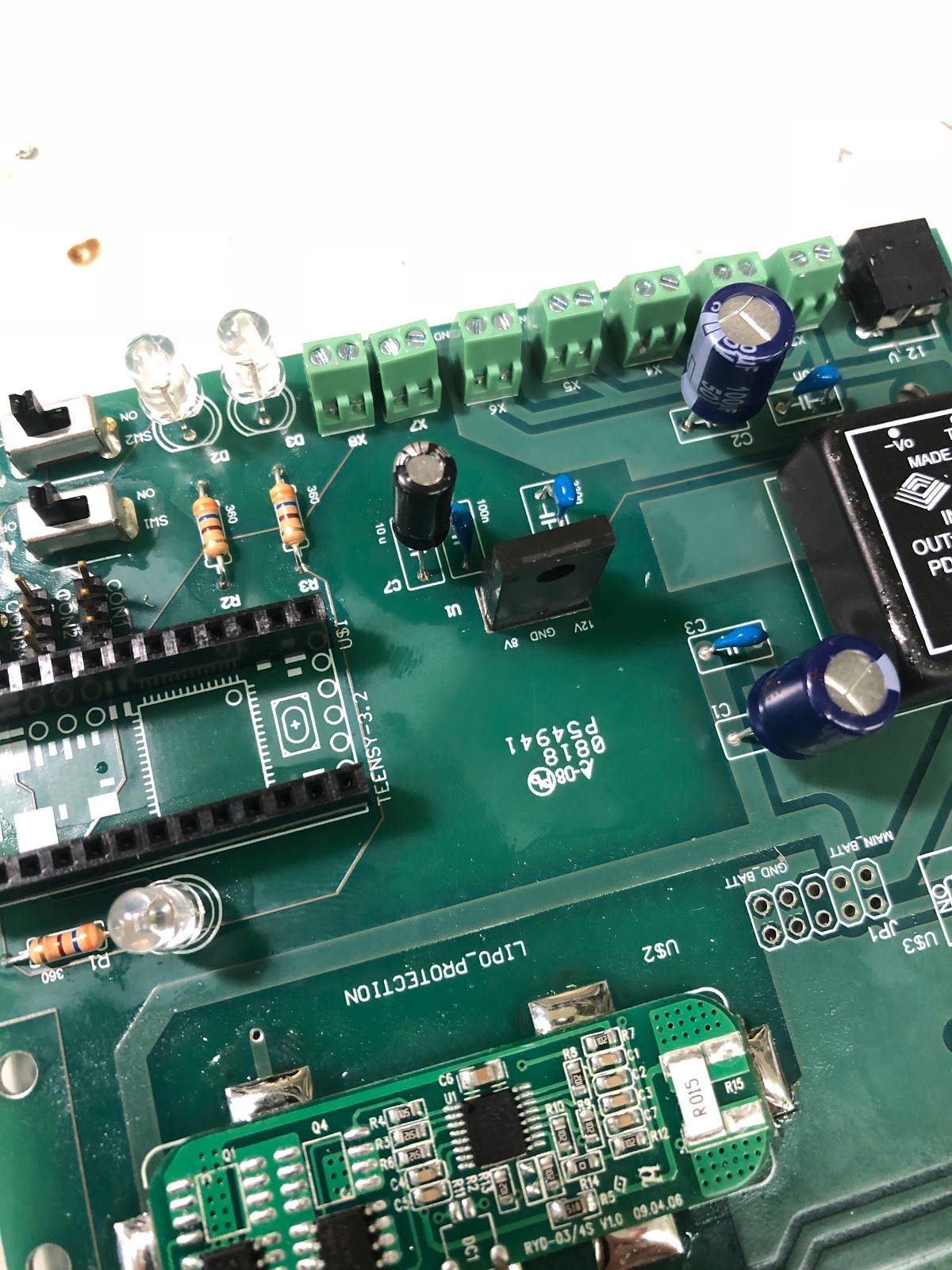

(1) power board (obtained from University of Pennsylvania team. This was designed at Penn, printed by www.4pcb.com)

(1) Nvidia Jetson TX1 or TX2 with Wi-Fi antennas (included with the development board)

(1) Orbitty carrier board (for Jetson)

(1) Hokuyo 10LX or 30LX LIDAR

(1) Traxxas LiPo or NiMH battery (at least 9V)

(1) FOCbox or VESC 4.12 electronic speed controller

(1) USB hub (at least 6 ports)

(1) short (~1 ft) USB micro cable

(2) spools/strips of 22 AWG wire of different colors (preferably red and black)

(1) USB keyboard and mouse

(1) HDMI display

Optional: (1) HDMI dummy plug and (1) USB Wi-Fi adapter for connecting to the car via VNC

Tools

(1) Metric ruler

(1) Needle-nose pliers

(1) Wire strippers

(1) 2mm width or smaller flathead screwdriver

(1) 5/64 inch diameter hex driver key or small Phillips screwdriver (1) Hex socket driver or wrench (to hold standoffs in place)

(1) T3 Torx screwdriver

Bill of Materials

Preparing and Assembling the Car

Preparing the Car

Coming Soon: will fill out when the fourth Traxxas car arrives

Obtaining the Power Board

- [Instructions on getting the power board from Penn,

- and a link to files that you would send to a PCB company like 4PCB or PCBWay. Currently on github]

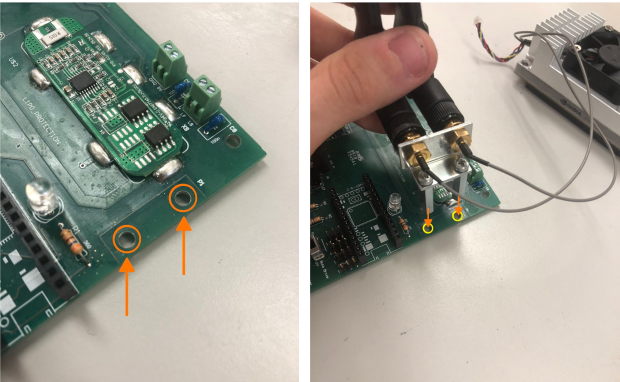

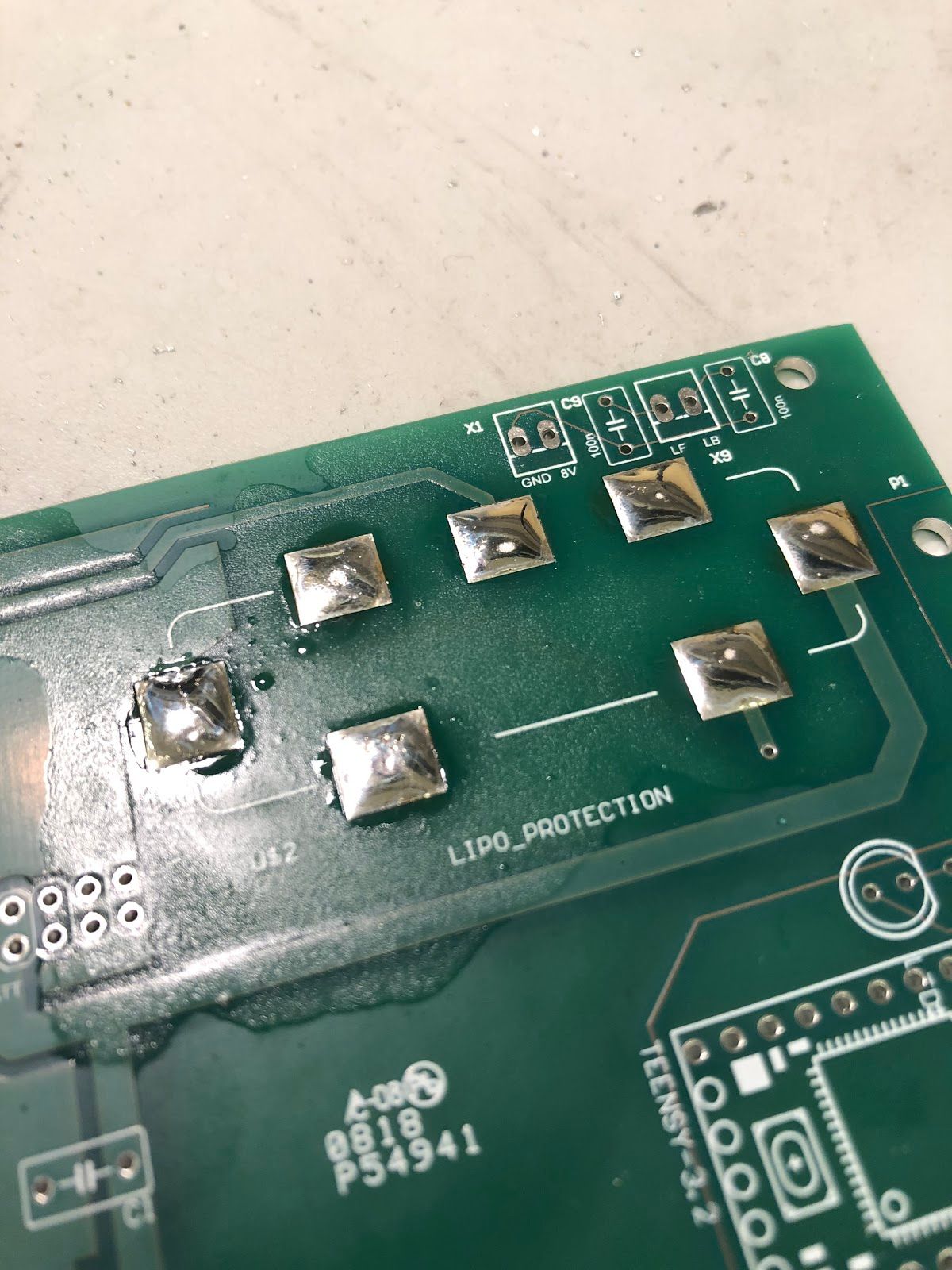

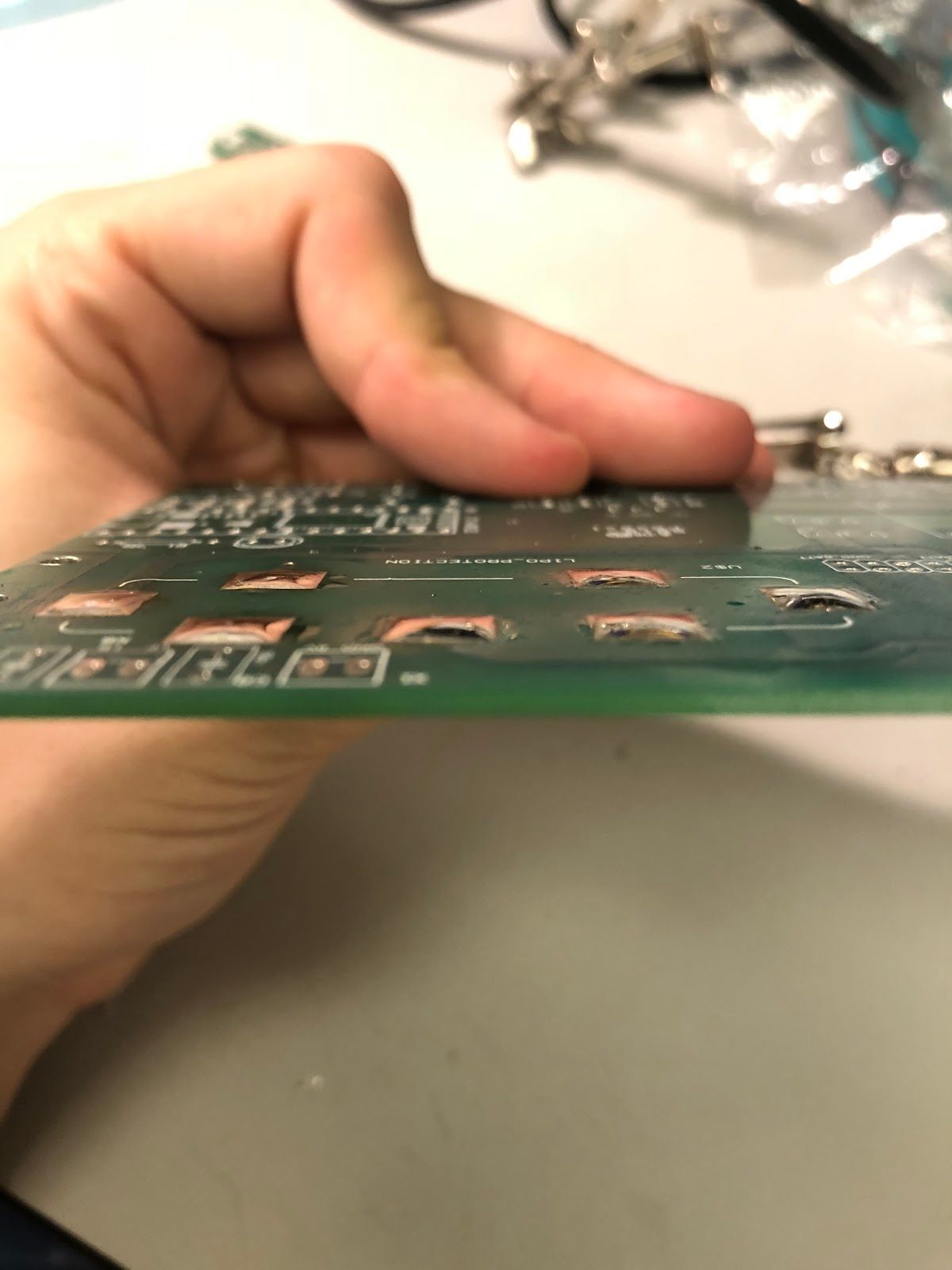

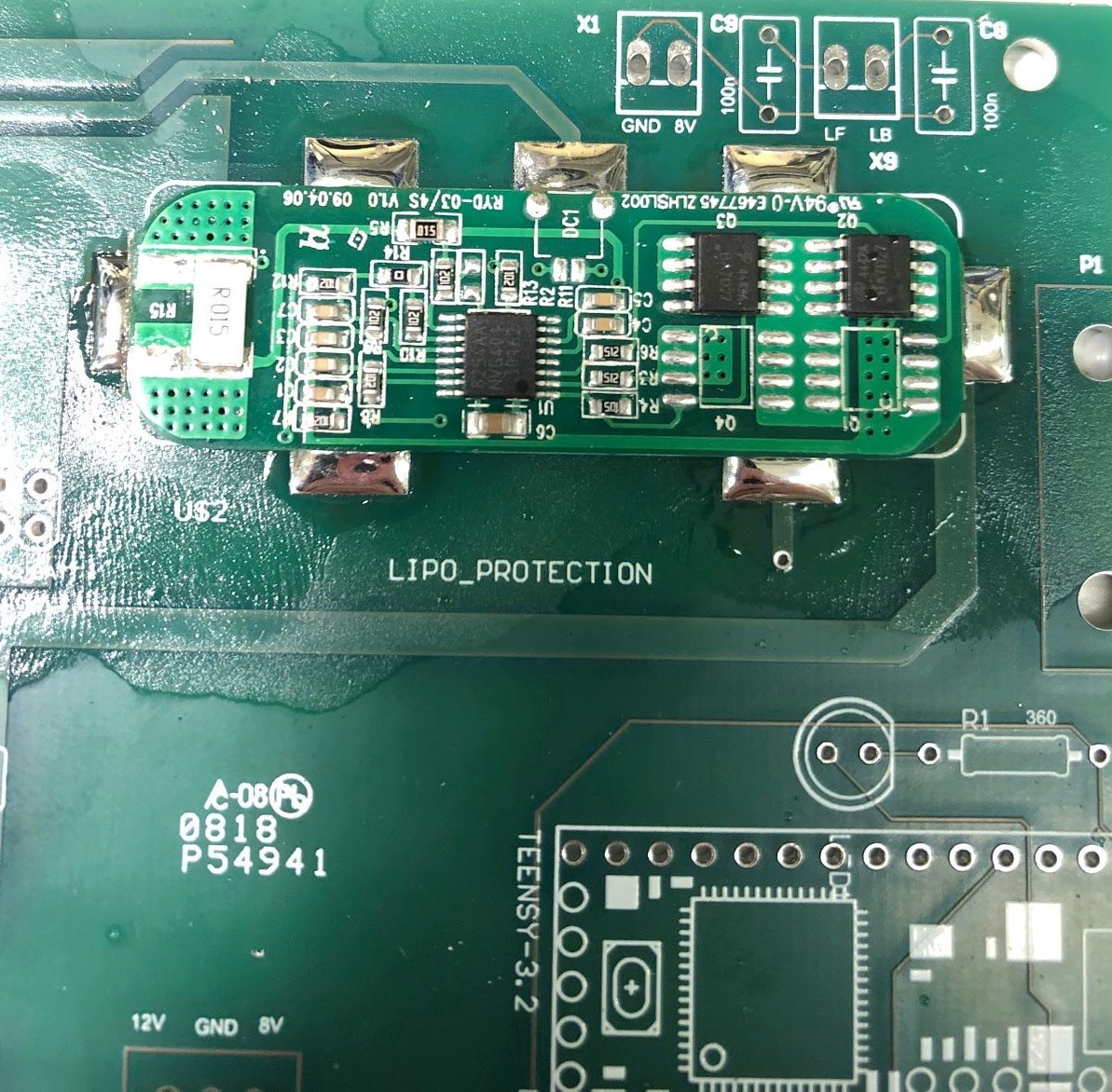

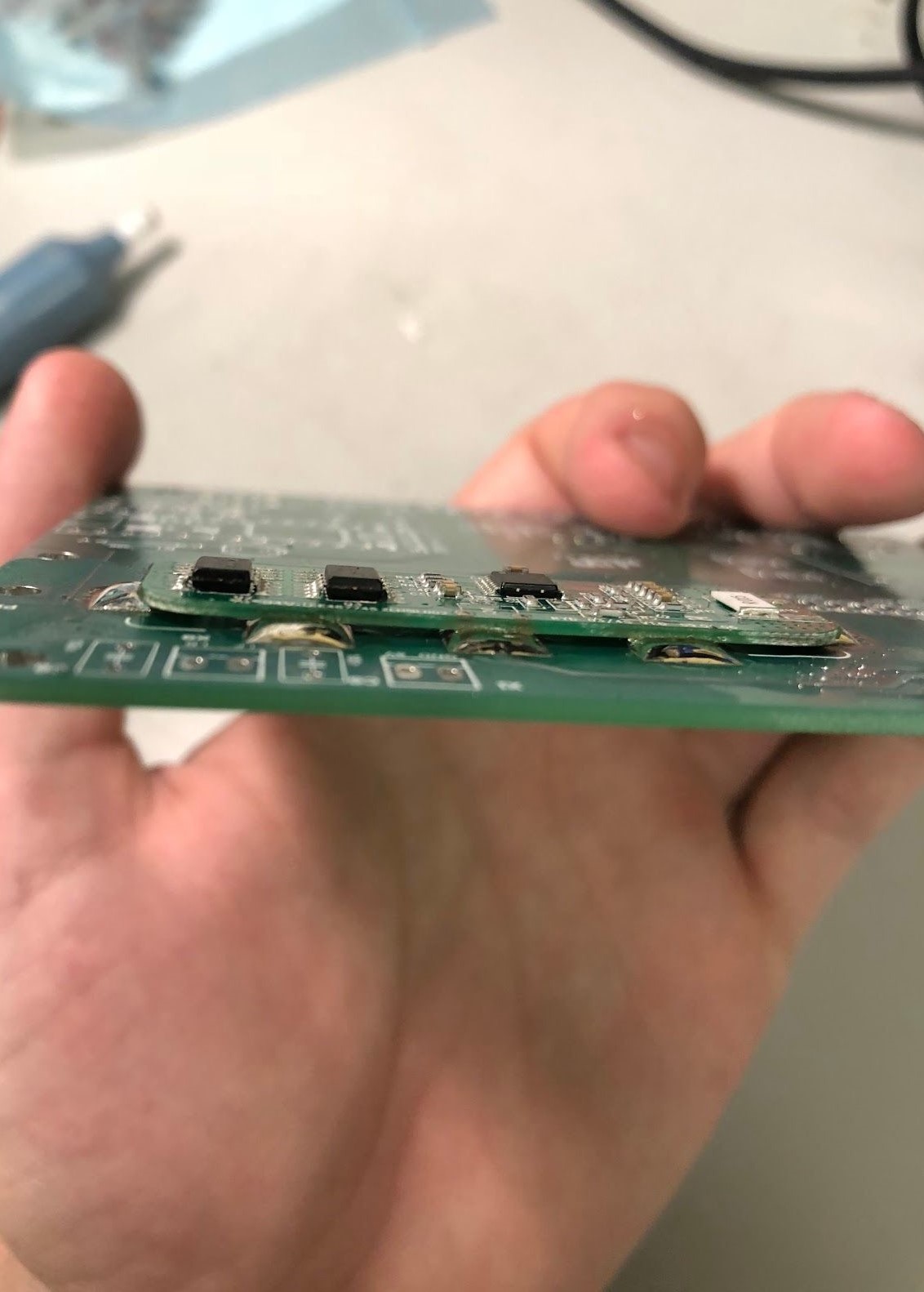

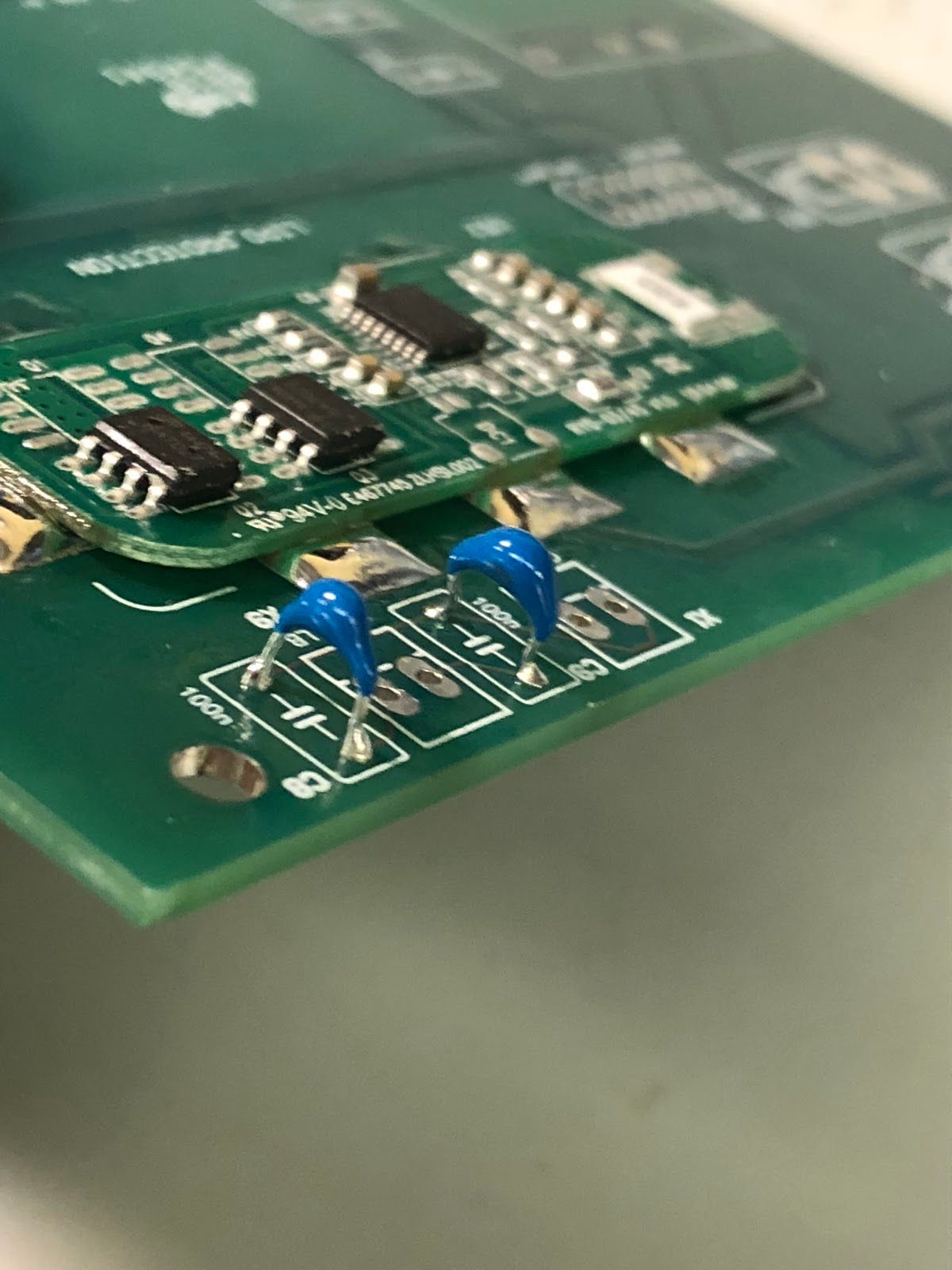

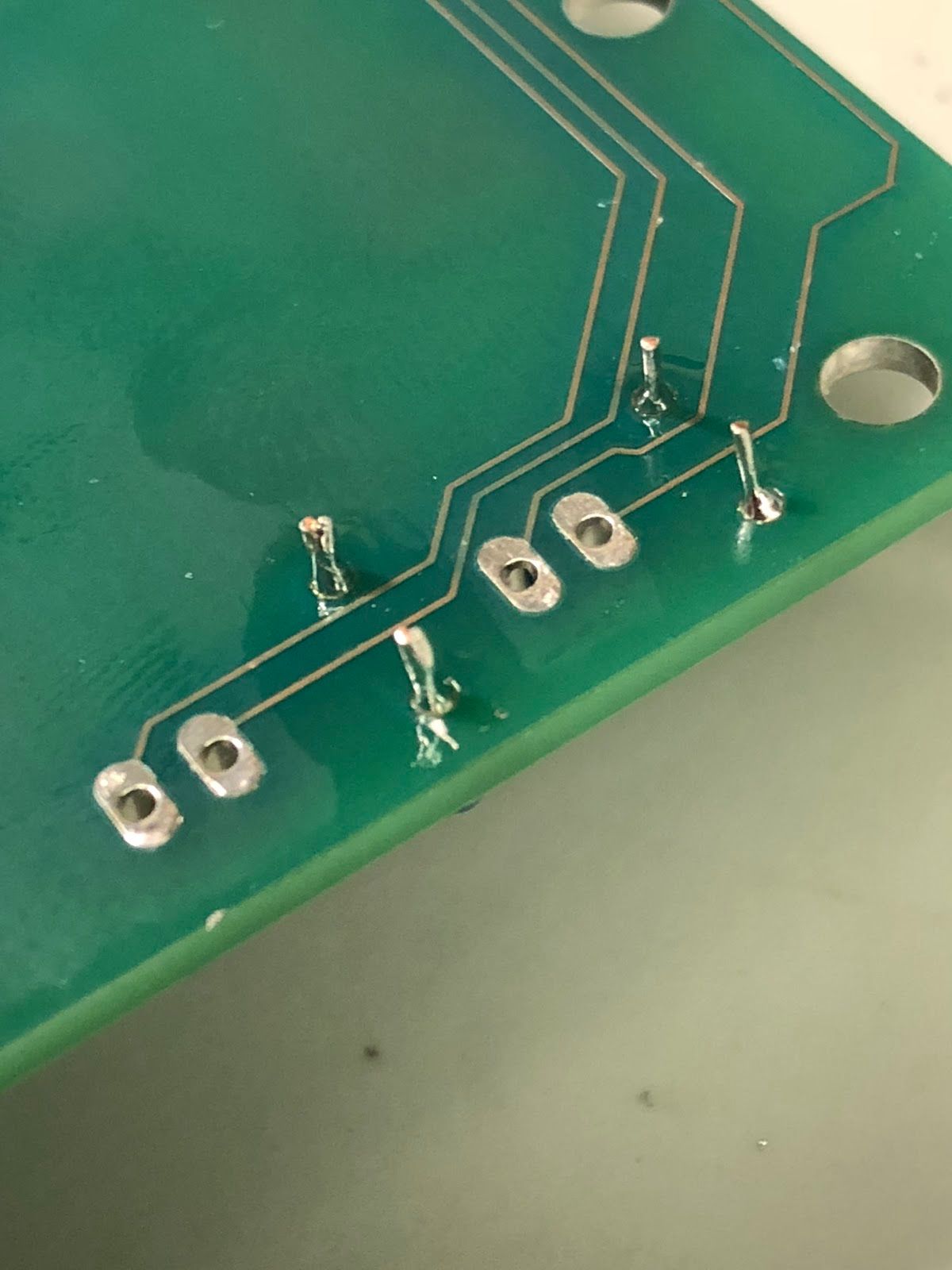

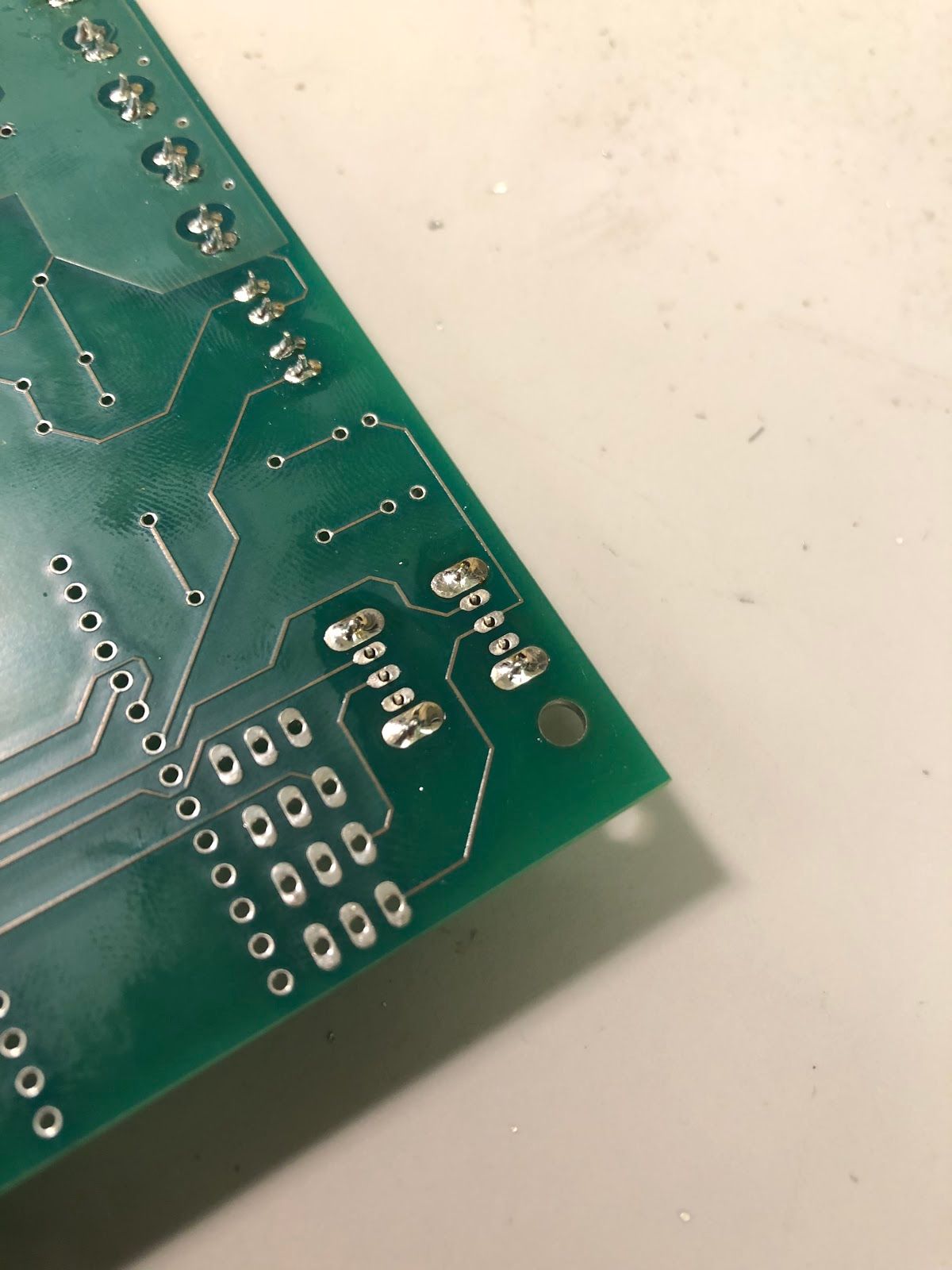

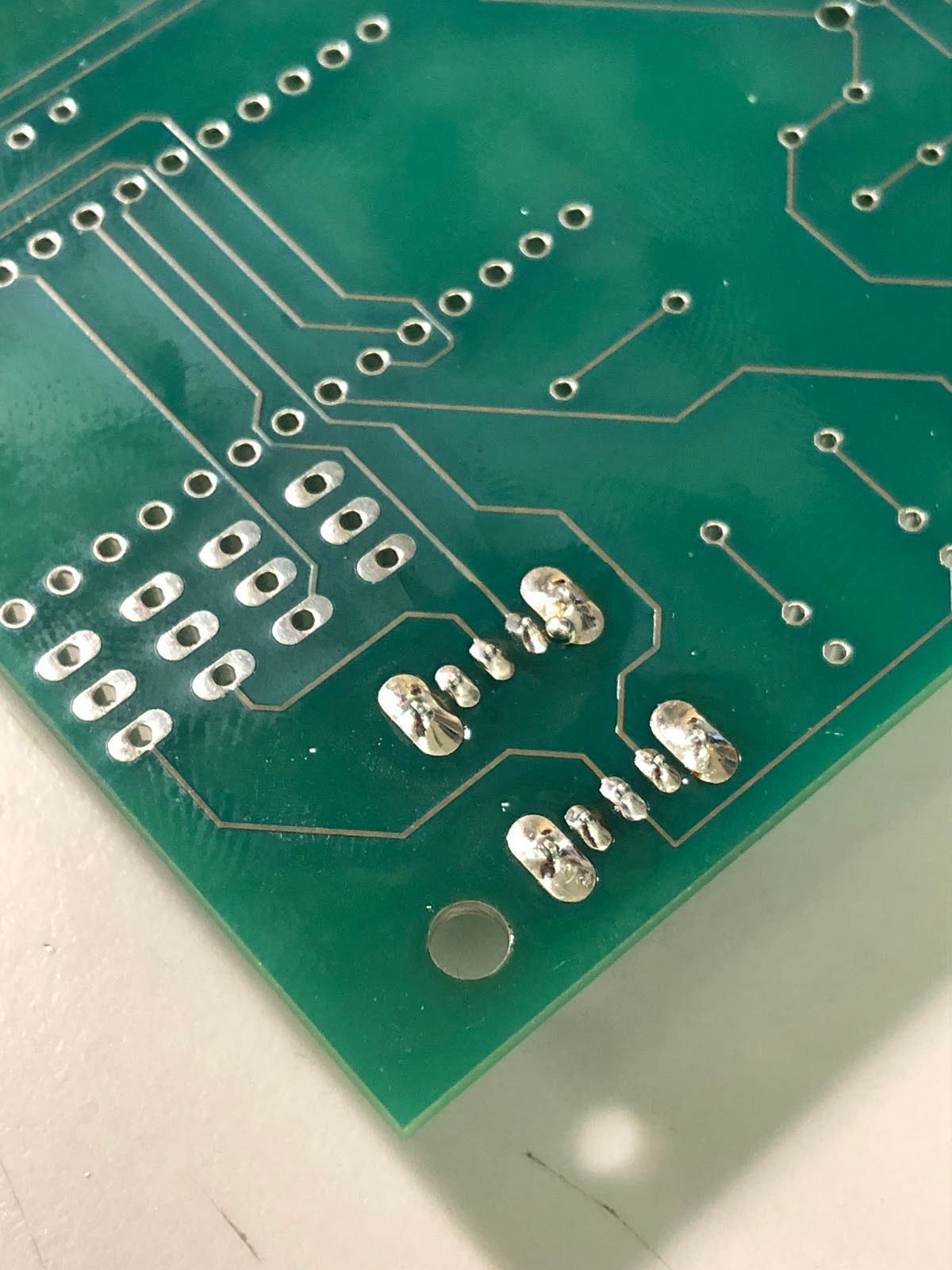

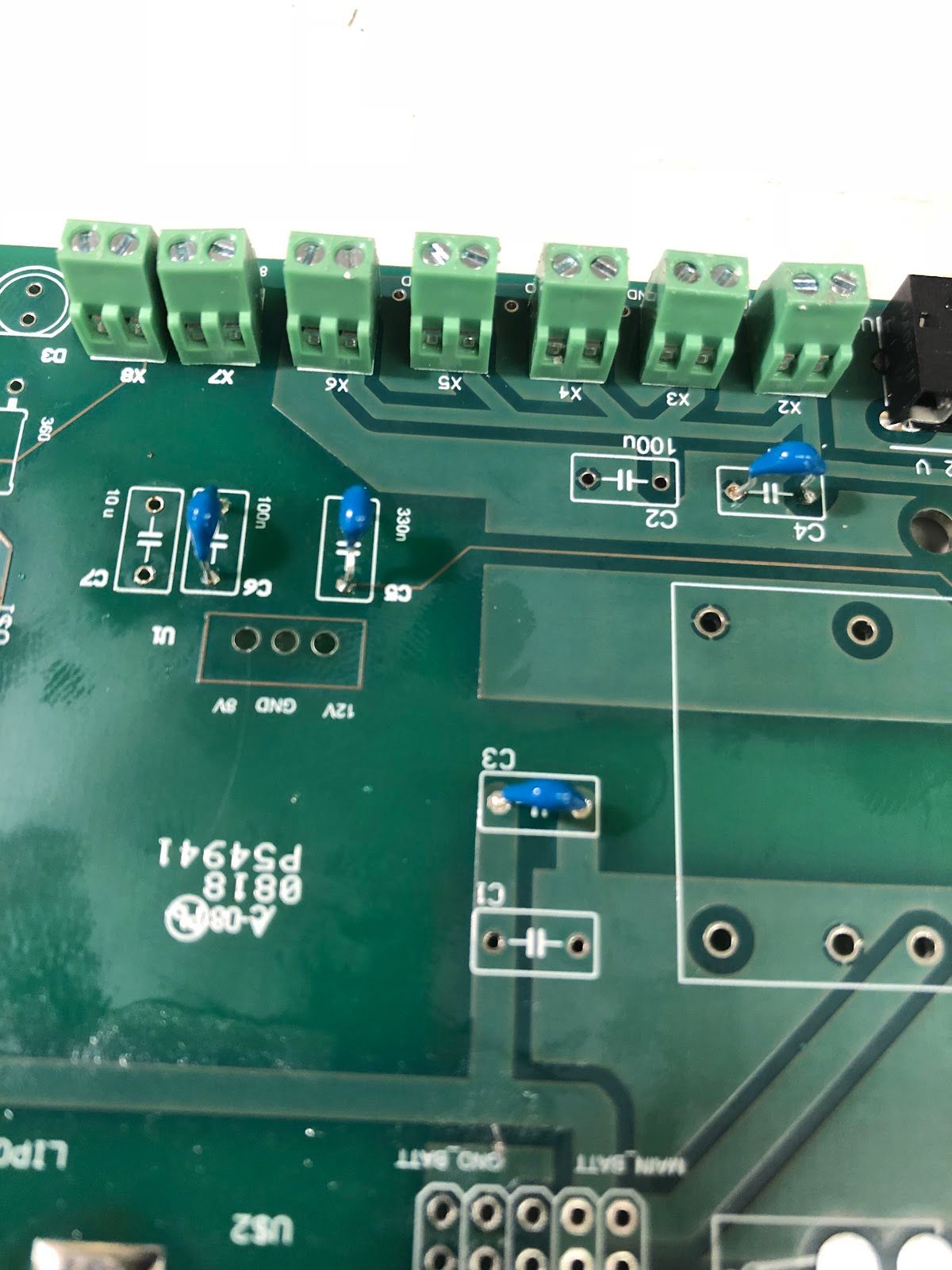

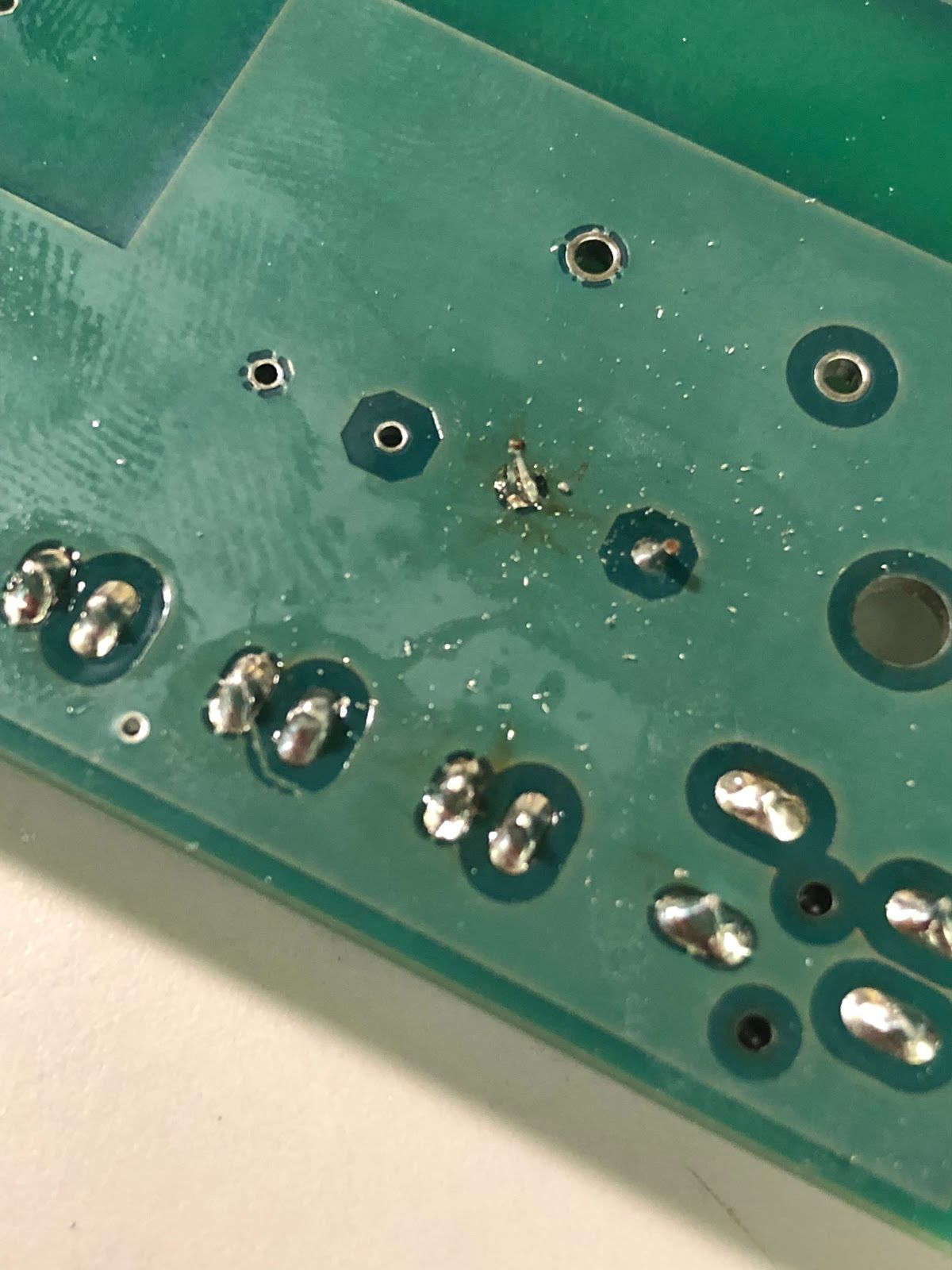

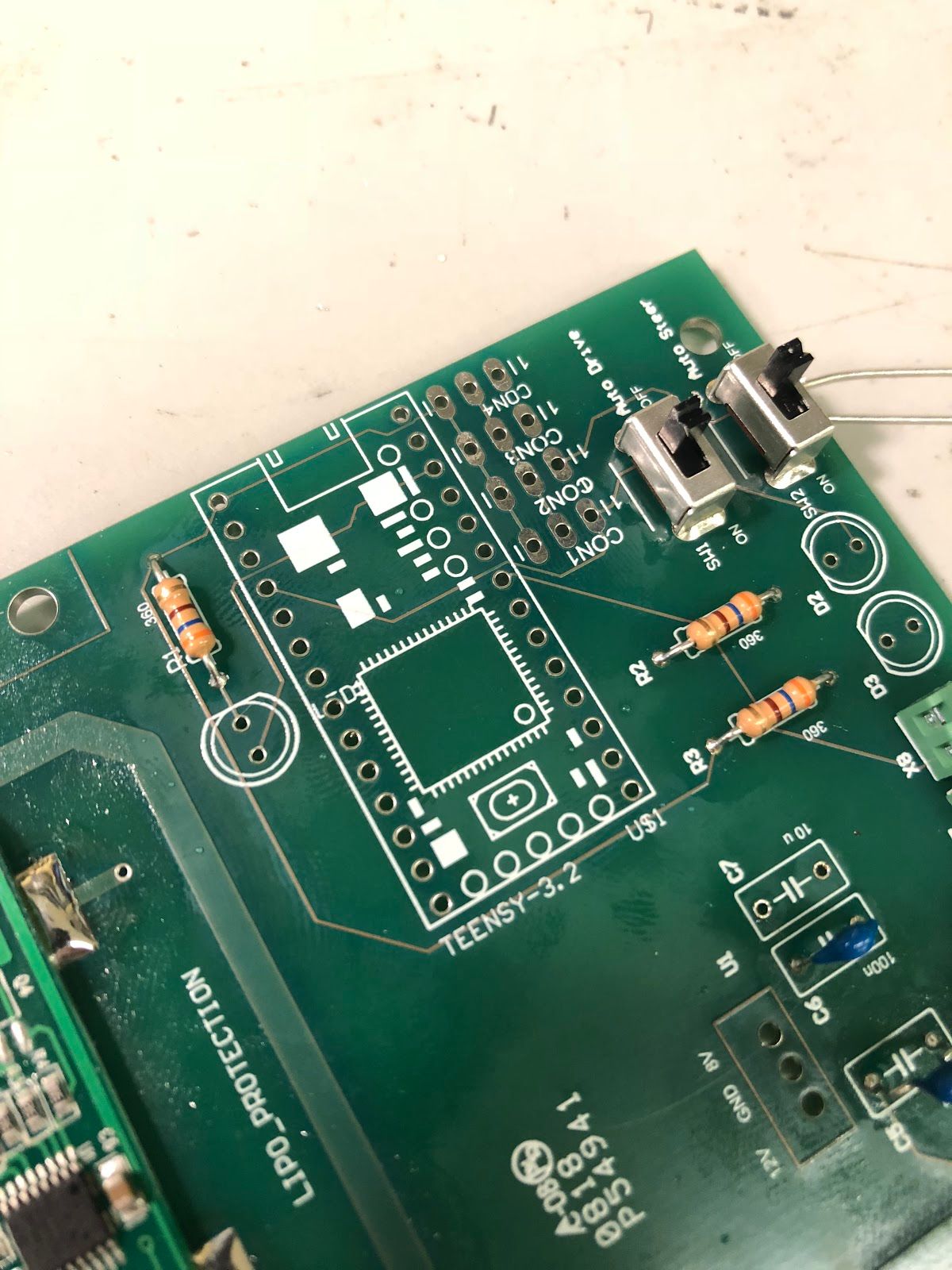

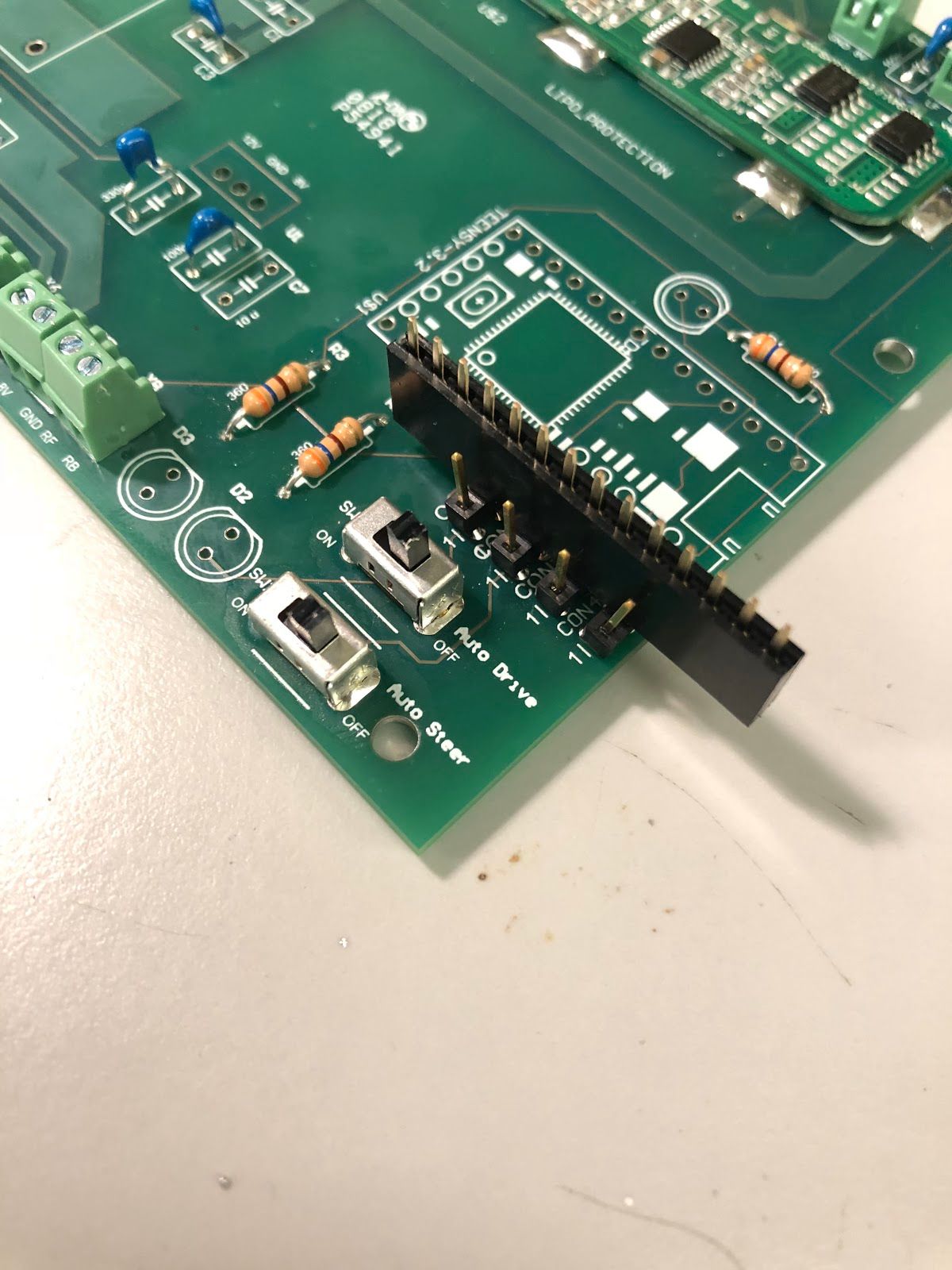

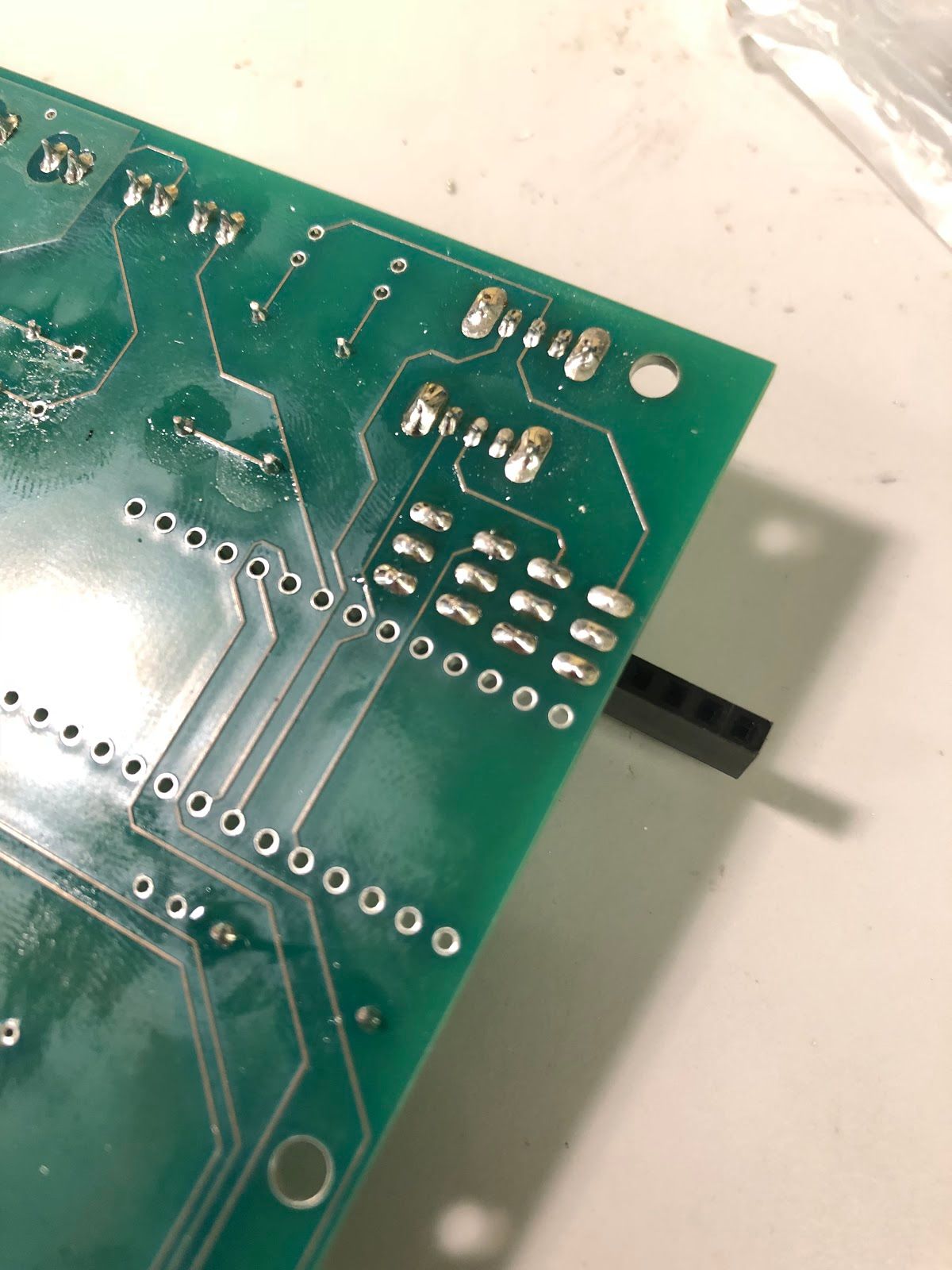

A note on why we have a power board: The power board is used to provide a stable voltage source for the car and its peripherals since the battery voltage drops as the battery runs out. The board does not do any charging of the battery, so you will need a Traxxas EZ-Peak charger to charge it (you can find them on Traxxas' website). At present, there's no way to know the battery's charge level except by measuring it with a multimeter or the BLDC Tool as it runs, but we could think about adding a low voltage LED or seven-segment LCD display (to show the voltage) to the next iteration of the board. The LIPO protection module and green connectors are currently unused and are a legacy from previous RoboRacer car iterations which used the Teensy microcontroller as a motor driver.

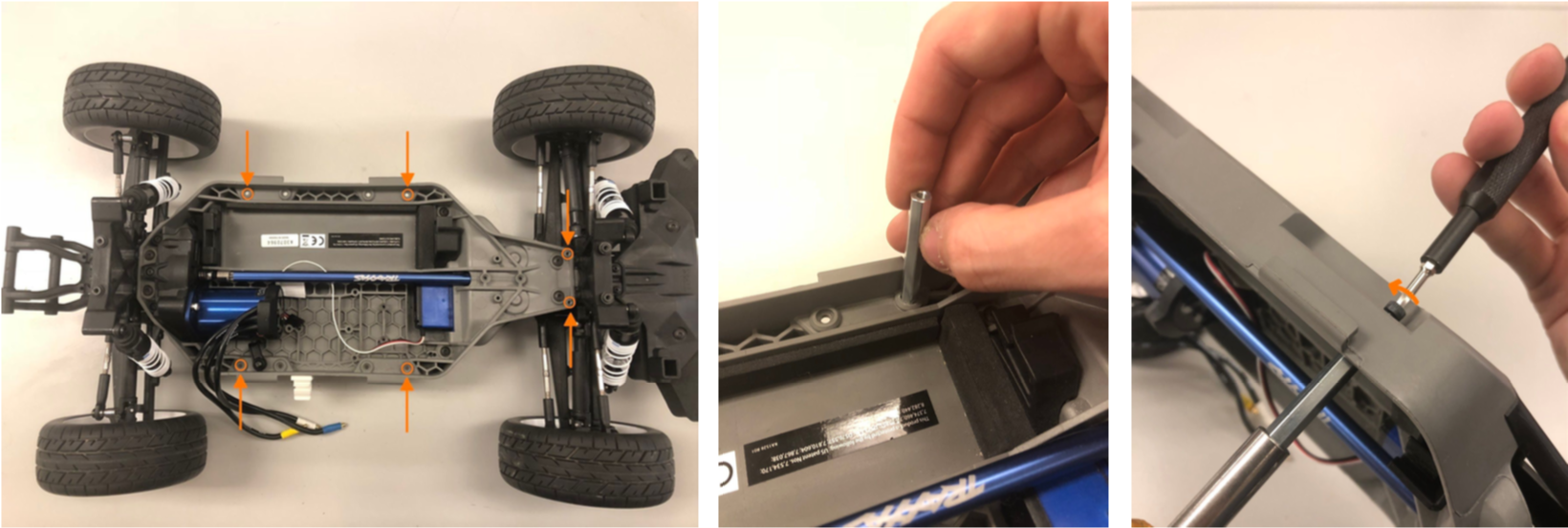

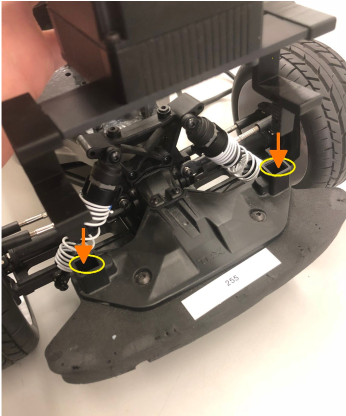

Installing the Body Standoffs

Begin by installing four 45mm M3 standoffs into the holes of the main car body pictured below. Secure the standoffs to the bottom of the car using 10mm M3 screws, and use either nosepliers or a hex driver to hold the standoff in place while you turn the screw on the other side. Pay attention to where you install the standoffs since there are several mounting holes on the car's base. See the picture below for clarification.

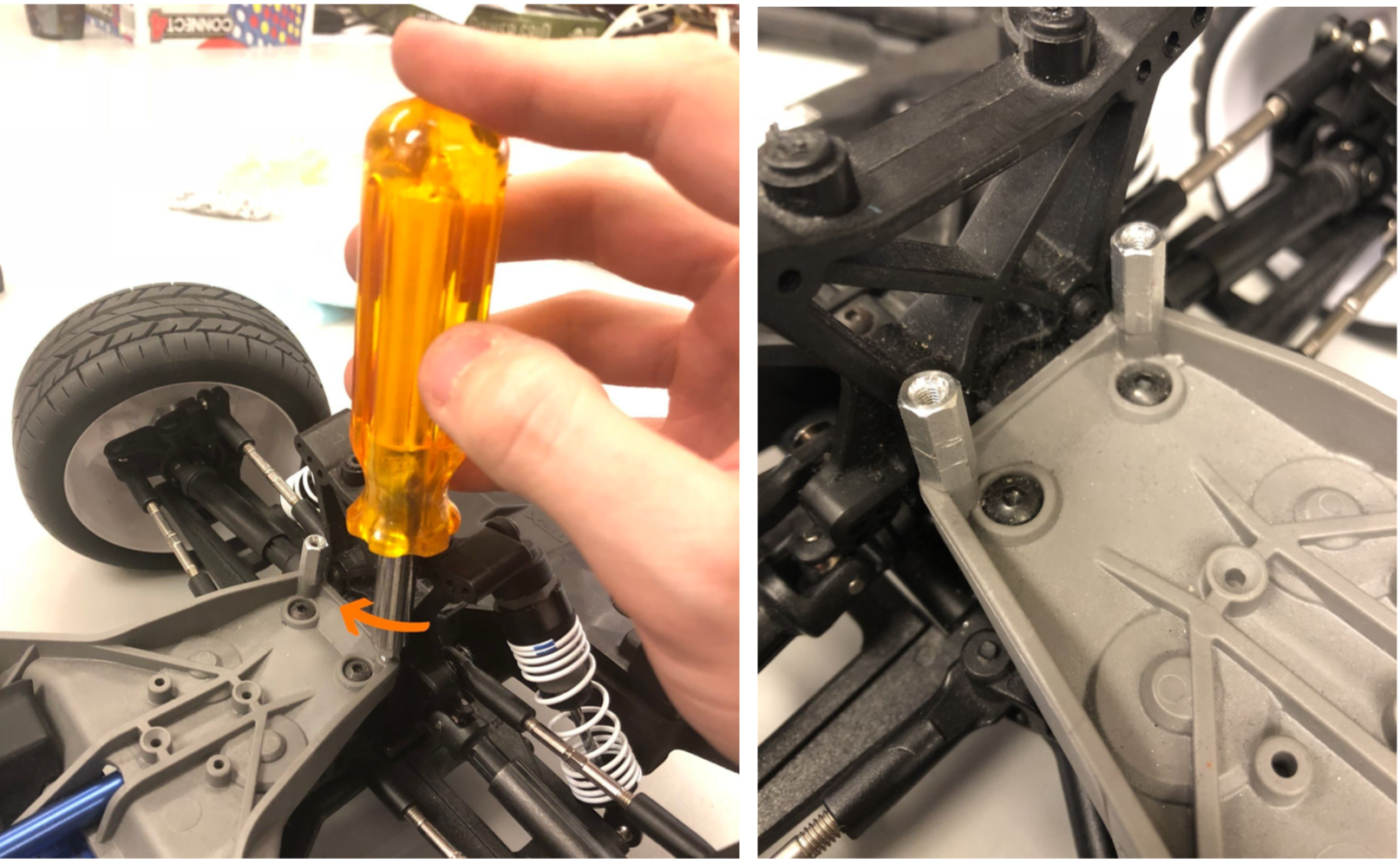

Next, install two threaded 14mm M3 standoffs into the front holes in the car base, using the pliers or hex driver to thread the standoffs into the holes. Don't mount the chassis to the car yet since we still need to mount the Jetson and power board to the chassis.

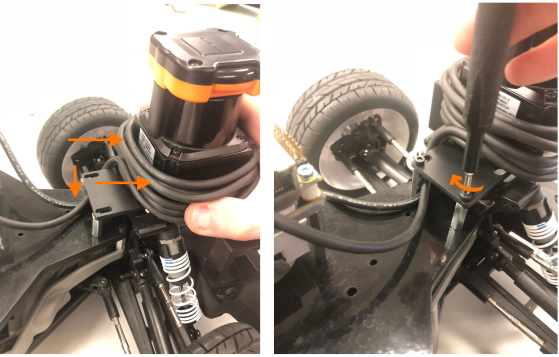

Mounting the FOCbox to the Chassis

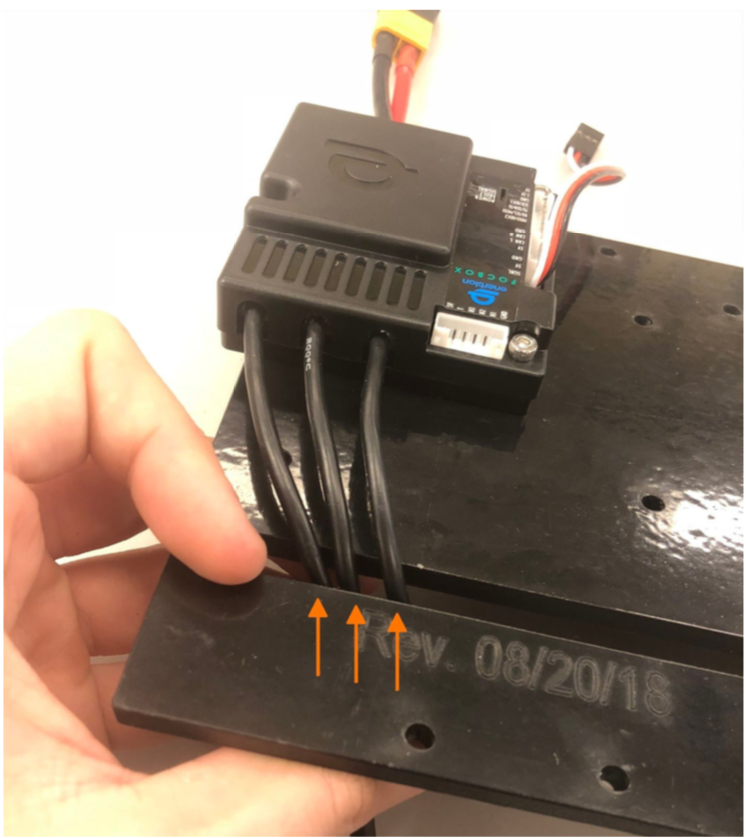

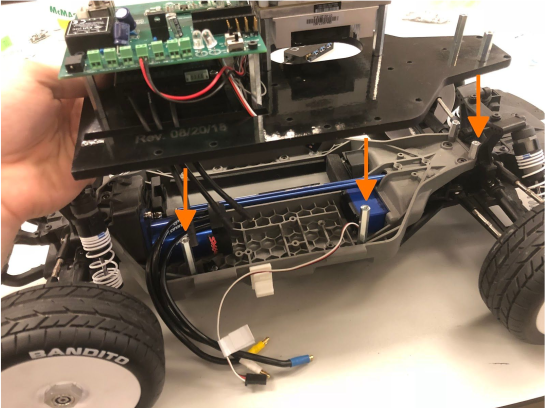

Feed the three motor wires for the FOCbox through the rectangular slot in the chassis as shown below.

Alternate method of securing the FOCbox if screws don’t fit : Some FOCboxes (the more recently-made ones) have smaller screw holes that won’t fit M3-size screws. If this is the case for your FOCbox, you can use a few pieces of double-sided tape to secure the FOCbox instead.

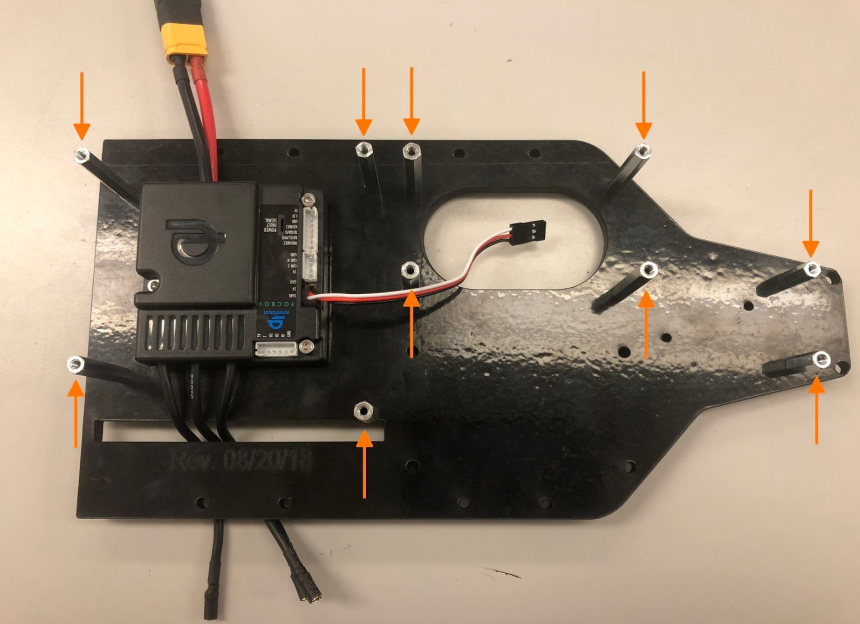

Installing the Chassis Standoffs

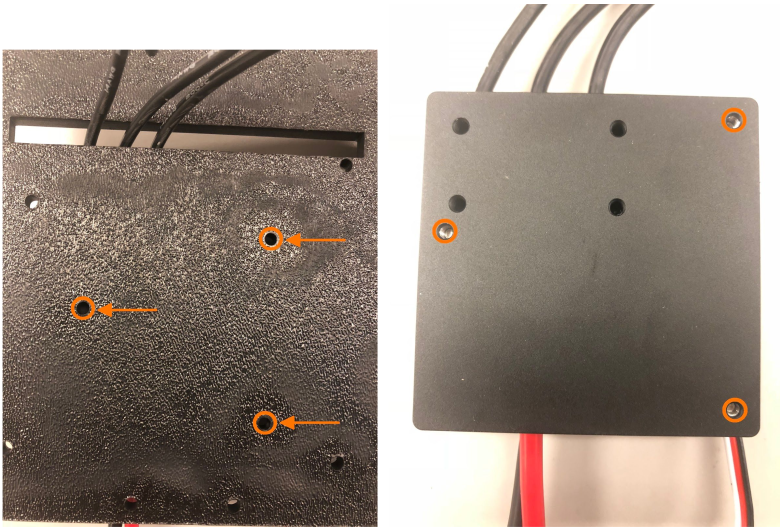

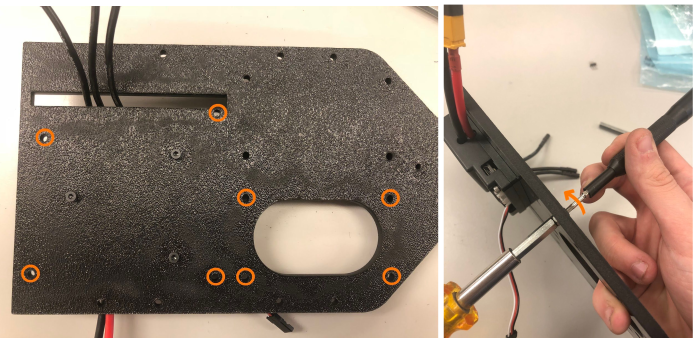

Mount eight 35mm M3 standoffs to the glossy side of the black laser-cut chassis in the positions shown below. Thread 10mm M3 screws through the drill holes and screw them into the standoffs to secure them. ( Important : If you do not mount the standoffs to the glossy side, the power board won't fit since the screw holes will be misaligned.)

Note there are several drill holes in the chassis, so make sure you’re using the right ones. In the image below, the 4 screws on the left(which is the back of the car) will eventually hold the power board, so that’s a good way to see if they’re properly placed. The 4 screws on the right (2 on each side of the oval cutout) will eventually hold the Orbitty carrier attached to the Jetson.

Mount two more (19mm M3) standoffs to the front part of the chassis for the LIDAR, and secure with 10mm screws. The top part of the chassis should look like the picture below.

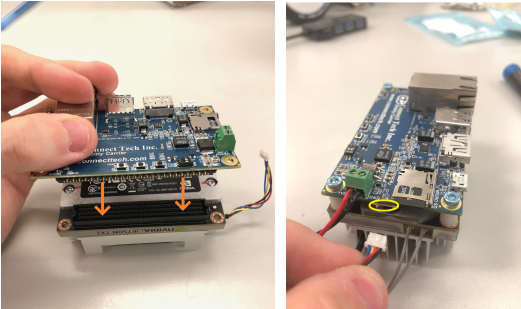

Detaching the Jetson from the Development Board

When you purchase a Jetson, it is attached to a development board. In order to use it on the car, you will need to unscrew the Jetson and its Wi-Fi antenna from the development board.

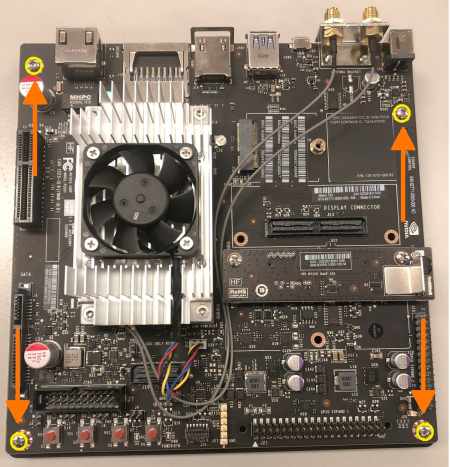

Before you remove the antenna, you will need to remove the bottom plate from the development board. Remove the four screws marked below and lift the development board away from the plate.

Next, remove the Wi-Fi antenna by unscrewing the two screws marked below. Keep the screws in a safe place, as you’ll use them in a bit to attach the antennas to standoffs.

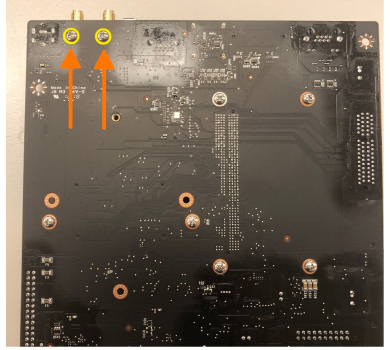

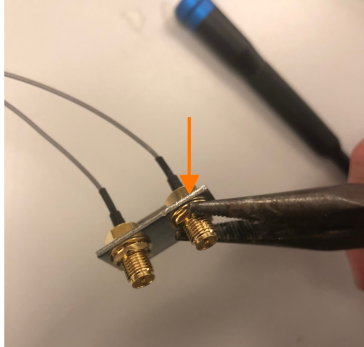

Remove the two brass-colored nuts holding the antennas to the L-shaped bracket, and then remove the two antennas from the bracket. It helps to use two pairs of pliers: one to hold the rear nuts in place and another to unscrew the nuts on the end with the antenna connectors.

Using a Phillips screwdriver, thread the two screws you saved earlier completely into the bracket as pictured below. Attach two standoffs to the opposite ends of the screws and hand-tighten them until they won’t turn anymore. Use the pliers to tighten the standoffs more while you hold the head of the screw in place using the screwdriver. Once you’ve done these steps, place the antennas and washers back into the bracket, and tighten the brass nuts onto the threaded connectors again.

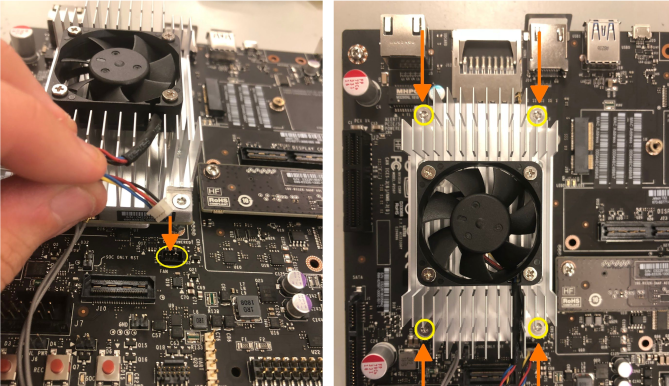

Unplug the Jetson’s fan and remove the Jetson from the development board by using a T3 Torx screwdriver to unscrew the Jetson (the large silver heat sink), and then pull up gently to detach it from the development board. Keep the Jetson in a safe place while you attach the antennas to the power board.

Mounting the Wi-Fi Antennas to the Power Board

Attach the two standoffs for the Wi-Fi antenna bracket to the power board, making sure the antennas, when installed and extended, lie over the board and now away from it. Install the two black antennas onto the threaded connectors if they aren’t already on.

Attach the two wires for the Jetson Wi-Fi antenna to the two gold-colored connectors near the fan connector on the heat sink (the order of the wires doesn’t matter). This can be a little tricky, so you might want to use a flathead screwdriver to ensure the connections are tight. Don’t press too hard , however as you can easily damage the connectors if you use excessive force!

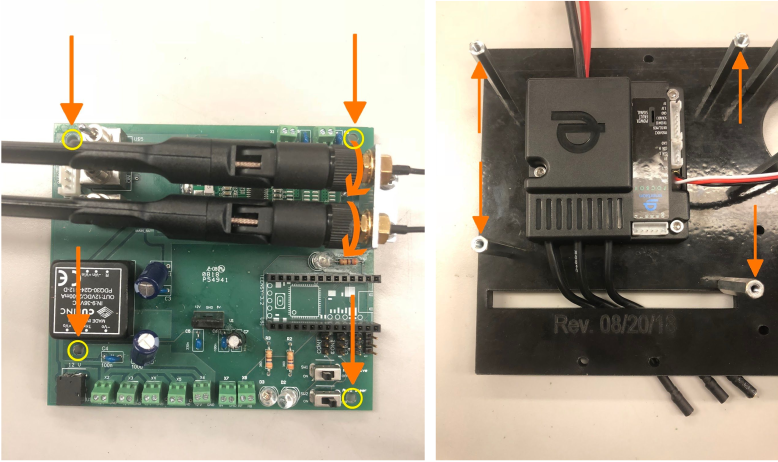

Mounting the Power Board to the Chassis

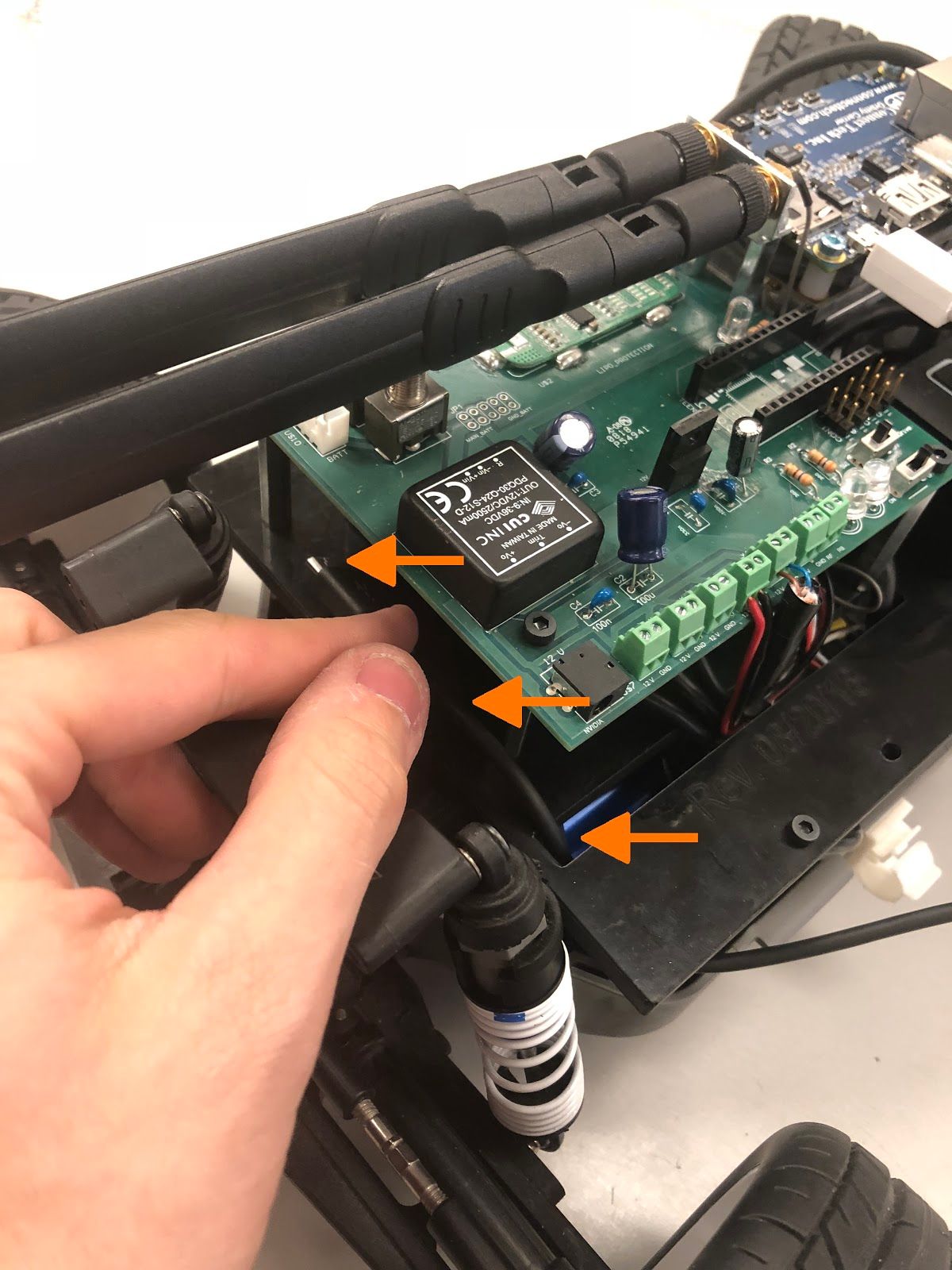

Screw the power board onto its chassis standoffs using 10mm M3 screws. The screw positions are indicated with arrows below.

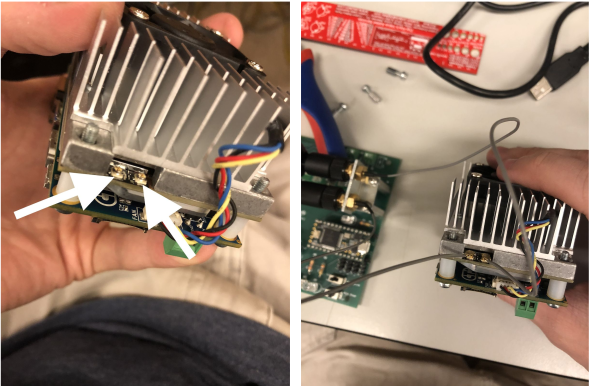

Attaching the Orbitty to the Jetson

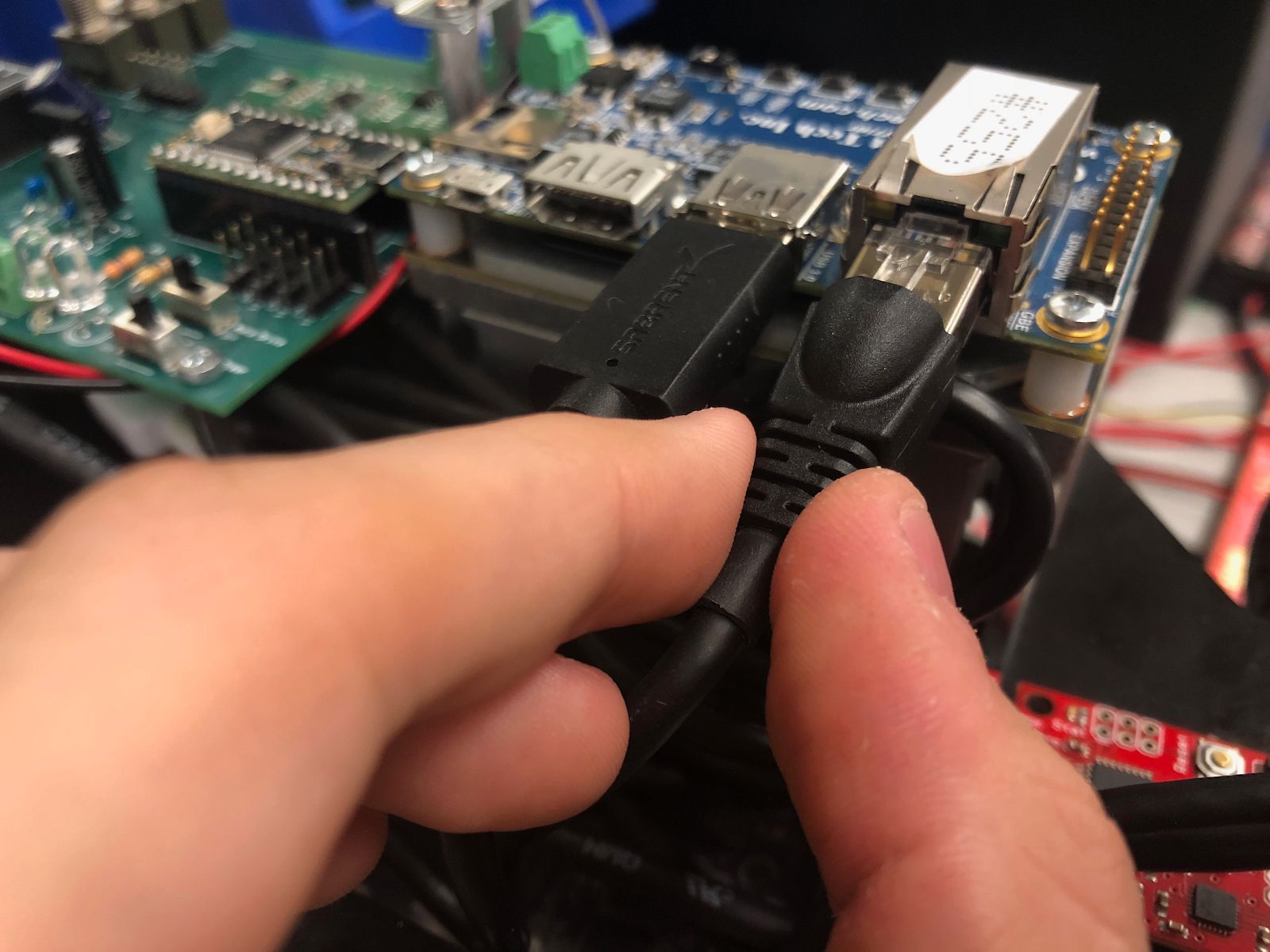

Attach the Orbitty to the Jetson by connecting the two long black ports and connect the Jetson’s fan to the Orbitty’s fan connector as shown in the pictures below.

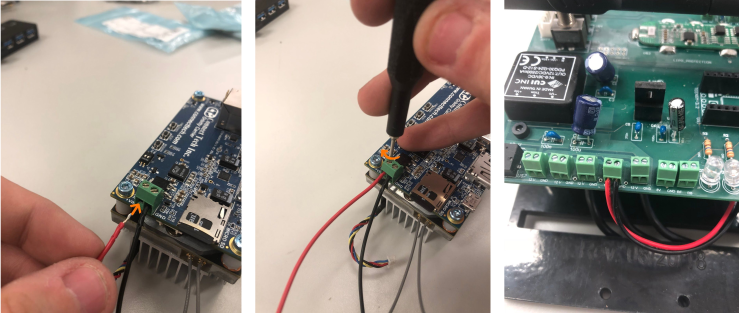

Connecting the Jetson and Power Board

Cut two 8-inch pieces of wire of different colors (preferably red and black), and strip both ends to a short length (1/8 inch). Locate the green terminal block on the Jetson and attach one end of one wire to the + Vin terminal, and the other end to one of the green 1 2V terminals on the power board. (Any of the 12 volt terminals are acceptable. To attach, insert the stripped end into the terminal and screw the little screw tight with a small flathead screwdriver.) Attach the other stripped wire to the G ND terminal on the Jetson and to the G ND terminal on the corresponding terminal block on the power board.

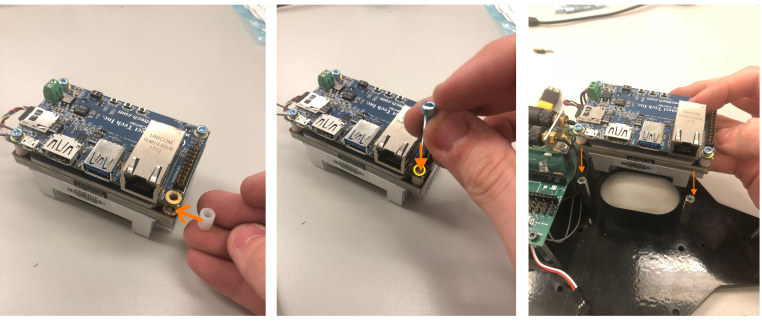

Mounting the Jetson to the Chassis

Your kit comes with four white plastic standoffs; place these between the Jetson PCB and heatsink (see picture) before threading the screws through. Otherwise, you risk bending the Orbitty while screwing it in. Use 20mm screws to secure the Jetson to its chassis standoffs.

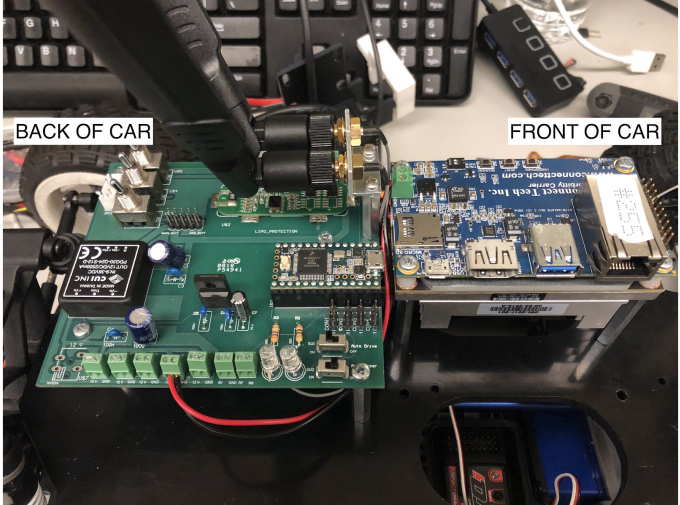

Ensure that when you mount the Jetson that the wires for neither the Wi-Fi antenna nor the Jetson's power connections get pinched. It might help to tuck both sets of wires underneath the power board. (Don't tuck them underneath the Jetson because they might restrict airflow or obstruct the fan's blades.) Your configuration should now look something like this:

Mounting the Chassis to the Car Underbody

Place the chassis onto the five standoffs on the car base and align the chassis’ drill holes with the car’s base standoffs you attached earlier as shown below. Use six 10mm M3 screws to secure the chassis to the standoffs.

Mounting the LIDAR

The LIDAR should have two cords: one for power and another for either Ethernet or USB. Cut the end of the power cord, leaving 1-2 feet of cable. Strip the end, cut away all wires except for the blue and brown ones, and strip those two wires to 1/8 inch as shown below.

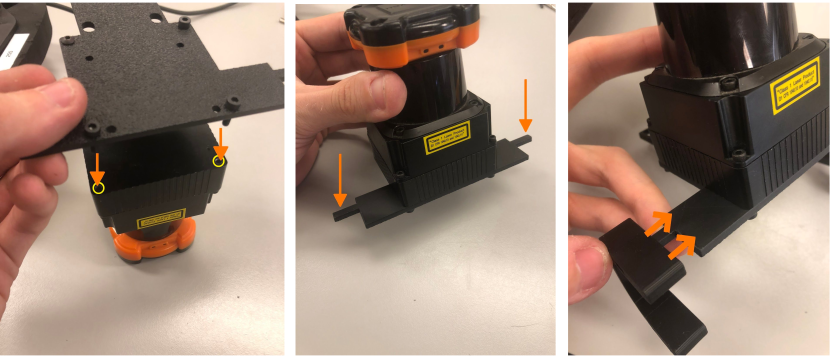

Attach the LIDAR to the tree-shaped base using two (10LX) or four (30LX) screws, such that the wires protruding from the LIDAR go towards the back of the car. (For the 30LX, the two LEDs at the top of the LIDAR should face the front of the car.) Then mount the C-shaped brackets to the black tree-shaped base as shown in the pictures below. Note: if the black mount does not fit in the holes of the C brackets, sand the inserts until they do.

Mount the LIDAR to the car by fitting the two thick protruding parts of the mounting brackets into the holes. The open part of the "C" in the brackets should face forward as shown below.

If you completed the previous steps correctly, two of the holes on the narrow end of the LIDAR base should match up with the two 19mm standoffs you mounted earlier. Wind the power and USB cords of the LIDAR around its base so that there is just enough available to plug into the power board and Jetson, with a little bit of slack so that it is not too tight. Tuck both cords under the LIDAR mounting plate between the two silverstandoffs, and secure the LIDAR base to the standoffs on the chassis using two 10mm M3 screws.

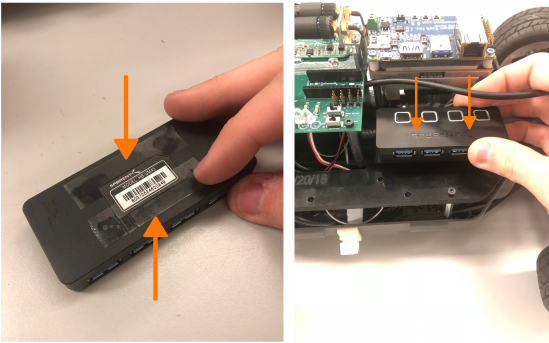

Mounting the USB Hubs

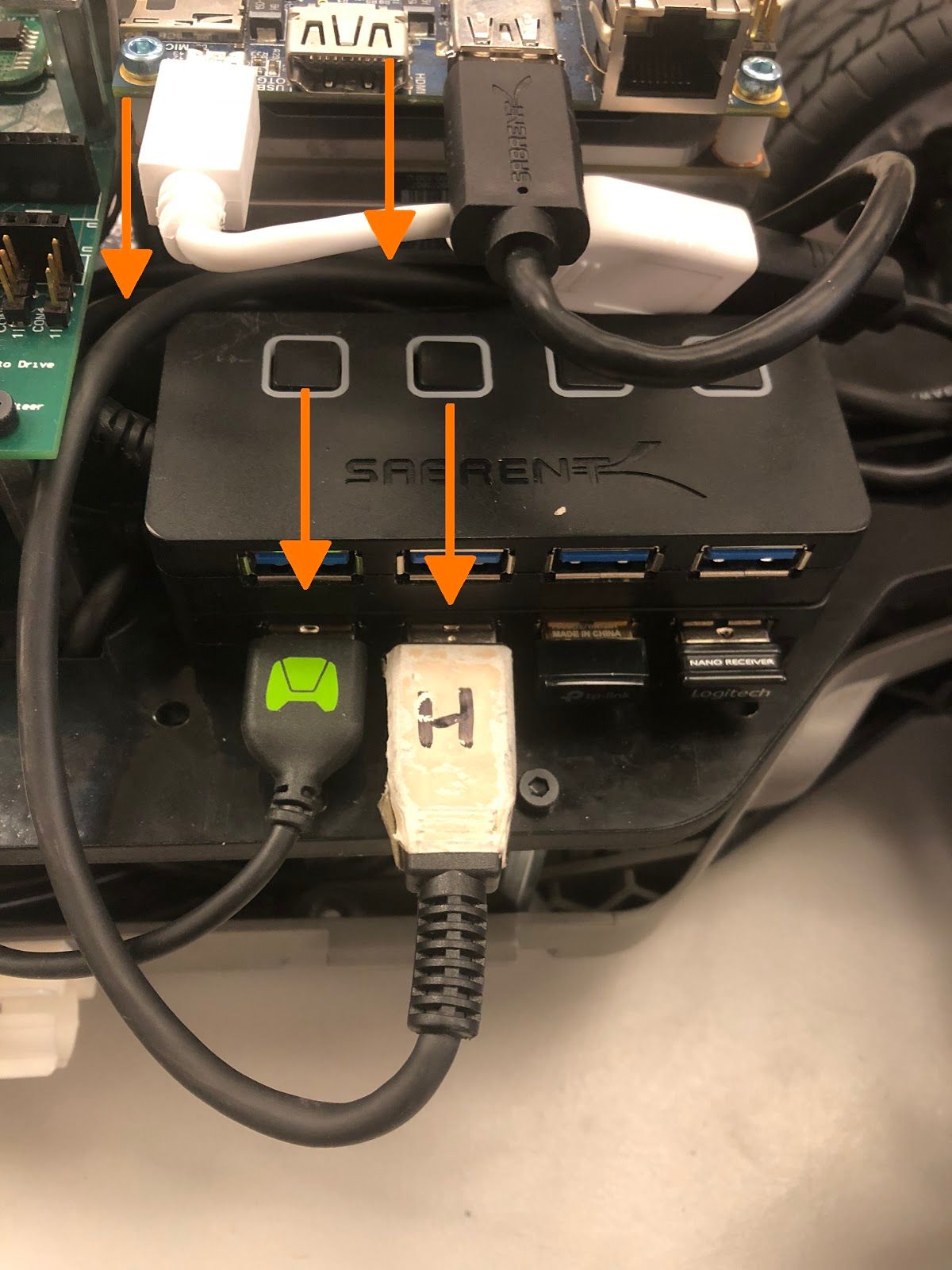

Attack two pieces of double-sided tape to a USB hub. Place the hub onto the empty space of the chassis directly below the Jetson and to the right of the power board as shown. If your hub has power buttons, make sure all of them are turned on.

If you need more USB ports (required if your LiDAR uses USB), you can stack a second hub onto the top of the first. Again, use double-sided tape to secure the second hub and make sure all power buttons are on.

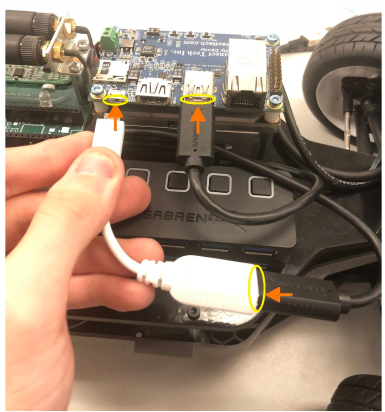

Plug the first USB hub into the Orbitty board. If you’re using a second hub, use the white micro USB adapter that comes with the Jetson to plug in the second hub.

Connecting the LIDAR

Attach the LIDAR's power cable to a free 12V terminal block on the power board. The brown wire should go to the 12V terminal, and the blue wire should go to the corresponding GND terminal. The side of the LIDAR has a pinout as well if you forget.

If the LIDAR has an Ethernet cable, attach it to the Ethernet port on the Jetson. If it has a USB cable, plug it into the USB hub. Route any excess cables behind the USB hubs as shown.

Connecting the FOCbox

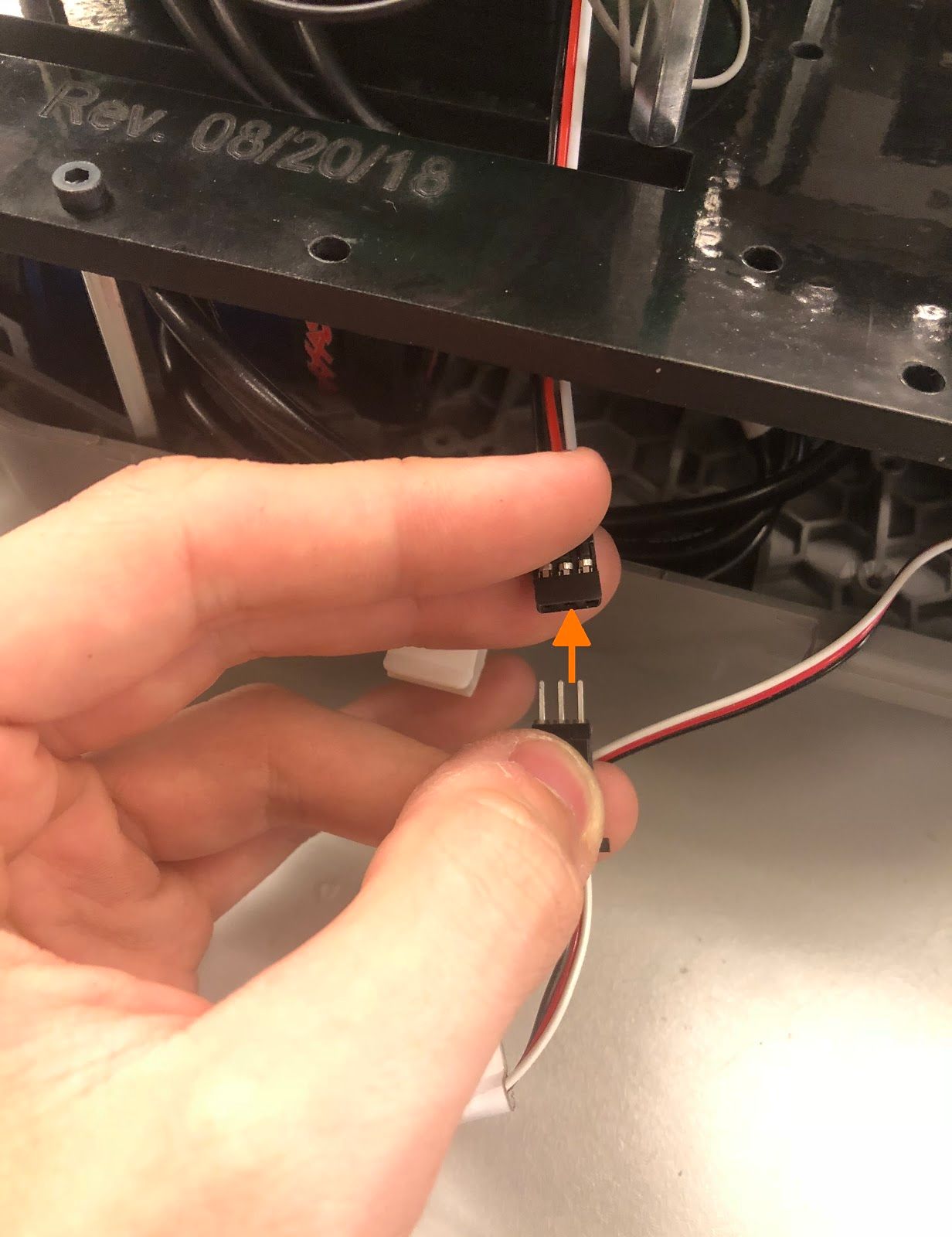

Pass the 3 round FOCbox wires through the rectangular slot in the plastic chassis, then connect the 3 circular bullet connectors to the three motor wires. (The order in which you connect the wires kinda doesn’t matter (electrically speaking). If you run the car and it goes backwards when it should go forwards, you can swap any two of the three wires.) Connect the 3-wire servo ribbon cable as well, making sure the colors match up.

If your micro USB cable is thin enough, thread it through the rectangular wire slot and around the FOCbox to the USB connector as shown below, or route it around the rear end of the chassis if it isn’t. Plug the cable into the FOCbox’s USB connector and into a free port on your USB hub. Tie the USB cable up using a cable tie, and tuck all of the wires underneath the chassis. You can also use this time to plug in the LIDAR (if it is USB), the external Wi-FI adapter, and the receiver for the F710 gamepad.

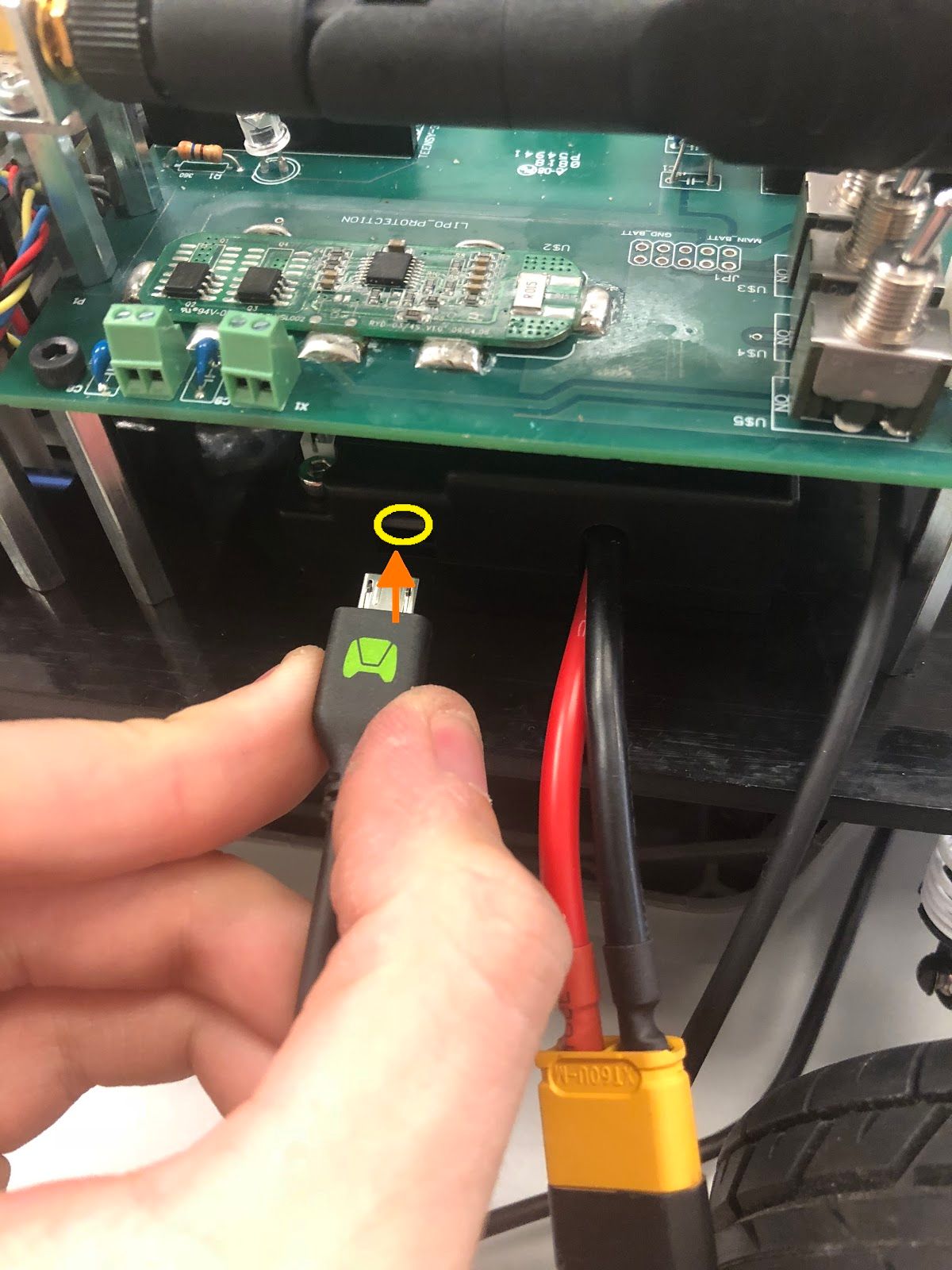

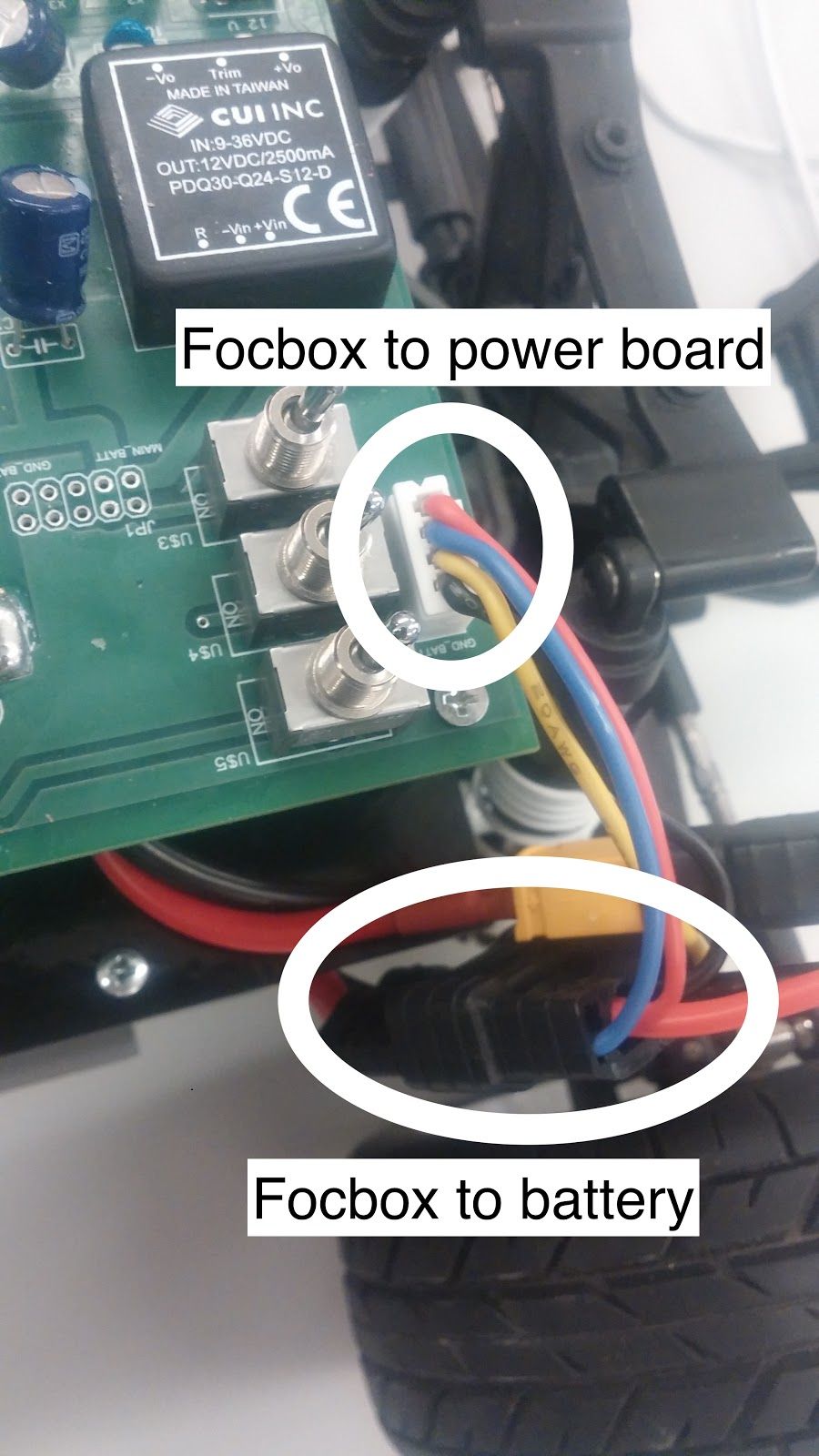

Connecting the Car to the Battery

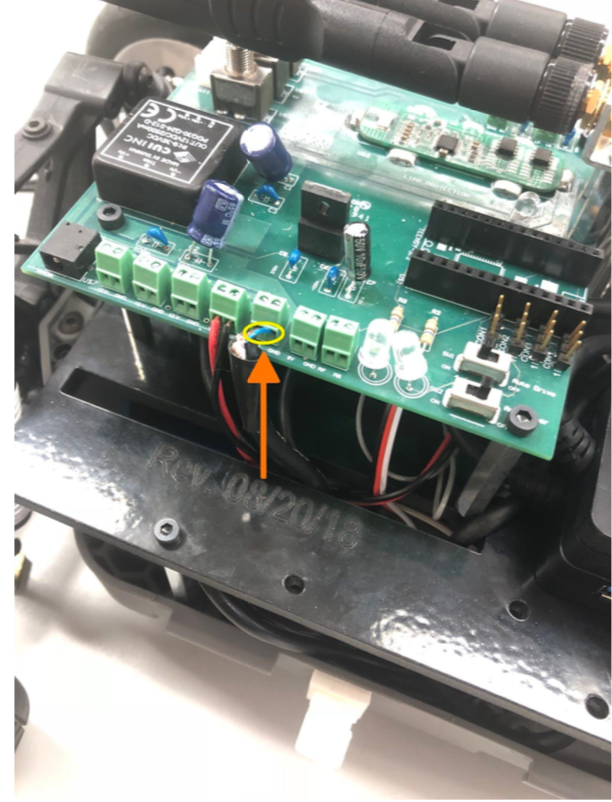

Connect the battery to the FOCbox using the battery connector. Make sure that red is aligned with red and black is aligned with black - otherwise things will get hot and dicey. Then connect the FOCbox to the power board using the white port shown in the picture below.

At this point, your car should be assembled, the Jetson lights should flash when you flip the power switch, and the car is ready to run!

Note: At present, there's no way to know the battery's charge level except by measuring it with a multimeter as it runs. You might consider adding a low voltage LED or seven-segment LCD display (to show the voltage).

Tuning the FOCbox’s PID Gains

In this section we use the words FOCbox and VESC interchangeably.

Important Safety Tips

- Make sure you hold on to the car while testing the motor to prevent it from flying off the stand.

- Make sure there are no objects (or people) in the vicinity of the wheels while testing.

- It’s a good idea to use a fully-charged LiPO battery instead of a power supply to ensure the motor has enough current to spin up.

-

Put your car on an elevated stand so that its wheels can turn without it going anywhere. If you don’t have an RC car stand, you can use the box that came with your Jetson.

-

Connect the host laptop to the FOCbox using a USB cable.

-

Download bldc tool from JetsonHacks, following his instructions for installation.

-

Open BLDC Tool and click the “Connect” button at the top right of the window to connect to the VESC.

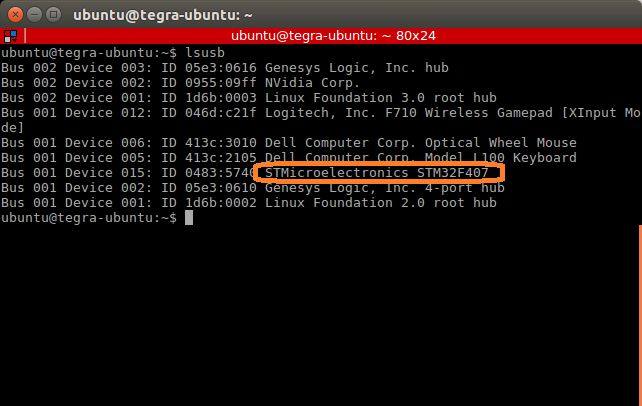

- If you get the error “Device not found”, try running the command lsusb in a terminal. You should see an entry for “STMicroelectronics STMF407” or something similar. If you don’t, try unplugging and plugging in the USB cable on both ends. If the problem doesn’t go away, try rebooting the Jetson.

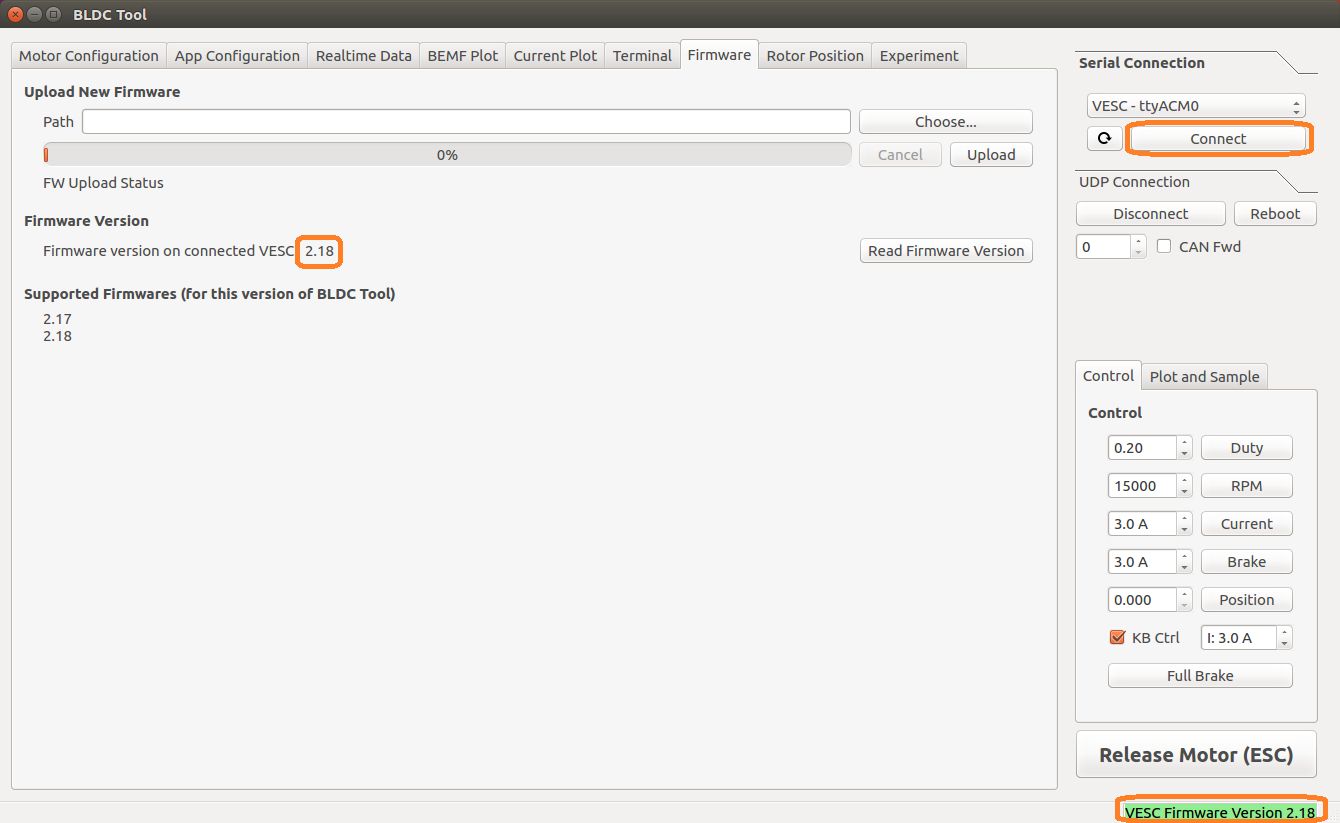

- If you are using a VESC 4.12 (including a FOCbox), ensure the firmware version is 2.18.

-

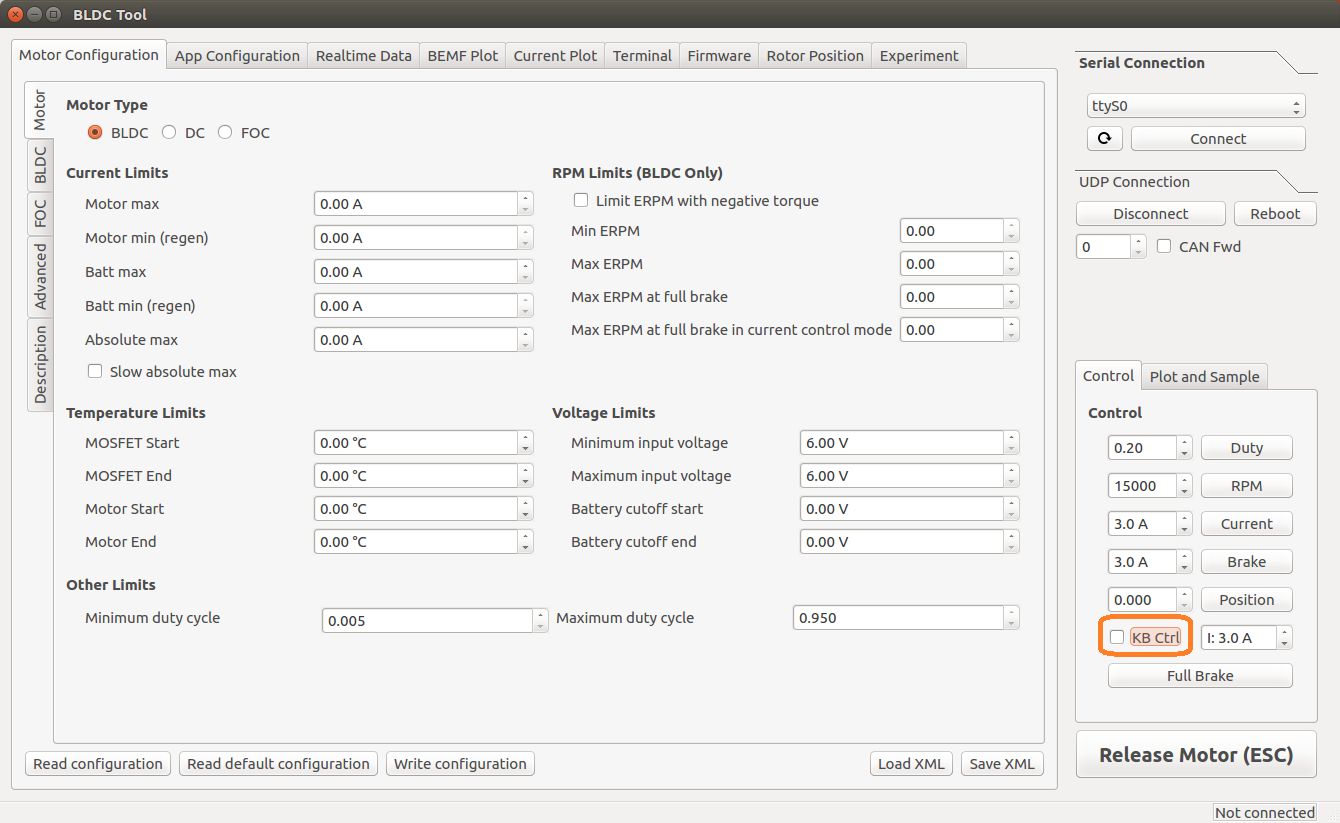

Disable keyboard control by clicking the “KB Ctrl” button at the lower right. This will prevent your keyboard’s arrow keys from controlling the motor and is important to prevent damage to the car from it moving unexpectedly.

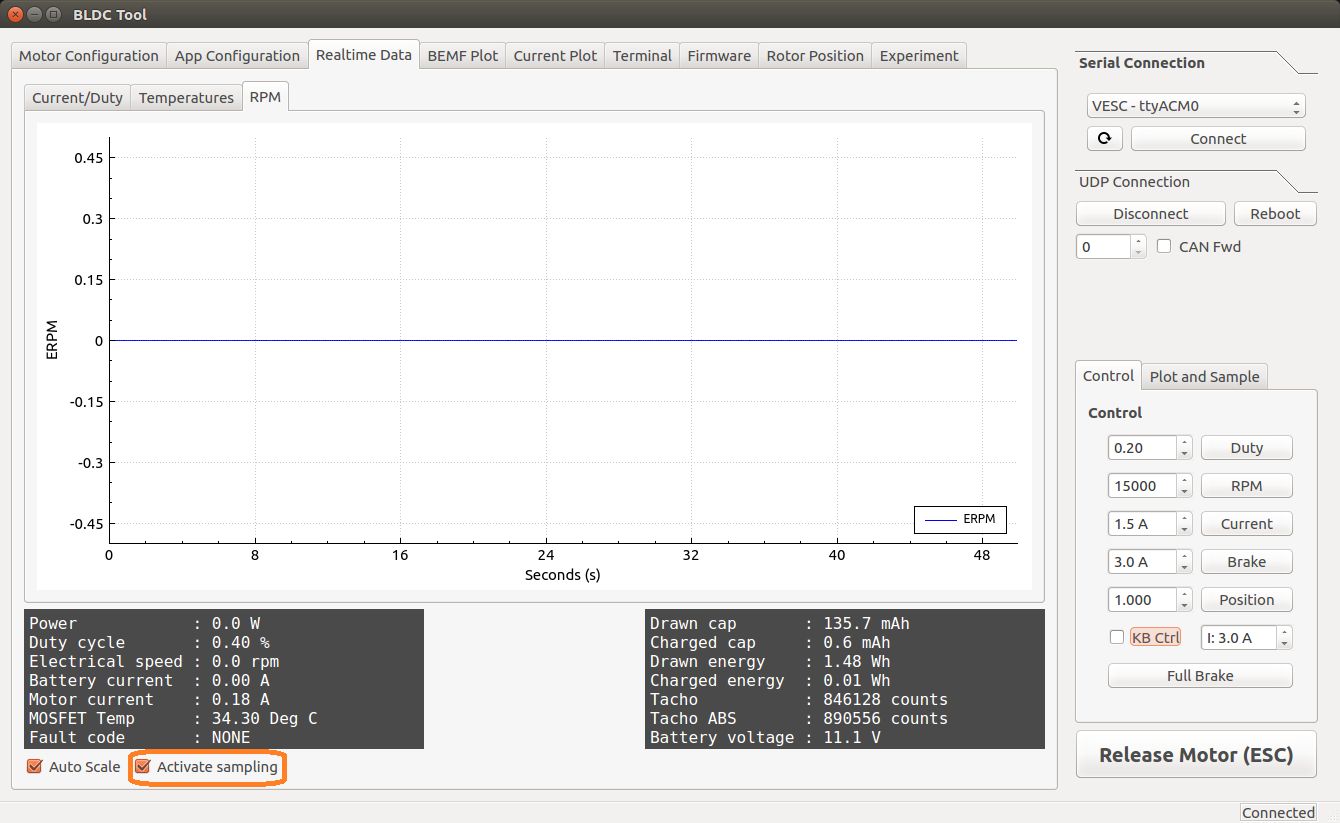

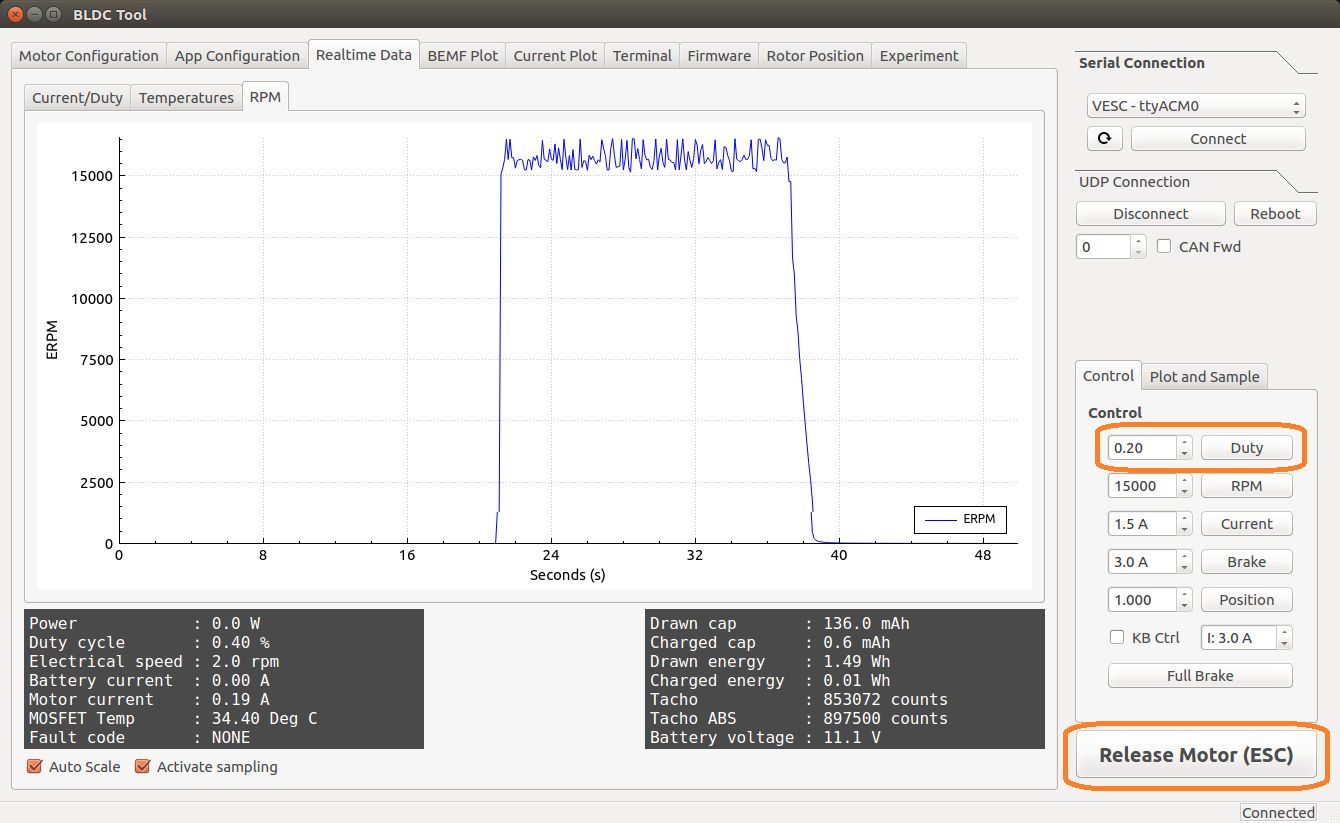

Start plotting the realtime RPM data by clicking the “Realtime Data” tab, and checking the “Activate sampling” checkbox at the bottom left of the window. Click the “RPM” tab above the graph.

- We will keep referring to this plot of the motor’s RPM as we tune the PID gains. Out goal is to get the motor to spin up as quickly as possible when we set it to a certain RPM. We also don’t want the motor to cog (not spin) or overshoot the target speed if possible.

- Test the motor first (without PID speed control) by setting the “Duty Cycle” to 0.20. This will spin the motor up to approximately 16,000 - 17,000 RPM. Let this run for a few seconds, and then press the “Release Motor” button at the bottom right to stop it.

- Observe the RPM graph. If the motor is spinning backwards (the RPM is negative), try reversing two of the connections from the VESC to the motor. (It doesn’t matter which wires you reverse.)

- If the wheels don’t spin and the motor makes no noise, check to make sure all connections to the motor are tight.

- If the wheels don’t spin and the motor does, ensure the motor’s gear is attached correctly to the gearbox at the back of the car. Spin both front wheels with your hand to verify that the gear is making good contact. You should feel some resistance when turning the wheels.

- If the motor doesn’t spin and makes a humming or hissing sound, you might need to replace the motor. If this doesn’t work, try replacing the VESC.

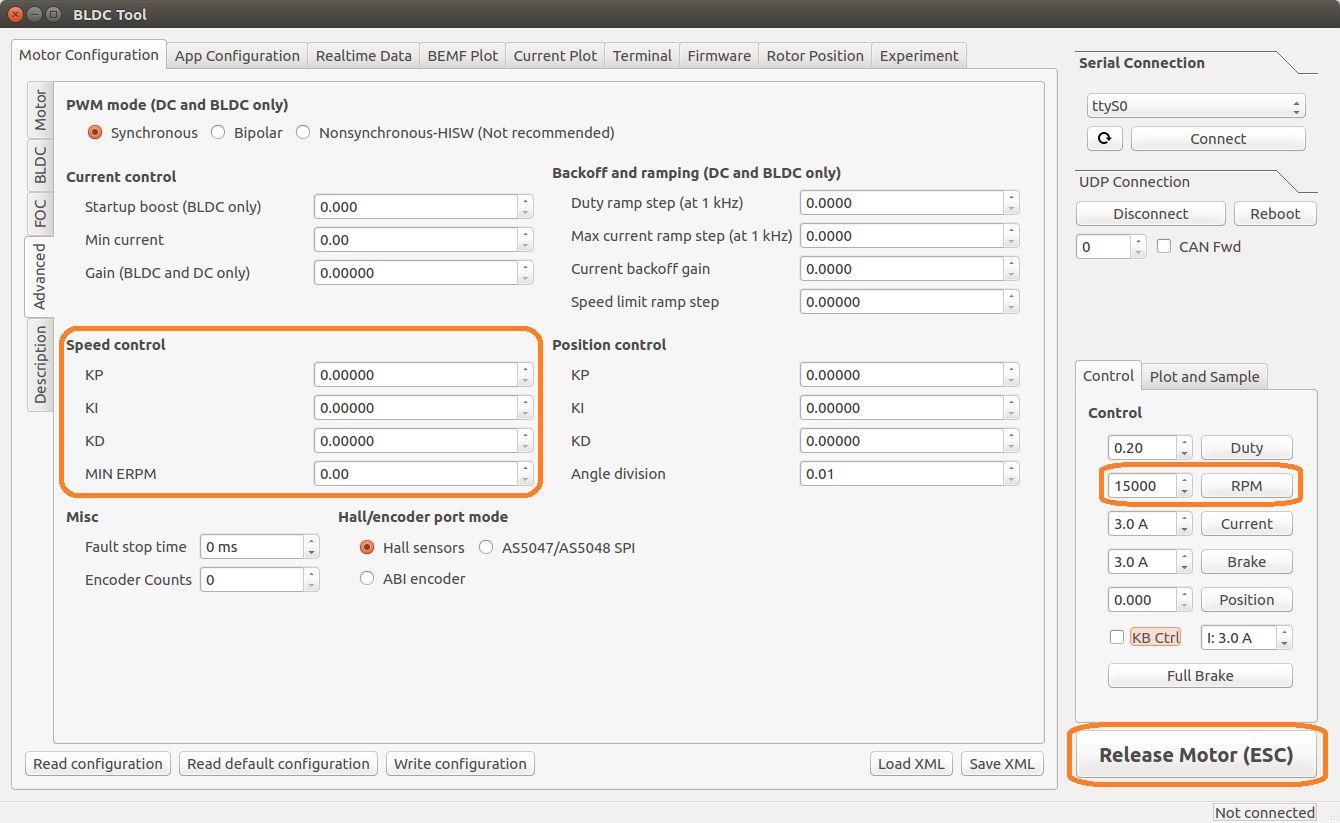

- Click the “Motor Configuration” tab at the top and the “Advanced” tab on the left. Set Ki and Kd to 0.00000, and set Kp to 0.00001. Click the “Write Configuration” button at the bottom, go back to the data plotting tab and run the car at 3000 RPM.

- You will notice that the car won’t even make it close, as it only goes up to around 1200 RPM. (High steady-state error.)

- Try turning Kp up to 0.00002, 0.00004, and 0.00008. (Don’t forget to write the configuration each time.) The motor will start to cog out at higher Kp values.

- Set Kp back to 0.00002, and set Ki to 0.00002, and run the car at 3000 RPM again. Notice how the car slowly reaches the 3000 RPM target. (This is because adding Ki helps to eliminate steady-state error.)

- Keep increasing Ki; set it to 0.00005 and then double that value a few times until the car is able to reach 3000 RPM without overshooting or cogging out.

- Now, try increasing the speed to 6000 RPM.

- The motor might cog out and overshoot. If it does, try halving Kp.

- Increase the speed to 10,000 RPM and then 20,000 RPM. Make sure you hold the car!

- If the motor cogs out and overshoots, halve Kp until it doesn’t.

- It may also help to halve Ki if halving Kp doesn’t work.

- If done correctly, the motor should not overshoot to more than 2 times the set RPM. (That is, if the RPM is set to 15,000, its peak value should not exceed 30,000.)

LiPo (Lithium Polymer) Battery Safety

LiPO batteries allow your car to run for a long time, but they are not something to play with or joke about. They store a large amount of energy in a small space and can damage your car and cause a fire if used improperly. With this in mind, here are some safety tips for using them with the car.

- When charging batteries, always monitor them and place them in a fireproof bag on a non-flammable surface clear of any other objects.

- Do not leave a LIPO battery connected to the car when you’re not using it. The battery will discharge and its voltage will drop to a level too low to charge it safely again.

- Unplug the battery from the car immediately if you notice any popping sounds, bloating of the battery, burning smell, or smoke.

- Never short the battery leads.

- Do not plug the battery in backwards. This will damage the VESC and power board (and likely the Jetson as well) and could cause a short circuit.

See this video and this video for examples of what might happen if you don’t take care of your batteries. Be safe and don’t let these happen to you!

Basic software install

On Your Laptop

Supported Versions

You will need to install the OS Ubuntu Xenial 16.04.01 and ROS Kinetic. Could other combinations work? Sure. Will we support them? Nope.

Install ROS

Go to ROS.org and follow the instructions there to install the version of ROS referenced above.

Note: you might get the following error message when you execute

Building dependency tree

Reading state information... Done

Some packages could not be installed. This may mean that you have requested an impossible situation or if you are using the unstable distribution that some required packages have not yet been created or been moved out of Incoming.

The following information may help to resolve the situation:

The following packages have unmet dependencies:

ros-kinetic-desktop-full : Depends: ros-kinetic-desktop but it is not going to be installed

E: Unable to correct problems, you have held broken packages.

You will find many suggestions online. This one worked for us (I'm installing on a Virtual Machine hosted by a MAC OS).

Specifically, these steps (but it's goot to try the steps in the suggested order):

sudo apt-get -o Debug::pkgProblemResolver=yes dist-upgrade

Then re-run

and re-try installing ros-kinetic-desktop-full

On Jetson

On a high level, these are the things that need to be installed on the Jetson.

- Linux GUI

- Jetpack 3.2 flash

- A re-flash of the Connect Tech Orbitty

- ROS Kinetic

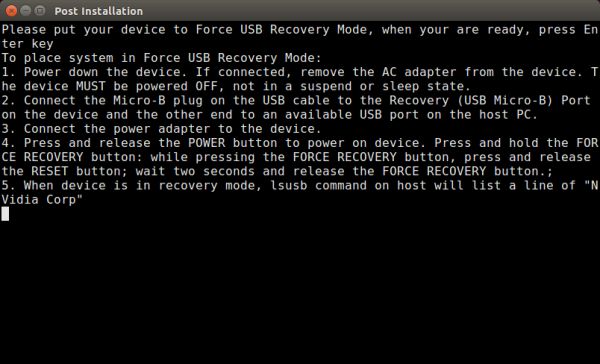

Connect terminals to the Jetson (aka “the device”)

(These instructions are also in the Jeston’s Quick Start Guide under “Force USB Recovery Mode”. Refer to it to see all the buttons, ports and whatnot.)

- Connect a display to the jetson via HDMI port

- Connect a USB keyboard

- Connect the jetson to your host PC via the USB micro-B plug

- Plug to power

The Jetson should power on. If it doesn’t, push the ON button.

Password: nvidia

Install Linux

Run

And run the instructions that are in that file to install Ubuntu Linux. Note that TX1 comes with 14.04 LTS and TX2 comes with 16.04 LTS. There may be an additional step for TX1 if the course is using 16.04 LTS.

Flash the Jetpack

NOTE: you will need some 14GB of free space on the host computer for this step.

Now that we have the GUI, we want to flash the Jetson with Nvidia’s Jetpack 3.2.

To do this, we need a host computer that is running Linux 14.04 (it seems 16.04 also works - try it if that’s what you have). The Jetpack is first downloaded onto the host computer and then transferred by micro USB cable over to the Jetson. Follow the instructions here.

What if you don’t have a Linux 14.04 computer laying around? (most of us don’t). See Appendix A of this doc for an amazing set of instructions by Klein Yuan which details how to use a virtual machine with a Mac to do the flash. Steps would probably work similarly for a PC that is running Virtual Box.

Re-flash the Orbitty

After the Jetson has been flashed with Jetpack, we will actually need to re-flash it with the Connect Tech Orbitty firmware. Otherwise on the TX2 there can be issues with the USB 3.0 not working on the Orbitty carrier board. A great link to instructions is from NVIDIA-Jetson. Note that each time you flash all of the files will essentially be deleted from your Jetson. So make sure to save any work you may have already done and upload it.

Install ROS

Lastly, we will want to install ROS Kinetic. Jetson Hacks on Github has scripts to install ROS Kinetic.

- Here for TX2: https://github.com/jetsonhacks/installROSTX2.

- And here for TX1: https://github.com/jetsonhacks/installROSTX1.

Wireless network setup

We could log into the Jetson using a monitor, keyboard, and mouse, but what about when we’re driving the car? Fortunately, the Jetson has Wi-Fi capability and can be accessed remotely via an SSH session. Throughout this tutorial, you will be asked to configure the Jetson’s and your laptop’s network settings. Make sure to get these right! Using the wrong IP address may lead to conflicts with another classmate, meaning neither of you will be able to connect.

Connecting the Car to the Access Point

- Click the wireless icon at the top right of the screen and click the RoboRacer network to start connecting to it. You will be prompted for a Wi-Fi password for the network: enter the password the TAs give you.

- It’s normal for the wireless icon to appear as if the Jetson is not connected immediately to the network since we still need to assign it an IP address.

- In the same menu, click “Edit Connections.” In the pop-up value that appears, highlight the RoboRacer network and click the Edit button.

- Navigate to the IPv4 Settings tab and, under “Addresses,”, click the Add button.

- In the “Address” field, type 192.168.2.xxx, where xxx is your team’s number plus 200. (For example, if I was on team 2, I would type 192.168.2.202.)

- In the “Netmask” field, type 255.255.255.0.

- In the “Gateway” field, type 192.168.2.1.

- In the “DNS servers” field, type the same entry you used for the default gateway: 192.168.2.1. (The router already has DNS servers configured in its internal settings.)

- You should now be connected. Try opening Chromium and connecting to a site like Google, or using the ping utility from a terminal to test internet connectivity.

- If you experience signal strength issues, try moving closer to the router.

- If you can’t see the router at all, ensure that your Wi-Fi antennas are securely connected to the Jetson. You can also try toggling the adapter on and off via the “Enable Wi-Fi” option in the wireless settings menu.

- If you are connected to the router but can’t reach the internet, you may need to set up the Hokuyo to not allow routing through it.

Connecting Your Computer to the Access Point

Important Note: when connecting your laptop to the router, use an IP address of the form 192.168.2.xxx, where xxx is your team’s number multiplied by 4, added to 100, and then added to a number between 0 and 3 according to the alphabetical order of your last name in your team. For example, if I am on team 2, my name is Jack Harkins, and my teammates are Chris Kao, Sheil Sarda, and Houssam Abbas, I would add 1 since my last name (Harkins) comes second, making my final IP address 192.168.2.209.

Linux

If you’re running Linux in a dual-boot configuration or as a standalone OS, the steps to connect are the same as those for the Jetson above; just make sure you use the correct IP address for your laptop instead of the one for the Jetson. If you’re running Linux in a VM, connect your host computer to the router using the instructions below. Depending on which VM software you have and the default VM configuration, you may also need to set its network adapter configuration to NAT mode. This ensures your VM will share the wireless connection with your host OS instead of controlling the adapter itself.

Windows

These instructions are for Windows 10, but they should be easily replicable on older Windows versions as well.

- Click the wireless icon at the bottom right of the taskbar, select the RoboRacer network, and click the Connect button. Enter the network password when prompted.

- Right-click the same wireless icon and click “Open Network & Internet settings.” Click “Change connection properties” in the window that pops up.

- Scroll down, and under “IP settings,” hit the Edit button. Change “Automatic (DHCP)” to manual, click the IPv4 slider, and enter the IP address, gateway, and DNS server as described previously.

- “Subnet prefix” should be set to 24, not 255.255.255.0 as you did with the Jetson.

- You can leave “Alternate DNS” blank.

- Remember to use the correct IP address for your computer; it should be different from the one you used on the car.)

- If successful, the yellow exclamation mark on the wireless icon should go away. You can test connectivity using the ping utility included with the Windows command prompt.

Mac OS

Coming Soon

SSHing into the Car

The ssh utility is useful for gaining terminal access to your car when you don’t have a monitor around and when you don’t need to do visualization (e.g. via rviz). Using this utility will give you the ability to edit and run your ROS code remotely and is especially useful when you want to rapidly develop and test new algorithms without the hassle a monitor can bring.

Before doing this, make sure both your laptop and car are connected to the RoboRacer network as described here.

- Open a terminal on your laptop and type $ ssh

your car’s IP address to connect to the car. You will be prompted for your Jetson login password; type this in as well. - The first time you SSH into the car, you will probably be told that the “authenticity of the host can’t be established.” Just type in “yes” and the dialog will not appear again.

- If successful, you should see a prompt similar to ubuntu@tegra-ubuntu:~$, which indicates that you’re now connected to the car’s terminal. Try starting roscore and running some ROS scripts. Don’t forget to source your working directory’s setup file beforehand.

- Don’t forget that while you’re SSH’ed into the car, you’re running over the wireless network. Try not to get too far away from the car so you don’t accidentally get logged out, and make sure you save your work often.

Setting Up Wireless Hot Spot on Jetson

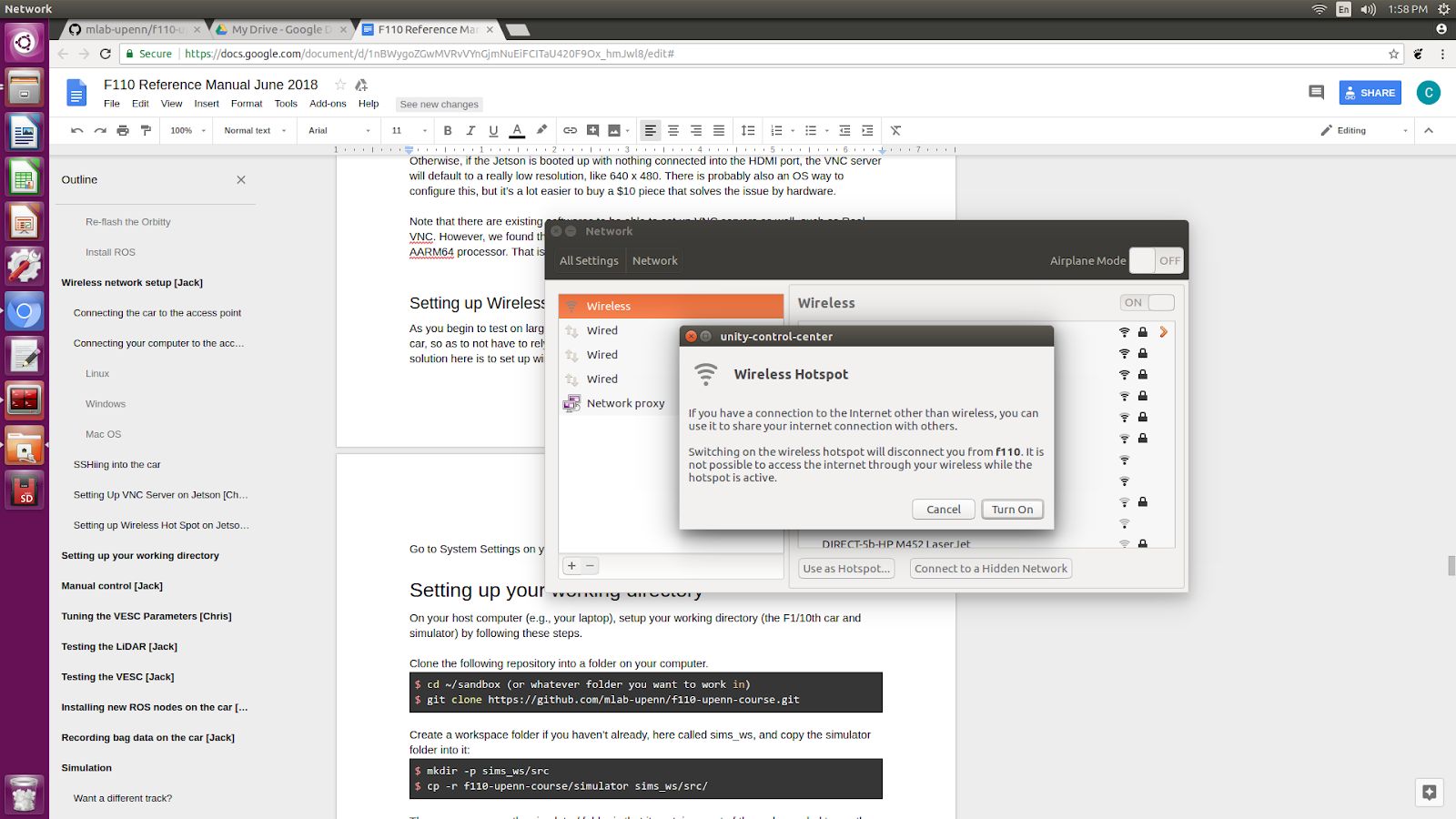

As you begin to test on larger tracks, you may find a need to have a direct connection to your car, so as to not have to rely on the car being within a certain distance of your router. The solution here is to set up wireless hot spot on the Jetson. It is extremely easy.

Go to System Settings on your Jetson. Then Network.

On the bottom center of the pop-up window for the network, click on “Use as Hotspot...” You will no longer have internet connection because your wireless antennas will now be used as a hot spot rather than to connect to the previous Wi-Fi connection that you were on.

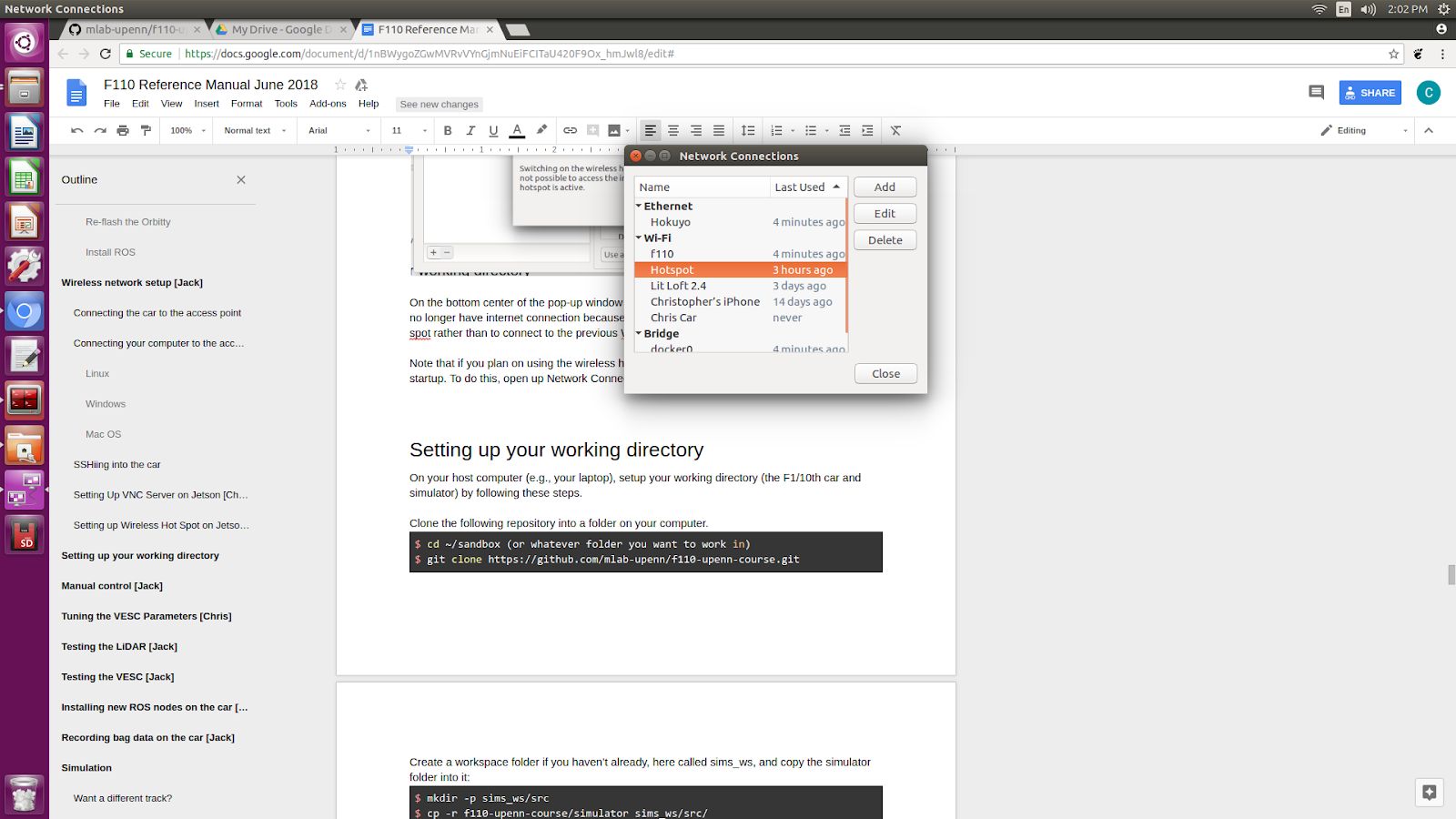

Note that if you plan on using the wireless hotspot feature often, you will want it to boot up on startup. To do this, open up Network Connections, under Wi-Fi select Hotspot and Edit.

Under General click on “Automatically connect to this network when available”.

On your phone, tablet, or laptop you can now connect directly to this Hotspot, and you can use it with VNC viewer as well if you have set up a VNC server. The default IP address for Hotspot on the Jetson is 10.42.0.1.

Setting Up VNC Server on Jetson

(This is not essential, just useful if you feel strongly about having a GUI-type of desktop)

Setting up a VNC server on the Jetson allows you to control the Jetson remotely. Why is this beneficial? When the car is running in the real world we won’t be able to connect the Jetson to an HDMI display. The traditional solution has been to ssh into the Jetson to see the directories, but what if we want to see graphical programs such as Rviz? (in order to see laser scans in live time and camera feeds). Or what if we want to be able to see multiple terminal windows open on the Jetson? A VNC server does this trick.

Here are sequential instructions to install x11vnc and set it up so it loads every time at boot up, taken from http://c-nergy.be/blog/?p=10426 . The article linked contains a link to a shell file to launch all these instructions. We have just pasted it here in case the original article or its link become inaccessible.

# ##################################################################

# Script Name : vnc-startup.sh

# Description : Perform an automated install of X11Vnc

# Configure it to run at startup of the machine

# Date : Feb 2016

# Written by : Griffon

# Web Site :http://www.c-nergy.be - http://www.c-nergy.be/blog

# Version : 1.0

#

# Disclaimer : Script provided AS IS. Use it at your own risk....

#

# #################################################################

# Step 1 - Install X11VNC

# #################################################################

sudo apt-get install x11vnc -y

# Step 2 - Specify Password to be used for VNC Connection

# #################################################################

sudo x11vnc -storepasswd /etc/x11vnc.pass

# Step 3 - Create the Service Unit File

# #################################################################

cat > /lib/systemd/system/x11vnc.service << EOF

[Unit]

Description=Start x11vnc at startup.

After=multi-user.target

[Service]

Type=simple

ExecStart=/usr/bin/x11vnc -auth guess -forever -loop -noxdamage -repeat

-rfbauth /etc/x11vnc.pass -rfbport 5900 -shared

[Install]

WantedBy=multi-user.target

EOF

# Step 4 -Configure the Service

# ################################################################

echo "Configure Services"

sudo systemctl enable x11vnc.service

sudo systemctl daemon-reload

sleep 5s

sudo shutdown -r now

Note that if you want to change the port that the VNC server lives on, then simply change 5900 to some other number. The article states that if 5900 is used on the Jetson, then the VNC server will automatically forward through 5901. And if that is taken, then 5902, and so on and so forth.

To connect to your VNC server, use a VNC viewer. A free one that works pretty well is Real VNC’s VNC Viewer. If you are on a mac, you can also use the included Screen Sharing app. Connect by typing into the url [jetson’s ip address]:[port number]. So for instance, if the jetson is connected on ip address 192.168.2.9 with port number 5900, then type in 192.168.2.9:5900.

Lastly, you will want to use an HDMI emulator, like this one, in order to trick the Jetson to thinking that a display is connected so that it will display at higher resolutions by running the GPU. Otherwise, if the Jetson is booted up with nothing connected into the HDMI port, the VNC server will default to a really low resolution, like 640 x 480. There is probably also an OS way to configure this, but it’s a lot easier to buy a $10 piece that solves the issue by hardware.

Note that there are existing softwares to be able to set up VNC servers as well, such as Real VNC. However, we found that these could not install on the Jetson TX2 because it uses an AARM64 processor. That is why we had to use x11vnc.

Hokuyo 10LX ethernet connection setup

Coming Soon: Add pictures and snippets.

In order to utilize the 10LX you must first configure the eth0 network. From the factory the 10LX is assigned the following ip: 192.168.0.10. Note that the lidar is on subnet 0.

First create a new wired connection.

In the ipv4 tab add a route such that the eth0 port on the Jetson is assigned ip address 192.168.0.15, the subnet mask is 255.255.255.0, and the gateway is 192.168.0.1. Call the connection Hokuyo. Save the connection and close the network configuration GUI.

When you plug in the 10LX make sure that the Hokuyo connection is selected. If everything is configured properly you should now be able to ping 192.168.0.1.

In the racecar config folder under ‘lidar_node’ set the following parameter: ‘ip_address: 192.168.0.10’. In addition in the sensors.launch.xml change the argument for the lidar launch from ‘hokuyo_node’ to ‘urg_node’ do the same thing for the node_type parameter.

Working directory setup

On your host computer (e.g., your laptop), setup your working directory (the F1/10th car and simulator) by following these steps.

Clone the following repository into a folder on your computer.

$ git clone https://github.com/mlab-upenn/RoboRacer-fall2018-skeletons.git

Create a workspace folder if you haven’t already, here called f110_ws, and copy the simulator folder into it:

$ cp -r f110-fall2018-skeletons f110_ws/src/

You will need to install these with apt-get in order for the car and Gazebo simulator to work.

$ sudo apt-get install ros-kinetic-ros-control ros-kinetic-ros-controllers ros-kinetic-gazebo-ros-control ros-kinetic-ackermann-msgs ros-kinetic-joy ros-kinetic-driver-base

Make all the Python scripts executable (by default they are set to non-executable when cloned from Github).

$ find . -name “*.py” -exec chmod +x {} \;

Move to your workspace folder and compile the code (catkin_make does more than code compilation - see online reference).

Finally, source your working directory into your shell using

Congratulations! Your working directory is all set up. Now if you examine the contents of your workspace, you will see 3 folders (In the ROS world we call them meta-packages since they contain packages): algorithms, simulator, and system. Algorithms contains the brains of the car which run high level algorithms, such as wall following, pure pursuit, localization. Simulator contains racecar-simulator which is based off of MIT Racecar’s repository and includes some new worlds such as Levine 2nd floor loop. Simulator also contains f1_10_sim which contains some message types useful for passing drive parameters data from the algorithm nodes to the VESC nodes that drive the car. Lastly, System contains code from MIT Racecar that the car would not be able to work without. For instance, System contains ackermann_msgs (for Ackermann steering), racecar (which contains parameters for max speed, sensor IP addresses, and teleoperation), serial (for USB serial communication with VESC), and vesc (written by MIT for VESC to work with the racecar).

udev rules setup

When you connect the VESC and LIDAR to the Jetson, the operating system will assign them device names of the form /dev/ttyACMx, where x is a number that depends on the order in which they were plugged in. For example, if you plug in the LIDAR before you plug in the VESC, the LIDAR will be assigned the name /dev/ttyACM0, and the VESC will be assigned /dev/ttyACM1. This is a problem, as the car’s ROS configuration scripts need to know which device names the LIDAR and VESC are assigned, and these can vary every time we reboot the Jetson, depending on the order in which the devices are initialized.

Fortunately, Linux has a utility named udev that allows us to assign each device a “virtual” name based on its vendor and product IDs. For example, if we plug a USB device in and its vendor ID matches the ID for Hokuyo laser scanners (15d1), udev could assign the device the name /dev/sensors/hokuyo instead of the more generic /dev/ttyACMx. This allows our configuration scripts to refer to things like /dev/sensors/hokuyo and /dev/sensors/vesc, which do not depend on the order in which the devices were initialized. We will use udev to assign persistent device names to the LIDAR, VESC, and joypad by creating three configuration files (“rules”) in the directory /etc/udev/rules.d.

First, as root, open /etc/udev/rules.d/99-hokuyo.rules in a text editor to create a new rules file for the Hokuyo. Copy the following rule exactly as it appears below and save it:

Next, open /etc/udev/rules.d/99-vesc.rules and copy in the following rule for the VESC:

Then open /etc/udev/rules.d/99-joypad-f710.rules and add this rule for the joypad:

Finally, trigger (activate) the rules by running

Reboot your system, and you should find three new devices by running

/dev/sensors/vesc

/dev/input/joypad-f710

If you want to add additional devices and don’t know their vendor or product IDs, you can use the command

making sure to replace <your_device_name> with the name of your device (e.g. ttyACM0 if that’s what the OS assigned it. The Unix utility dmesg can help you find that). The topmost entry will be the entry for your device; lower entries are for the device’s parents.

Manual control

Before we can get the car to drive itself, it’s a good idea to test the car to make sure it can successfully drive on the ground under human control. Controlling the car manually is also a good idea if you’ve recently re-tuned the VESC or swapped out a drivetrain component, such as the motor or gears. Doing this step early can spare you a headache debugging your code later since you will be able to rule out lower-level hardware issues if your code doesn’t work.

Before you begin:

- Make sure you have the car running off its LIPO battery and that you have a Logitech F710 joypad handy with its receiver (i.e., USB dongle) plugged into the Jetson’s USB hub.

- Make sure you have the VESC connected!

- Ensure that both your car and laptop are connected to a wireless access point if you need the car connected to the Internet while you drive it. Otherwise, follow this tutorial so your laptop and phone can connect directly to the car.

- Make sure you’ve cloned the course repository and set up your working directory (as explained here)

- This tutorial uses the program tmux (available via apt-get) to let you run multiple terminals over one SSH connection. You can also use VNC if you prefer a GUI.

Now, we’re ready to begin.

- Open a terminal and SSH into the car from your computer. Once you’re in, run tmux so that you can spawn new terminal sessions over the same SSH connection.

- In your tmux session, spawn a new window (using Ctrl-A “) and run roscore to start ROS.

- In the other free terminal, navigate to your working directory, run $ catkin make and source the directory using $ source devel/setup.bash.

- Run roslaunch racecar teleop.launch to launch the car. Place the car on the ground and press the center button on your joystick so you can control the car. If this gives you a segmentation error, and it’s caused by compiling the joy package (which you can check by running the joy_node on its own), this could be because you are using the joy package from the ROS distribution (i.e., installed with apt-get). Remove that (sudo apt-get remove joy) and re-compile. This should compile the joy package that’s in the repo.

- Hold the LB button on the controller to start controlling the car. Use the left joystick to move the car forward and backward and the right joystick for steering.

- If nothing happens, one reason can be that the joy_node is listening for inputs on the js0 port, but the OS has assigned a different port to it, like js1. Edit the yaml file which specifies which port to listen to. You can tell what file that is by reading the launch file (and following the call tree to other launch files).

- Note that the LB button acts as a “dead man’s switch,” as releasing it will stop the car. This is for safety in case your car gets out of control.

- You can see a mapping of all controls used by the car in <your catkin workspace>/src/racecar/racecar/config/racecar-v2/joy_teleo p.yaml. For example, in the default configuration, axis 1 (left joystick’s vertical axis) is used for throttle, and axis 2 (right joystick’s horizontal axis) is used for steering.

Troubleshooting

- If you’re getting “VESC out of sync errors”, check that the VESC is connected

- If you get “SerialException” types of messages, and you’re using the 30LX Hokuyo, the errors might be due to a port conflict: e.g., suppose that the lidar was assigned the (virtual serial bi-directional) port ttyACM0 by the OS. And suppose that the vesc_node is told the VESC is connected to port ttyACM0 (as per vesc.yaml). Then when the vesc_node receives joystick commands from joy_node (via ROS), it pushes them to ACM0 - so these messages actually go to the lidar, and the VESC gets garbage back. So change the vesc.yaml port entry to ttyACM1. (This whole discussion remains valid if you switch 0 and 1, i.e. if the OS assigned ACM1 to the lidar and your vesc.yaml lists ACM1). Note that everytime you power down and up, the OS will assign ports from scratch, which might again break your config files. So a better solution is to use udev rules, as explained in this section. (See joy_node.cpp for the default port for the joystick. You can over-ride that using a parameter in the launch file. See the joy documentation for what parameter that is).

- If you get urg_node related error messages, check the ports (e.g. an ip address in sensors.yaml can only be used by 10LX, not 30LX, and vice-versa for the /dev/ttyACMn).

- If you get razor_imu errors, delete the IMU entry from the launch file - we’re not using an IMU in this build.

Tuning the VESC Parameters

You may want to fine tune your VESC parameters to match them to your car. Why? You might notice that your car with the default parameters drifts slightly to the side, or isn’t going as fast as you want it to. In order to tune your VESC parameters, navigate to racecar/racecar/config/racecar-v2/vesc.yaml. The vesc.yaml file is a configuration file where you can set parameters for erpm gain, steering angle offset, speed_min, speed_max, etc.

If you want to modify the maximum speed, under vesc_driver you can change the speed_min and speed_max. These numbers represent the erpm of the car. By default they are set to +/- 3000 but you can set them higher, up to around 10,000. By default where speed_max is 3000 even though the joystick is telling the car to go 2 m/s (which corresponds to speed_to_erpm_gain * 2 = 9,228) your car will be limited by the 3000 erpm when 2 m/s actually corresponds to 9,228 erpm.

If your car’s motor is using a smaller or larger gear (where larger gear means you need lower erpm in order to achieve a certain speed), you will want to compensate for this by adjusting the speed_to_erpm_gain. For instance, I had to raise my speed_to_erpm_gain from the default setting of 4614 to 7442. The reason is that my motor has a smaller gear attached to it (they are swappable), so it needs more rotations in order to achieve the same speed. If I hadn’t increased the speed_to_erpm_gain, even though I was telling the car to go 2 m/s, in reality it was only going 1.2 m/s. And this was problematic because my /vesc/odom topic was publishing incorrect measurements - it was overestimating how far the car had traveled.

If you notice that your car is not going straight, then you will want to modify your steering_angle_to_servo_offset. By default the value is around 0.53, and you’ll want to increase or decrease this slightly until the car is going straight.

Other than these three parameters above, I didn’t change anything else but you are welcome to play around with these as you see fit. It’s a great learning experience!

Testing the LiDAR (USB only)

Once you’ve set up the LIDAR, you can test it using urg_node, rviz, and rostopic.

- Connect the LiDAR to the power board (see section Connecting the LIDAR), and plug the USB cable into a free port on your hub.

- Start roscore in a terminal window.

- In another (new) terminal window, run rosrun urg_node urg_node. This tells ROS to start reading from the LIDAR and publishing on the /scan topic.

- If you get an error saying that there is an “error connecting to Hokuyo,” double check that the Hokuyo is physically plugged into a USB port. You can use the terminal command lsusb to check whether Linux successfully detected your LiDAR.

- If the node started and is publishing correctly, you should be able to use rostopic echo /scan to see live LIDAR data.

- Open another terminal and run rosrun rviz rviz to visually see the data. When rviz opens, click the “Add” button at the lower left corner. A dialog will pop up; from here, click the “By topic” tab, highlight the “LaserScan” topic, and click OK.

- rviz will now show a collection of points (a point cloud) of the LIDAR data in the gray grid in the center of the screen. The points appear in colors ranging from green to red, with green points being closest to the LIDAR and red points being farthest away.

- Try moving a flat object, such as a book, in front of the LIDAR and to its sides. You should see a corresponding flat line of points on the rviz grid.

- Try picking the car up and moving it around, and note how the LIDAR scan data changes,

- You can also see the LIDAR data in text form by using rostopic echo /scan. The type of message published to it is sensor_msgs/Scan, which you can also see by running rostopic info /scan. There are many fields in this message type, but for our course, the most important one is ranges, which is a list of distances the sensor records in order as it sweeps from its rightmost position to its leftmost position.

Recording bag data on the car

ROSbags are useful for recording data from the car (e.g. LIDAR, wheel rotation) and playing it back later. This feature is useful because it allows you to capture data from when the car is running and later study the data or perform analysis on it to help you develop and implement better racing algorithms.

One great thing about ROSbags compared to just recording the data into something simpler (like a CSV file) is that data is recorded along with the topics it was originally sent on. What this means is that when you later play the bag, the data will be transmitted on the same topics that it was originally sent on, and any code that was listening to these topics can run, as if the data was being generated live.

For example, suppose I record LIDAR data being broadcasted on the /scan topic. When I later play the data back, the rostopic list and rostopic echo commands will show the LIDAR data being transmitted on the /scan topic as if the car was actually running!

Here’s a concrete example of how to use ROSbags to acquire motor telemetry data and play it back.

- Make sure both your computer and car are connected to the f110 access point. Also, make sure your car is connected with a known static IP address.

- Open a terminal and SSH into the car. Once you’re in, run tmux so that you can spawn new terminal sessions over the same SSH connection.

- Follow the directions to clone the racecar repositories (more instructions coming soon). Clone these into your ROS working directory.

- In your tmux session, spawn a new window (using Ctrl-A “) and run roscore to start ROS.

- In the other free terminal, navigate to your working directory, run catkin make, and source the directory using source devel/setup.bash.

- Run roslaunch racecar teleop.launch to launch the car. Place the car on the ground or on a stand and press the center button on your joystick so you can control the car.

- In your tmux session, spawn a new window and examine the list of active ROS topics using rostopic list. Make sure that you can see the /vesc/sensors/core topic, which contains drive motor parameters.

- Here’s where ROSbags come into play. Run rosbag record /vesc/sensors/core to start recording the data. The data will start recording to a file in the current directory with naming format YYYY-MM-DD-HH-MM-SS.bag. Recording will continue until you press Control-C to kill the rosbag process.

- If you get an error about low disk space, you can specify the directory to record to (e.g. on a USB flash drive or hard drive) after the topic name). For example, on my system, I would type rosbag record /vesc/sensors/core -o /media/ubuntu/Seagate\ Backup\ Plus\ Drive/ to record into the root of my external hard drive.

- Note that rosbag also supports recording multiple topics at the same time. For example, I could record both laser scan and motor data using rosbag record /vesc/sensors/core /scan

- Let the recording run for about 30 seconds. Drive the car around during this time using the controller and then hit Control-C to stop recording. (Important: Quit the running teleop.launch as well.)

- Play the rosbag file using rosbag play <your rosbag file>. While the bag is playing, examine the topics list, and you will see a list of all topics that were recorded into the bag. Note that in addition to the topics you specified, ROS will also record the rosout, rosout_agg, and clock topics, which can be useful for debugging.

- View that recorded motor data by echoing the /vesc/sensors/core topic. Pay attention to how the motor RPM changed as you drove the car around. When the bag is out of data, it will stop publishing.

Simulation

Why would we want to use a simulator? We want to test the car’s algorithms in a controlled environment before we bring it into the real world so that we minimize risk of crashing. If you’ve ever had to fix a Traxxas RC car before, you might know that they can be a pain to fix. For instance, if a front steering servo plastic piece were to break, we would have to disassemble about 20 parts in order to replace it. The simulator will be our best friend for quite a while during development.

We will use the ROS Gazebo simulator software. From a high level, Gazebo loads a world as a .DAE file and loads the car. It has a physics engine that can determine when the car crashes into a wall.

First, ensure that you have setup your working directory as shown in the instructions here. Next, in the workspace folder, run:

$ roslaunch wall_following wall_following.launch

(What is this roslaunch command? See here. Syntax highlighting (section 5 of that page) also helps. Note that roslaunch will also start the ROS master node so you don’t need to run roscore separately)

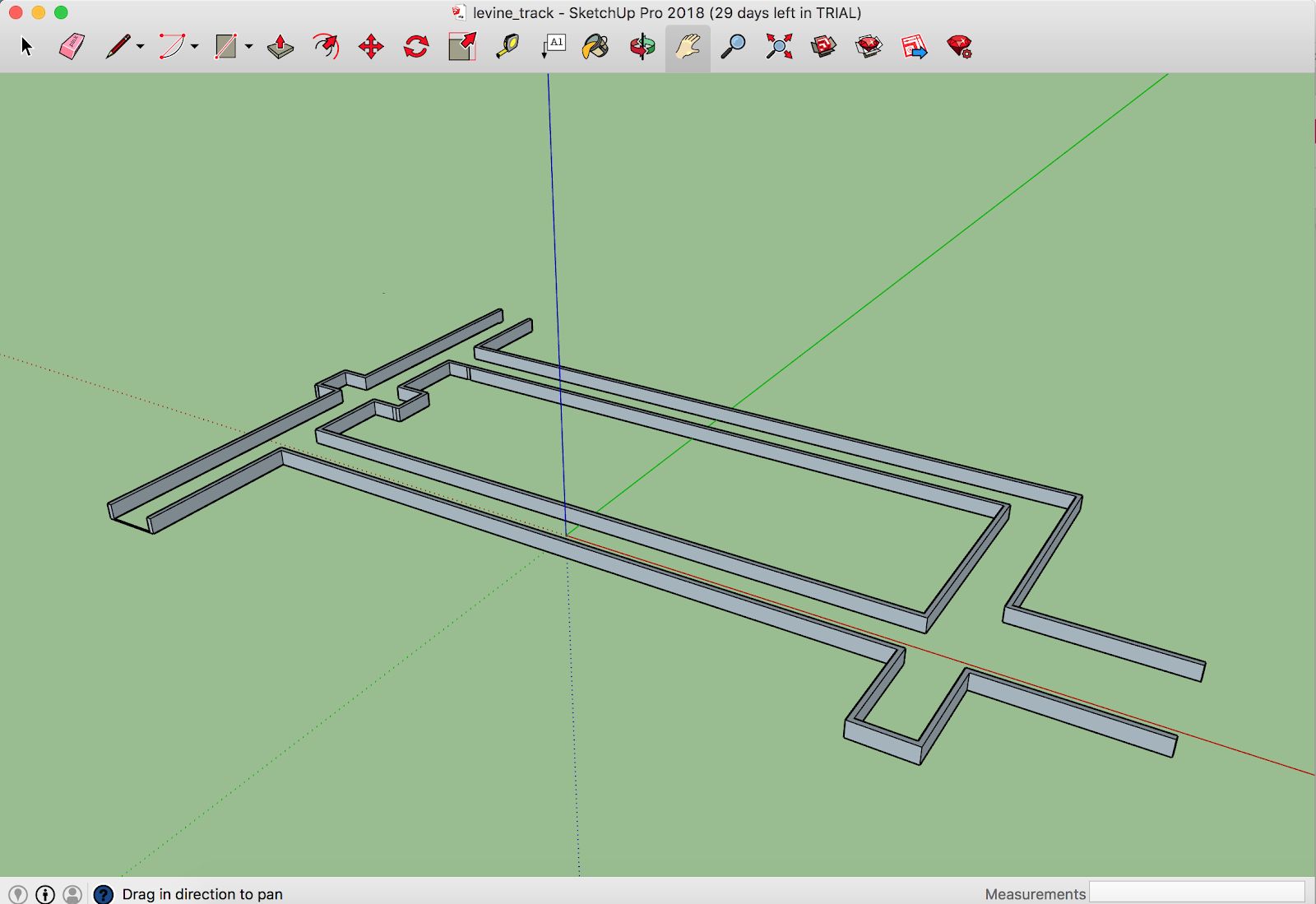

You should see a rectangular-shaped track, this is the Levine Building 2nd floor hallways outside of the mLab. The robot spawns at the origin and is doing a simple left wall follow. If you have a Logitech F710 joystick on hand and want to try controlling the robot with the joystick, you can do that by pressing the LB button on the top left while moving the joypads.

Want a Different Navigation Algorithm?

As the launch file name suggests, by default, the car runs Wall Following algorithm in the simulator. To change that, you need to edit the launch file. See the online references to understand ROS launch files.

Want a Different Track?

Other track files can be found in src/simulator/racecar-simulator/racecar_gazebo/worlds and have a .world extension.

To choose one of these tracks, open f110_ws/src/algorithms/wall_following/launch/wall_following.launch. Near the top of the file you will see

Change the value to the name of one of the track files, e.g.

Don’t Want the GUI?

If you are using the simulator to test some algorithms but don’t want to see the Gazebo GUI (because it’s heavy, or slow, or useless for now), you can disable it by editing the wall_following.launch file: in the <include .... racecar.launch> command, add this argument:

Moving the Car Manually in Simulation

Gazebo has a useful feature whereby you can move the car manually by clicking and dragging, thus over-riding whatever navigation algorithm it’s running. To translate the car, click on the crossing double-headed arrows on the top left of the simulation window (see below). Then grab the car with your pointer and move it. To rotate the car in place, click on the circular arrows; then grab the car and rotate it.

Creating a World

It can be really beneficial to create your own world. For instance, here in the mLab in Levine Building 2nd floor, it has been useful to create a .dae file that models that hallways to test our algorithms before taking the robot out into those exact hallways. We were able to obtain from the university architectural floor plans for the measurements, and also had to measure some things ourselves such as the inset of the office doors and the length of side hallways to elevator shafts.

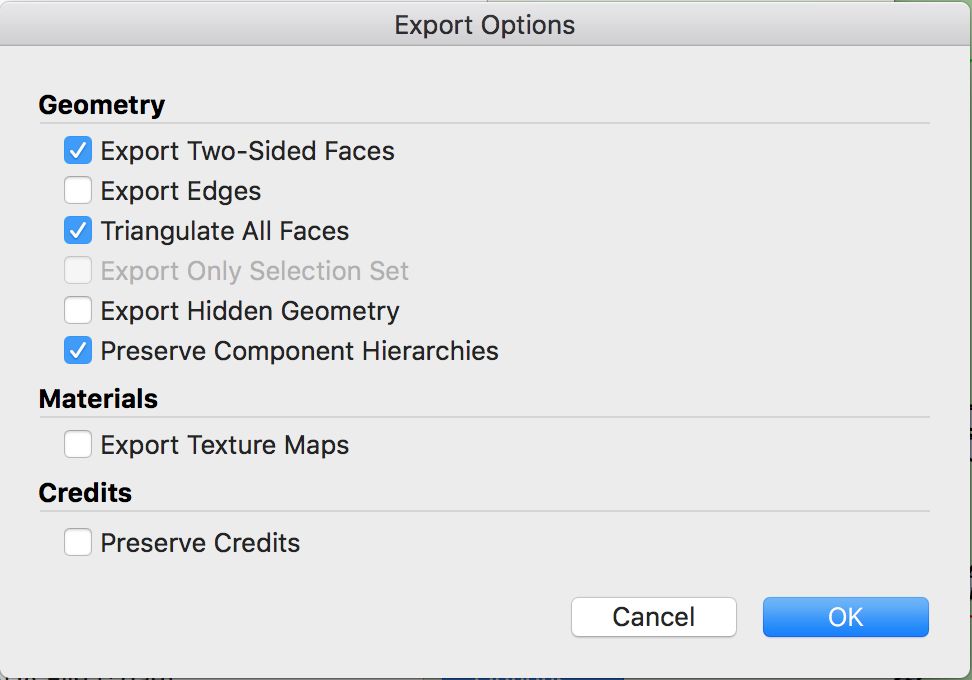

A .dae COLLADA file is a file used to represent surfaces. Note the emphasis on surfaces, whereas normal .obj files represent actual objects. We use Sketchup software because it is about as easy as it gets to create simple 3D models. If you want to try more advanced 3D modeling tools, feel free to try out software like 3DS Max, Solid Works, etc. In Google Sketchup, we draw rectangles to simulate the walls, and then pull them upwards to some height. Note that in Google Sketchup it is best to set the unit to meters since ROS does things in meters, not feet. Further note that we purposely did not create a ground in the world because Gazebo would treat it as collision physics and weird physics things occur. Instead, in our .world file in ROS, we will insert a Gazebo ground. Export your model with just the walls.

We had to experiment with different export settings for Sketchup. These are the checkboxes that worked best in Gazebo. The only 3 checked boxes are “Export Two-Sided Faces”, “Triangulate All Faces”, and “Preserve Component Hierarchies.” When we used different settings, such as including edges or hidden geometry, weird things would happen where the car would see invisible walls.

Once you’ve exported the .dae file, you will need to go into 3 folders in order to add the world.

- Navigate to f110_ws/src/simulator/racecar-simulator folders. You should then see folders “racecar_description” and “racecar_gazebo.” Inside racecar_gazebo/worlds create a new [track_name].world file. You can copy and paste another world to use as a template. Update all references to the new track name.

- Furthermore, inside of the racecar_description folder, you will need to update files within /meshes and /models. Inside racecar_description/models you will want to make a new folder with your track name (e.g. “levine_track”) with a model.config file and model.sdf file. If you copy and paste a template from an existing track, the steps will be pretty self explanatory in terms of updating the track names to your new track name.

- Inside racecar_description/meshes you will copy in your .dae file.

Now that you’ve created your .dae file with Sketchup and added it into the code, lastly you will want to update your launch file in order to use your new world. Follow instructions from the Gazebo Simulator section to update the launch file with your world name. Launch the world and you should see your world come up.

Algorithms

Wall Following

With our Hokuyo lidar sensor attached to the car, one of the simplest algorithms we can run is a wall following algorithm. The basic idea is that the car uses the lidar sensor to measure the distance to either the left wall, right wall, or both walls, and tries to maintain a certain distance from the wall. Inside the wall_following package under /launch you will see a file called wall_following.launch.

Run the following commands in terminal in order to see the robot do a simple left wall follow in Gazebo simulator.

$ source devel/setup.bash

$ roslaunch wall_following wall_following.launch

Now you should see the Gazebo simulator load with the car placed at the origin in our Levine Building 2nd floor world. The car tries to maintain a certain distance of 0.5 meters from the left all, and will continue following it around left turns in a counter-clockwise fashion. How is the code organized? From a high level view, data passes in this order:

The main code for the wall_following is under wall_following/scripts/pid_error.py. In this script you will find methods for followLeft, followRight, and followCenter. Pid_error.py subscribes to the laser scan /scan topic and calls the callback function each time it gets new lidar data (around 40 times per second). It uses PID to calculate the error and adjusts the steering angle accordingly in order to try to keep its desired trajectory a certain distance away from the wall. Pid_error.py then outputs over the /error topic a message type we custom defined called pid_input which contains pid_vel and pid_error. Control.py subscribes to the /error topic and limits the car’s turning angle to 30 degrees and slows down the car when it is making a turn, or speeds up the car when it is going straight. Control.py publishes to the /drive_parameters topic using our custom message type called drive_param which contains velocity and angle. Lastly, sim_connector.py subscribes to /drive_parameters and basically repackages the velocity and steering angle data into the AckermannDriveStamped message type so that it can be read in by the simulator under the /vesc/ackermann_cmd_mux/input/teleop topic.

If you run the Gazebo simulator long enough, you’ll notice that when the car reaches around ¾ of the way through the track, it encounter an opening on the left that leads to a dead-end. Because the car is programmed to just do a wall follow, it gets stuck here. How might we alleviate this problem? With hard-coded turn instructions, as described in the next section.

If you want to try running the wall following in the real world, run these instructions. Depending on how wide the hallway is that the car is driving in, you may want to modify the parameters for LEFT_DISTANCE and RIGHT_DISTANCE at the top of the pid_error.py file.

Wall Following with Explicit Instructions

If we do a simple wall follow (left, right, or center), the robot will always make turns at openings it sees. But sometimes we may not want the robot to turn into an opening because it dead ends, or we just want it to keep going down the hallway. The idea in this section is to give the robot a sequence of turn instructions, which it calls sequentially each time it sees an opening. For instance, imagine in the Levine World telling the robot to turn [“left”, “left”, “left”, “center”, “left”]. The “center” would allow it to skip the dead end opening and continue straight with a center wall follow instead. Explicit instructions also includes velocity instructions.

To run the hard-coded turn instructions code in the simulator, do the following in your terminal.

$ source devel/setup.bash $ roslaunch real_world_wall_following_explicit_instructions.Launch

To change the instructions, navigate to the explicit_instructions/instructions.csv file and change the values. You will see something that looks like this:

left, 2.0 left, 1.0 center, 0.5 left, 2.0 center, 1.5 stop, 0.0

The first value is the turn instruction and the second value is the velocity which gets executed after making that turn for some duration of time specified in the pid_error_explicit_instructions.py file.

The core logic is contained in the file wall_following/scripts/pid_error_explicit_instructions.py. There are a lot of comments in the code that describe the algorithm. At a high level, the car is constantly scanning for an opening by subscribing to the laser scan data. If the car detects an opening, then it takes the next instruction off of the turn instruction array and commits to that turn instruction for a specified number of seconds. The reason we commit for some seconds is that we don’t want the car to mistakenly think it sees a “new” opening midway through a turn, and prematurely call the next turn instruction.

How does the robot detect an opening? The robot scans to the right (and left as well) between some window of degrees. It compares lidar scans sequentially (so for instance, 0 degrees vs 0.25 degrees) and checks if the distance measured to 0 degrees and the distance measured to 0.25 degrees has a difference of some distance in meters. If there is a dropoff distance, then we know there is an opening.

A challenge we ran into is reflections off of metal plates on the doors in Levine Building. The robot calculated these as openings because Lidar data showed the points reflecting off the metal to be 60 meters away! Our solution was to ignore points that were further than 40 meters away because we know that they are metal.

You will also notice that in the real_world_wall_following_explicit_planning.launch file, we call a dead_mans_switch.py node. This allows us to use the joystick and the car only moves when the top right dead mans switch bumper is held down. This is for safety reasons.

If you notice your car is oscillating a lot on straightaways, try turning the kp value down in control.py.

Wall following with hard coded turns is a tedious algorithm because it requires us to manually predict where the car will detect openings before we launch the algorithm. Sometimes the car detects openings unpredictably, such as when it passes by an office with glass walls or when it goes down the ramp from Levine 3rd floor into Towne. This causes the car to prematurely take the next instruction set, which then interferes with the rest of the instruction sets. Hence we move on to localization and mapping next in search of a better solution to autonomous driving that doesn’t require as much human input and is more robust.

Gap-finding in LiDAR Scans [Houssam]

The topic on which lidar information messages are published is the /scan topic.If you run the simulator and run $rostopic info /scan, you will see the messages are of type std_msgs/LaserScan.

Scan Matching Odometry [Sheil]

ROS’ laser_scan_matcher package performs scan matching odometry.

Installing Packages

Getting the Example Launch File

The RoboRacer repo contains a launch file that demonstrates running the laser_scan_matcher on pre-recorded bag data. Copy it into your workspace’s src/ folder, e.g.

This folder defines a package, localization, which uses ROS’ laser_scan_matcher package.

Re-source your setup.bash, and you should be able to run

The majority of the parameters in the laser_scan_matcher node are taken from the ROS docs on the laser_scan_matcher package, available here.

In order to run the laser_scan_matcher on the pre-recorded bag file, execute the following lines in your terminal.

If you don’t want to see RViz, change the use_rviz arg in the launch file to “false”. The rostopic printing the pose of the car and covariance matrix is called /pose_with_covariance_stamped. You can read about it online.

Localization with Hector SLAM

We use Hector SLAM in order to generate a map given a bag file. First install hector-slam.

Run these following commands in order to reproduce it on your machine.

You will see an Rviz window open up that maps out the Moore Building 2nd floor loop. The launch file reads in a bag file which recorded all of the topics. Hector SLAM only needs the /scan topic (which contains the laser scans) in order to simultaneously map and localize. Note that no odometry data is used, whereas more advanced mapping packages such as Google Cartographer have the option to use odometry data and even IMU data.

Once the map is completely generated, in a new terminal window run the following in order to save the map as a yaml. The last string after “-f” is the name of the map you’d like to save. Since in this case we are using the Moore Building bag file, we appropriately name the map “moore”.

Now you will see in your home directory a levine.yaml file and a moore.pgm file. You will need both of these. We have already copied and pasted a version of this under localization/localization/maps/moore.yaml, as well as its corresponding moore.pgm file.

Now that you have Hector SLAM working, we can dive a bit more into the details of the hector_slam.launch file. At the top of the file you will see that we set the parameter /use_sim_time to true because the launch file plays a bag file. In this case, it’s a bag file recorded while the car did a single loop around Moore. Whenever we play bag files, it’s important to include the --clock argument because it causes ROS to play bag files with simulated time synchronized to the bag messages (more information here).

After the rosbag play instruction in the hector_slam.launch file, you will notice that there is a tf2_ros transform node that transforms between base_link to laser. This is very important to include or else Hector SLAM will not know where the laser is relative to the center of gravity of the car. In this case we use a static transform since the laser does not move relative to the car.

After the tf2_ros transform instruction in the launch file, you will see a reference to the hector_mapping mapping_default.launch file with parameters that specify the names of the base_frame, odom_frame, map_size, scan_topic, etc. Then there is a hector_geotiff which is used to save the map as a Geotiff file. Lastly, we launch rviz with a specific rviz_cfg (Rviz configuration) so that we don’t have to select all the topics we want to visualize every time weopen up Rviz. As a special note of interest, in algorithms below if you see in the launch file that there is a --delay of a few seconds added to Rviz, the reason is probably that we need to give Rviz time for certain nodes that generally take longer to publish to start publishing, otherwise Rviz will get old data.

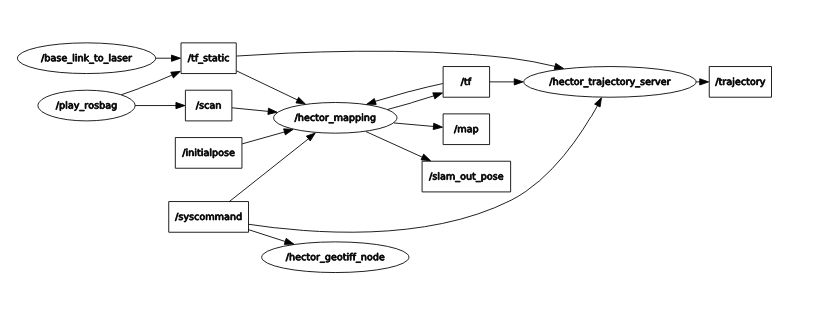

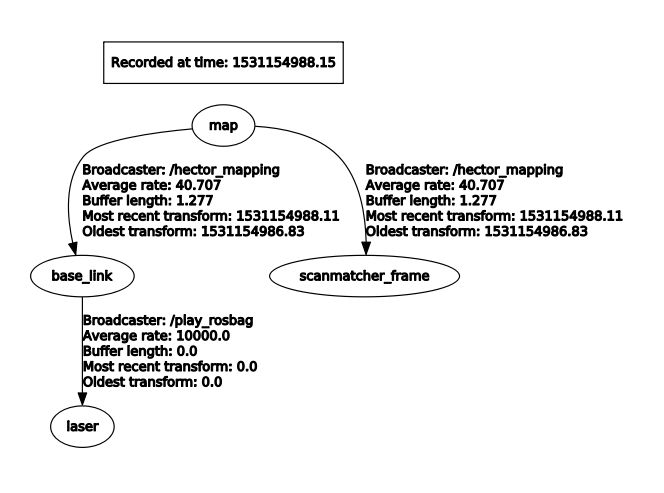

If your hector_slam.launch isn’t working correctly, a good way to debug is to compare your rqt_graph and rqt_tf_tree to the ones we have screenshotted below.

Rqt_graph for Hector SLAM generated by running “rosrun rqt_graph rqt_graph”

Rqt_tf_tree generated for Hector SLAM by running “rosrun rqt_tf_tree rqt_tf_tree”

Localization with AMCL (Adaptive Monte Carlo Localization)

Now that we have generated our map, the next step is to be able to localize the car within the map. Now you may ask, if we already did SLAM, then why don’t we use Hector SLAM to simultaneously localize and map each time this is run? The reason is that Hector SLAM is computationally intensive, and we don’t wish to generate a new map each time we run the car. Since we assume the world does not change (after all, walls do not break down very often), we only want to localize the car within the fixed world. In order to localize the car, we use an algorithm called AMCL (Adaptive Monte Carlo Localization).

First install amcl for ROS.

Next, run the launch file for amcl we have created. Note that we do not want roscore running because amcl will create its own ROS master. If we have two ROS masters there will probably be interference problems and hence AMCL will not run correctly.

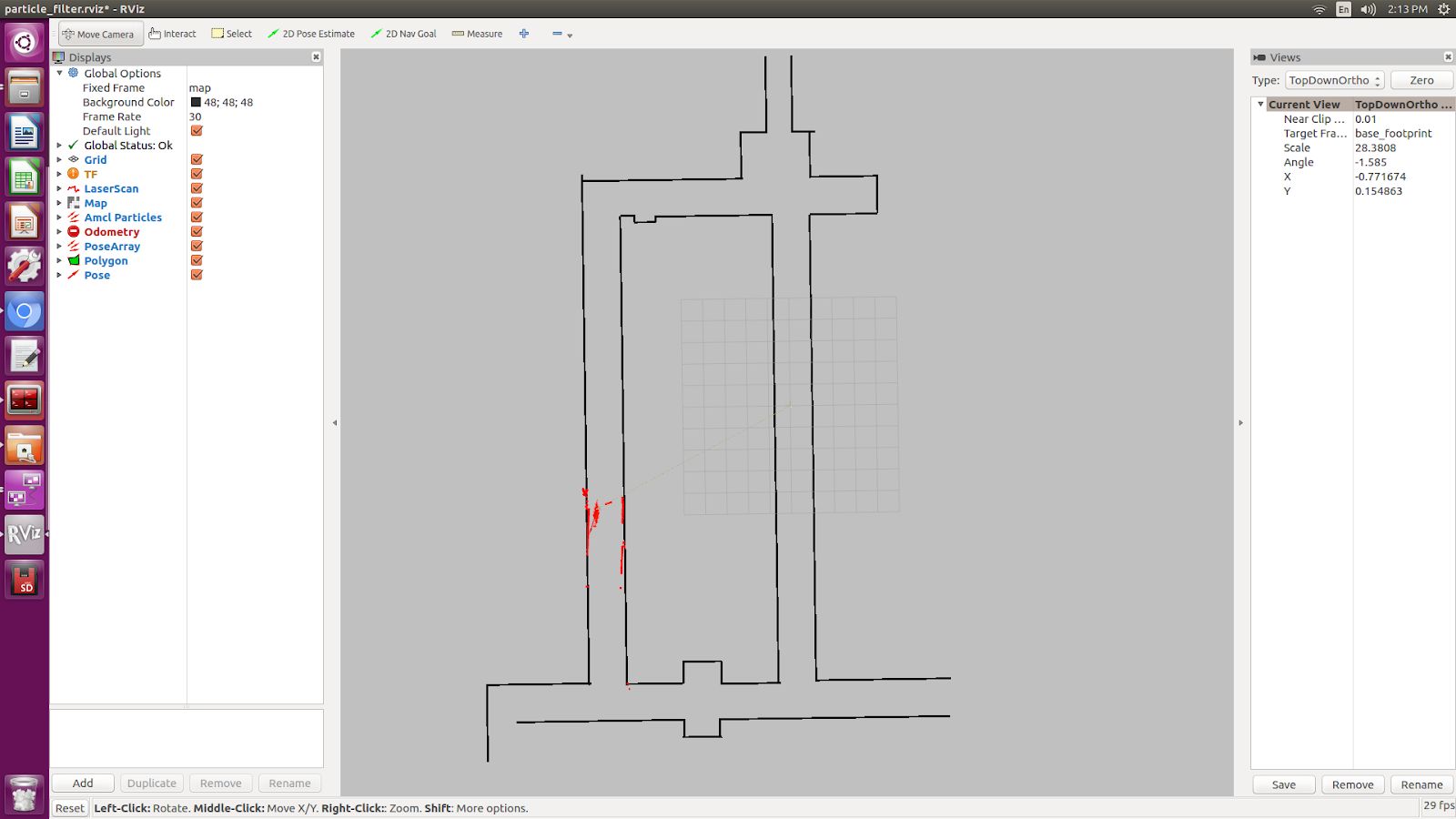

You should see Rviz open up after a delay of 5 seconds (which we purposely set in order to make sure everything is loaded, specifically the map server). Then, you will see the map appear and the car moving through the map with green particles around it. In Rviz, on the top center click on 2D Pose Estimate, then click and drag on where the car starts. It is important to set the initial pose because if we don’t then the car will start at the origin and its localization will be wrong. In the moore.yaml map, the car starts at the bottom center T-shaped crossroads, facing to the left. The car will do clockwise loop back to its original location.

Setting an initial 2D pose estimate for AMCL. Top bar, fourth button. Then click and drag in the map.

In the end, you should see a path that looks something like this image below. It won’t be perfect because AMCL requires a /tf (transform) topic. The best way we have to generate the /tf is to use the /vesc/odom topic, which literally counts the number of wheel spins and degree turns in order to estimate odometry. VESC odometry is not the most accurate because errors accumulate over time, but it gives a good general direction that guides AMCL with a general location for our car. We then used a messagetotf node in order to convert the /vesc/odom into /tf so that it can be used by AMCL.

Now that you have AMCL working successfully, time for some details on what’s going behind the scenes in the amcl.launch file. Like when we ran Hector SLAM, since we are playing this off of a bag file we need to set the /use_sim_time parameter to true. We also load a map_server node in order to publish the moore.yaml map. Note that we include the same base_link_to_laser transform as the one we provided Hector SLAM. After that line in the launch file is loading the amcl node, where we kept all the numerical parameters the same and only modified the base_frame_id and added initial pose x, y, and a. A is the orientation of the car relative to the map frame. You can read more on these in the AMCL page for information on each parameter.

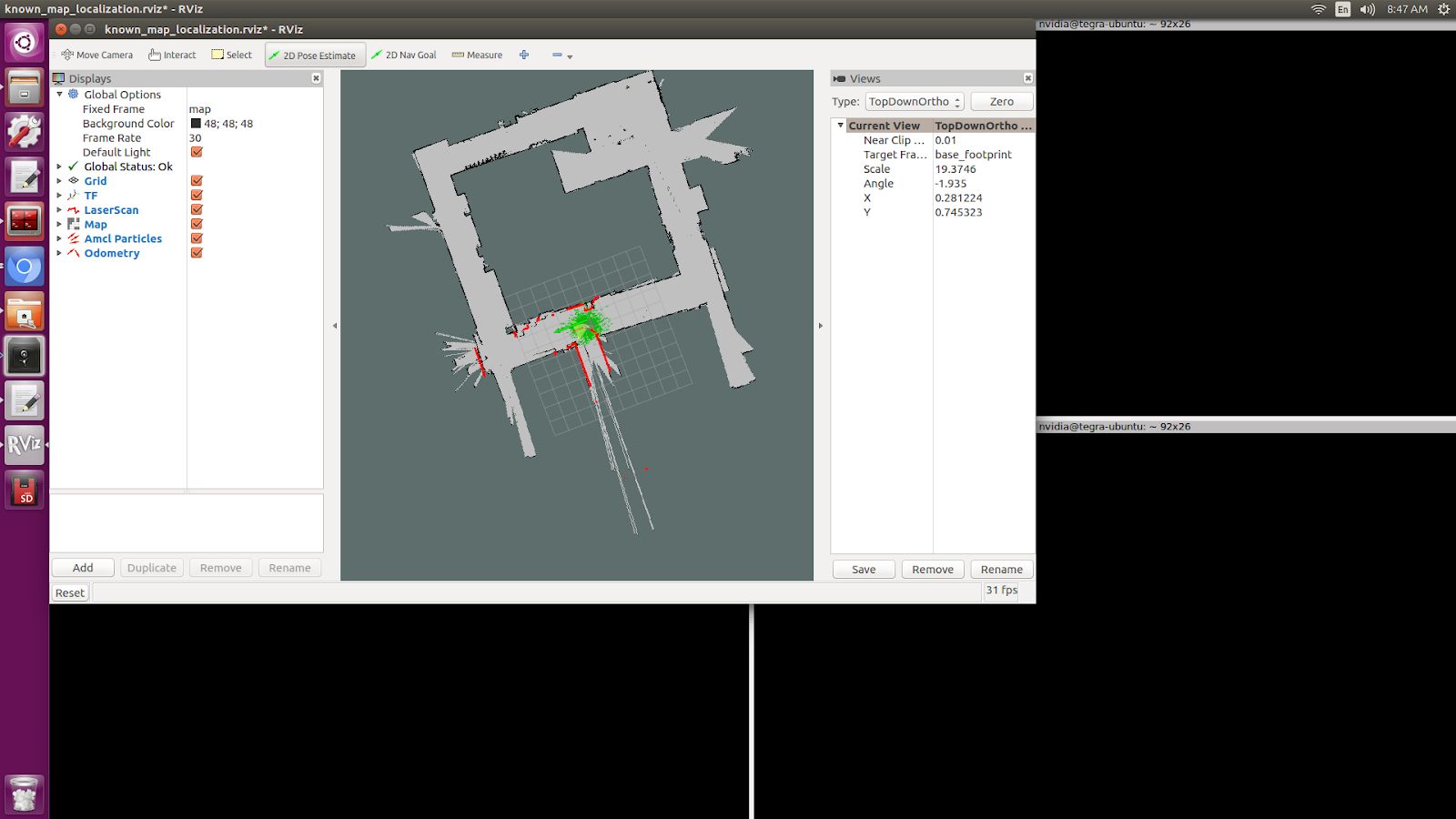

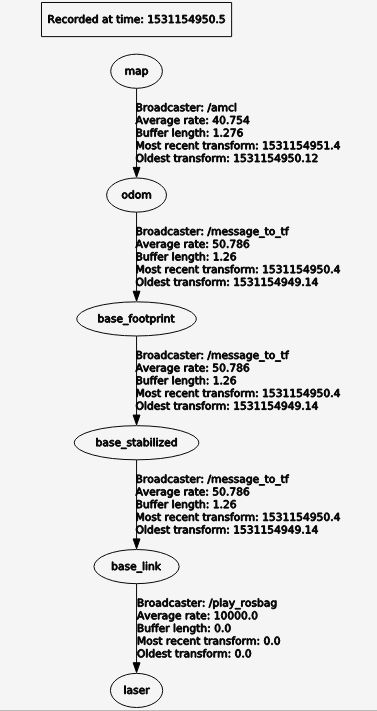

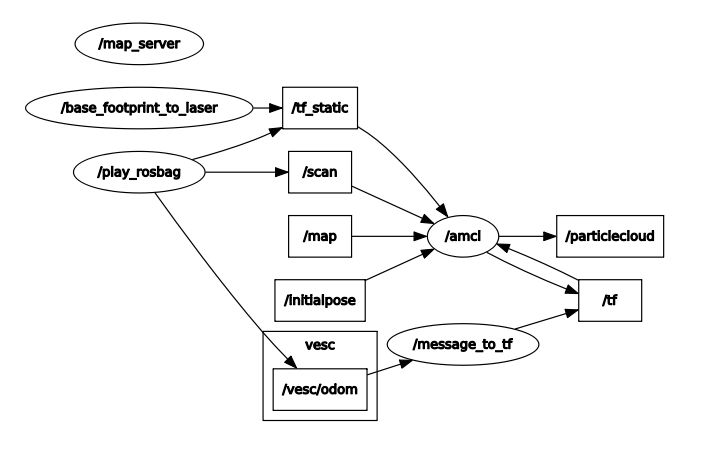

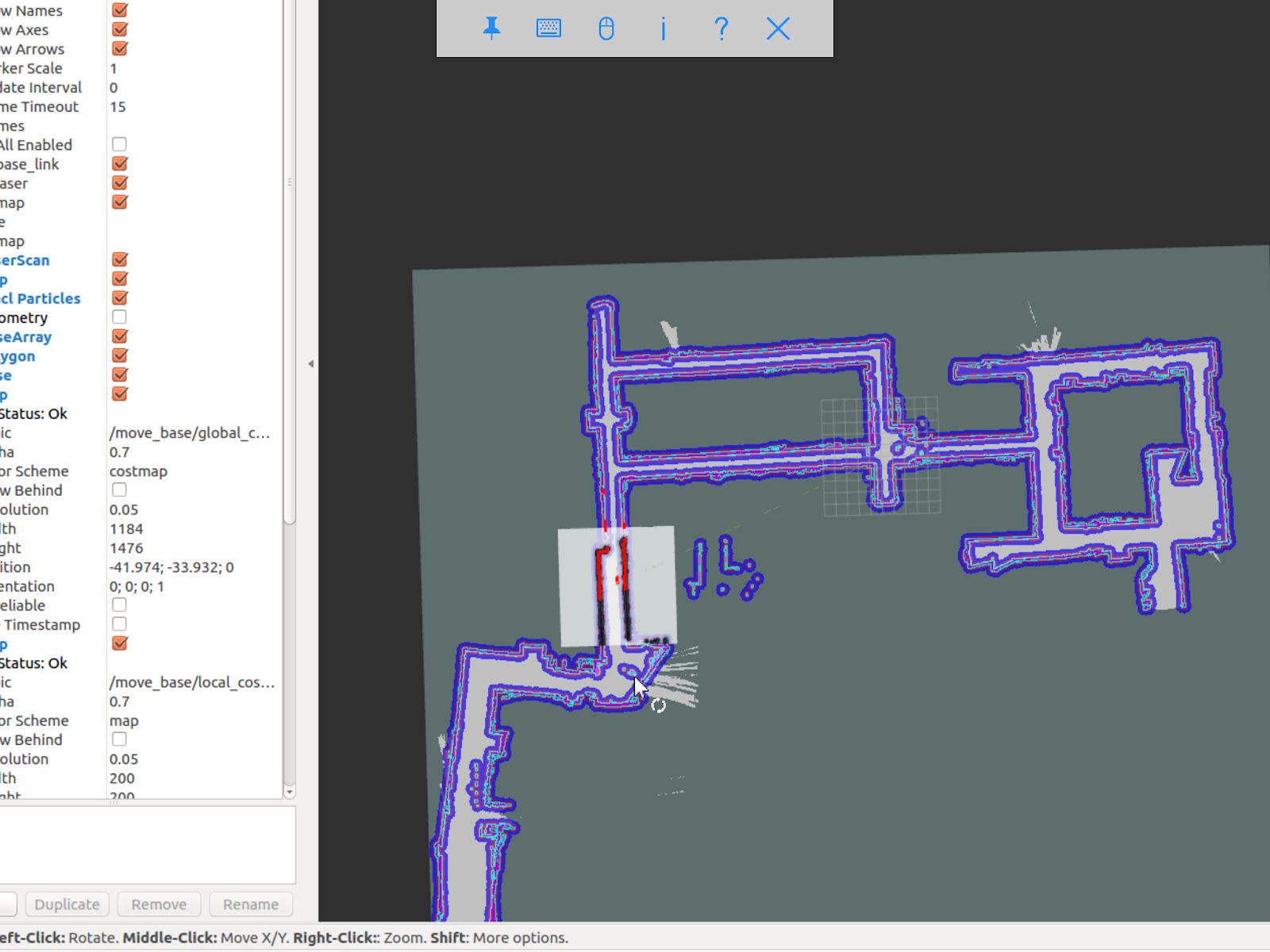

If your AMCL isn’t working, it’s a good idea to compare your rqt_graph and rqt_tf_tree to the ones we have included screenshots of below.

This is what the rqt_tf_tree looks like. You can verify if yours looks like this too by running rosrun rqt_tf_tree rqt_tf_tree in another terminal window while AMCL is running.

This is the rqt graph generated by running in a new terminal window rosrun rqt_graph rqt_graph.

Now that we can localize the car in a map, what’s next? Well, we can do really cool things! We can set waypoints for the car to follow, and those waypoints can have information not just about location but also speed at each point on the track. The car can use some type of pure pursuit algorithm in order to traverse from waypoint to waypoint. These will all be covered in the next sections.

Localization with Particle Filter (Faster and More Accurate than AMCL)

Why might you want to upgrade from AMCL to MIT particle filter? For one, AMCL only updates at around 4 times per second, whereas particle filter updates around 30 times per second. Additionally, particle filter uses the GPU whereas AMCL only uses the CPU. This results in the ability to use around 100x the number of particles, which results in more accuracy in localization. When we tried to use AMCL for localization with pure pursuit, we ran into challenges where we weren’t receiving any messages on the estimated pose topic because the car had not moved a certain threshold distance. When we set that threshold in AMCL parameters to be lower, the localization performance lagged. Hence we have been using the particle filter code written by Corey Walsh. The code follows this publication.

Follow instructions here to install RangeLibc and other dependencies for particle filter.

Once you have installed the dependencies, there is no need to install the source code because we have already included it inside of the /src/algorithms/particle_filter. To see a demo of the particle filter in action, navigate to the terminal and type in the following launch command.

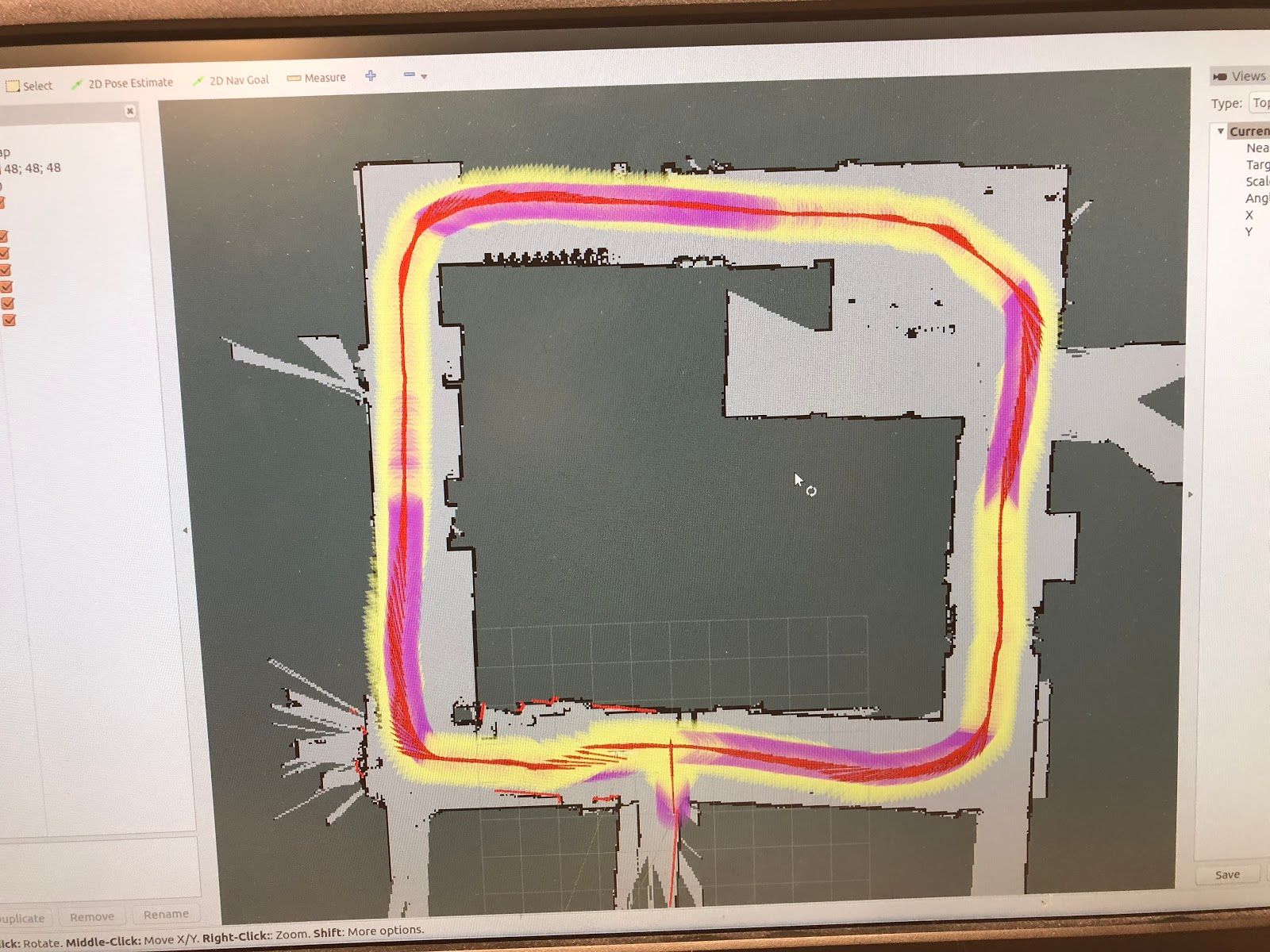

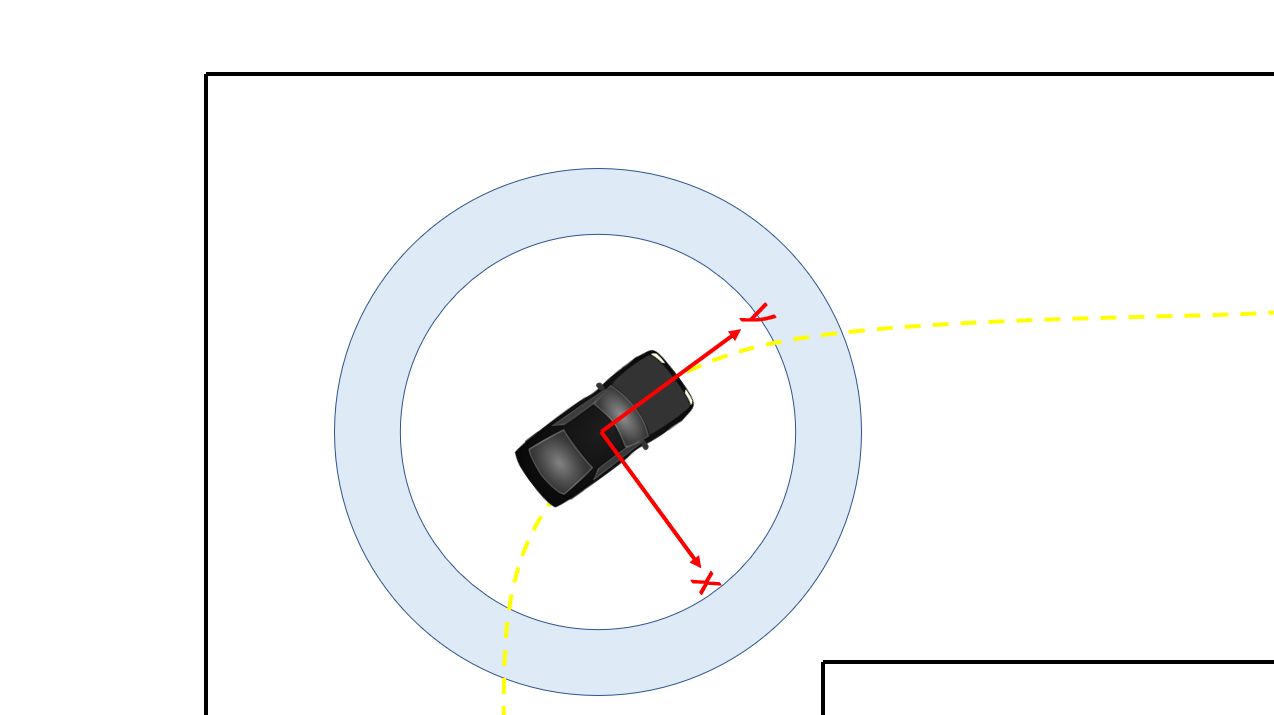

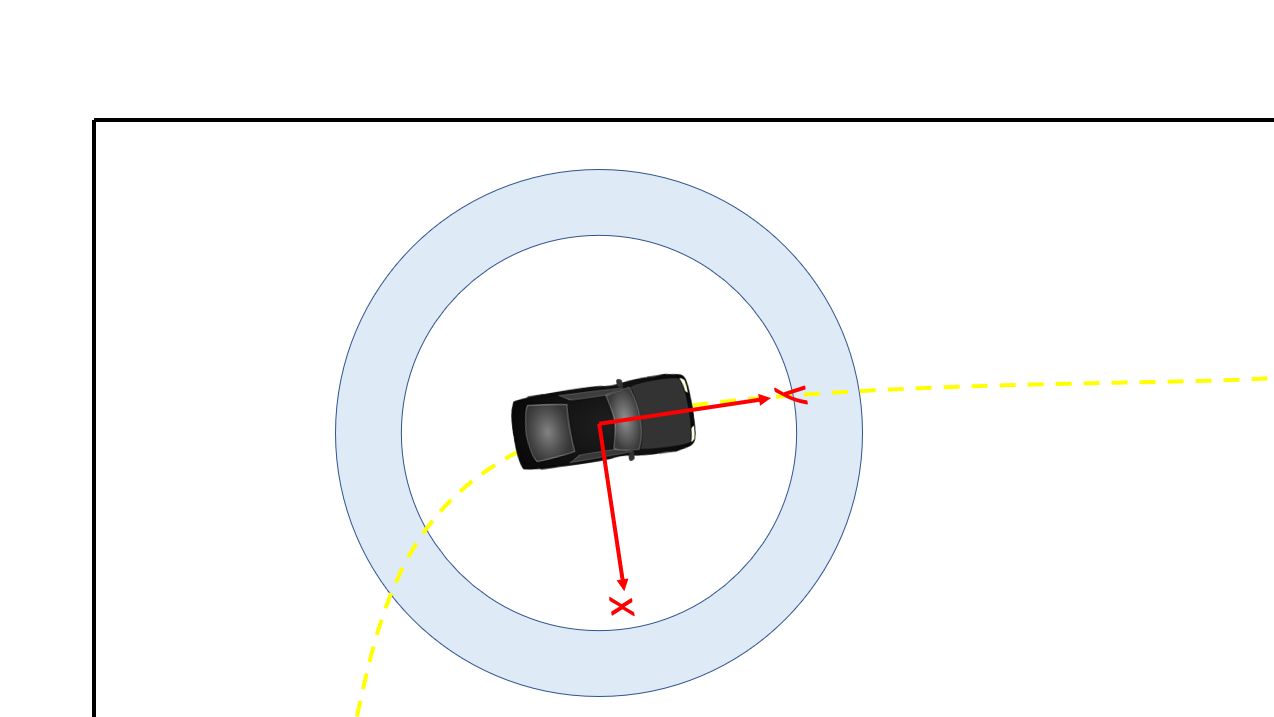

You can expect to see something like this:

An Rviz window opens up with a map and particles (in red), indicating where the car is in the world. The particle_filter.launch file is playing back a rosbag, so you should see the car and particles moving around the map in a counter-clockwise fashion. In the particle_filter.launch file we manually send a message to /initialpose topic but if you want to set it yourself in Rviz you can select the 2D Pose Estimate button on the top (4th button from the left) and click and drag in the map.

If you wanted to try it out in the real world with a joystick to see the localization live, you can run the particle_filter_live.launch file like this:

The difference between particle_filter_live.launch and particle_filter.launch is particle_filter_live.launch doesn’t play a rosbag, doesn’t use simulated time, and instead includes the teleop.launch file. Everything else is the same.

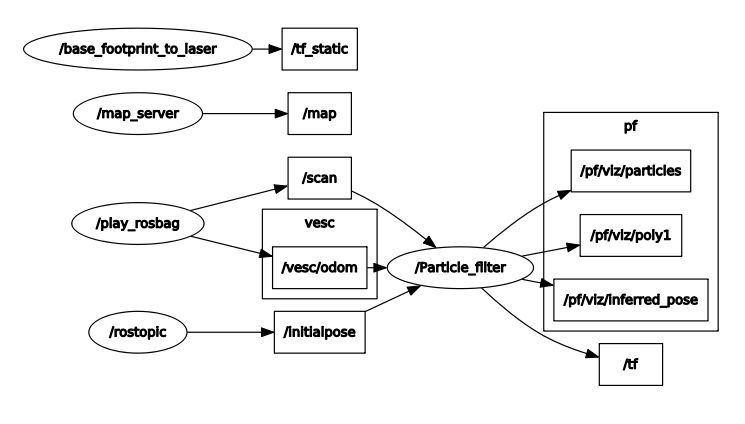

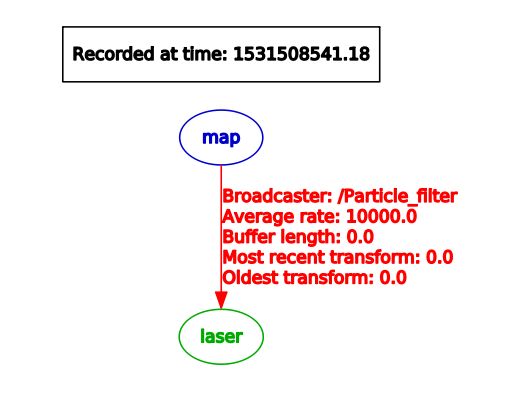

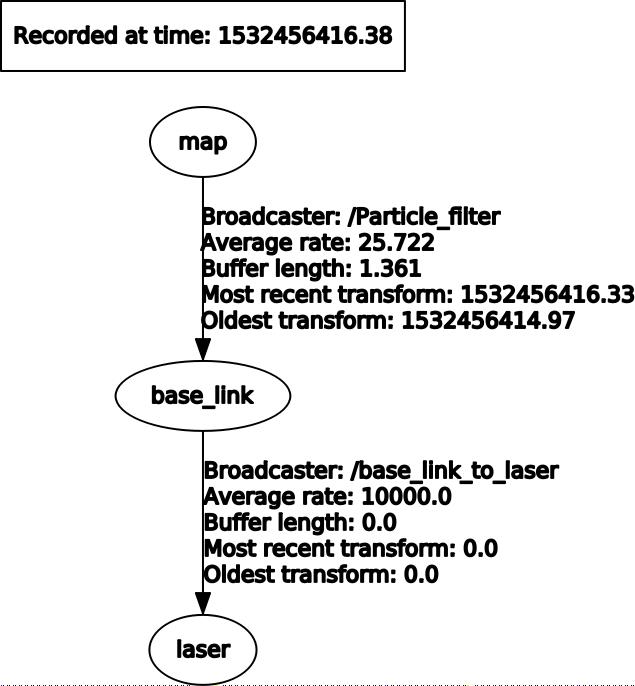

Now that you have the particle_filter.launch working, let’s examine the contents of the file more carefully. You will notice many overlaps between particle_filter.launch and amcl.launch and hector_slam.launch. For instance, you will recognize the map server, the /use_sim_time parameter, the rosbag and the static transform between base_footprint to laser. Note that in particle_filter.launch we use the name base_footprint instead of base_link because particle filter calls it the base_footprint. Then we load the particle_filter node with a few arguments. We tell particle_filter that our scan_topic is called /scan and that our odometry topic is called /vesc/odom. We keep the max_particles of 4,000 at the default number. Below are screenshots of the rqt_tf_tree and rqt_graph.

What if we want to run particle filter with a slower update rate? (In order to appreciate the speed that the GPU offers or to simulate on a slower computer). Inside the particle_filter.launch file, you can change the “range_method” from “rmgpu” to “bl”. As documented on the particle filter Github repo, “bl” does not use the GPU and has much less particles. Our testing shows that “bl” achieves an inferred_pose update rate of around 7Hz, whereas “rmgpu” achieves 40Hz.

Rqt_graph for particle filter

Rqt_tf_tree for particle filter

Generating Waypoints

Now that we have localization down, the next step is to be able to follow a set of waypoints. The waypoints are (x, y) coordinates with respect to the map frame. We can expect around 2,000 - 4,000 waypoints for a loop of length around 66 meters.

Do the following to save waypoints.

# Allow the car to be controlled with joystick

$ roslaunch racecar teleop.launch

# Record a rosbag with just the scan and vesc/odom topics. Will be saved

into your Home directory. (In a new terminal window)

$ rosbag record scan vesc/odom

# You will need to modify particle_filter.launch with path to rosbag you

just recorded

$ roslaunch localization particle_filter.launch

# Records waypoints and saves as waypoints.csv in current working directory

$ rosrun waypoint_logger waypoint_logger.py

At this point, in your current working directory you will see a csv file called waypoints.csv. Let’s go into further detail on what is going behind the scenes. Particle_filter.launch plays the rosbag that you recorded (of course, you have to update the particle_filter.launch with the path to your bag file you recorded). The particle filter subscribes to the vesc/odom and scan topics, and it outputs a stream of messages over the topic pf/viz/inferred_pose. Waypoint<_logger.py subscribes to pf/viz/inferred_pose and saves the x, y coordinates in each callback to a CSV file.

Now that you have your waypoints.csv file, the next step will be to use this list of waypoints and have the car follow them using pure pursuit.

Following Waypoints with Pure Pursuit

Now this is the really exciting part.

Before you run the pure_pursuit.launch file, you will need to change the path to the map you would like loaded in pure_pursuit.launch. Additionally, you can also set the initial position of the car in the map frame. That way, you don’t need to manually draw it out each time in Rviz. By default we will set a map and initial pose so that you can see the pure pursuit running.

Additionally, inside of pure_pursuits.py, you will need to update the path to the waypoints file that you would like to use. In pure_pursuits.py you can also set a velocity. We recommend starting with something slow like 0.5 m/s with a lookahead distance of 1.5 meters.

Now you are ready to run the launch command to start the car moving.

To run in the simulator (recommended to do this first):

Note that the Gazebo simulator works well with pure pursuit algorithm only at slower speeds, around 1 m/s on turns and less than 4 m/s on straightaways. The reason is that on turns with higher speeds than 1 m/s, Gazebo models the car as sliding out more with a much larger turn radius. We’ve tried a dozen ways to try to fix this overestimation of turning drift, but with no success. Hence we use Gazebo mainly to test that algorithms work at slower speeds, then take the car into real world to slowly ramp up the speed.